Now that Democrats have taken control of the House of Representatives, some lawmakers are looking for ways to rewrite the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. There are opportunities to improve the law but also pitfalls that could make it worse. In a series of three blogs, the Tax Policy Center’s Robert McClelland looks at some potential reforms. This one looks at partially or fully restoring personal exemptions.

Temporarily eliminating the personal exemption was one of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act’s (TCJA) most significant changes to the tax code. Although the personal exemption had been a mainstay of the modern income tax since its beginnings, eliminating it—even only through the end of 2025— raised substantial revenues. The personal exemption excluded a base amount of income from tax for each person in the taxpayer’s household, reducing taxes for most households and eliminating the tax burden of many low-income families, even those without children.

Maintaining good tax policy principles while restoring the exemption is not easy. To start, by reducing the exemption amount to zero, the TCJA generated almost $1.2 trillion in new revenue over 10 years—money that was used to pay for other provisions that cut taxes for most households. For example, over that time period increasing the standard deduction will reduce revenue by $720 billion, increasing the child tax credit will reduce revenue by $573 billion and lowering individual income tax rates will reduce revenue by $1.2 trillion. The challenge is to find a way to bring back the exemption without raising taxes for low- and moderate-income households, reducing incentives to work, and without adding to the deficit.

Accomplishing all three goals simultaneously is nearly impossible. But there are some ways to restore the personal exemption while accomplishing at least a portion of these goals. Here are a few examples:

Restore the personal exemption and raise tax rates. Ending the personal exemption generated almost the same amount of revenue that the individual tax rate cuts cost. What would happen if Congress restored both the personal exemption and the pre-TCJA individual income tax rates? The TCJA’s rate cuts combined with ending the personal exemption benefitted the highest income 20 percent of households, partially at the expense of those with lower incomes. The rate cut also increased the marginal incentive to earn income for most taxpayers. So, restoring these provisions to pre-TCJA law would benefit the bottom four quintiles at the expense of taxpayers in the top quintile, but it also would increase marginal income tax rates and thereby reduce the incentive for most taxpayers to earn income.

Restore the personal exemption but reduce the standard deduction and the Child Tax Credit (CTC). The TCJA raised the standard deduction and CTC, together reducing revenues by about the same amount raised by eliminating the personal exemption. Raising the standard deduction and the CTC also offset the loss of the personal exemption for many taxpayers.

But not everyone was made whole by those changes. Dependents older than 16 cannot be claimed for the child tax credit (although they can be claimed for the generally less valuable $500 dependent tax credit.) In addition, taxpayers lost the exemption for themselves and their spouses entirely; for some, that loss was offset by the increase in the standard deduction but that did not benefit those who continue to itemize.

Restoring the personal exemption, the standard deduction, and the CTC to their former levels would hurt lower-income filers more than higher-income filers. The personal exemption generally lowered taxes of high-income taxpayers, who had higher marginal income tax rates, more than those with low-incomes (even though pre-TCJA law phased out the personal exemption for high-income taxpayers).

The CTC, on the other hand, reduces taxes of all taxpayers with incomes below its phase-out range by up to $2,000 and is partially refundable. Similarly, raising the standard deduction does not help those typically higher-income taxpayers who still itemize. Therefore, eliminating the personal exemption and increasing both the standard deduction and the CTC generally benefits lower-income tax filers more than those with higher incomes. Restoring the personal exemption, the standard deduction, and the CTC to pre-TCJA levels would do the opposite; it would cut after-tax incomes for lower-income filers.

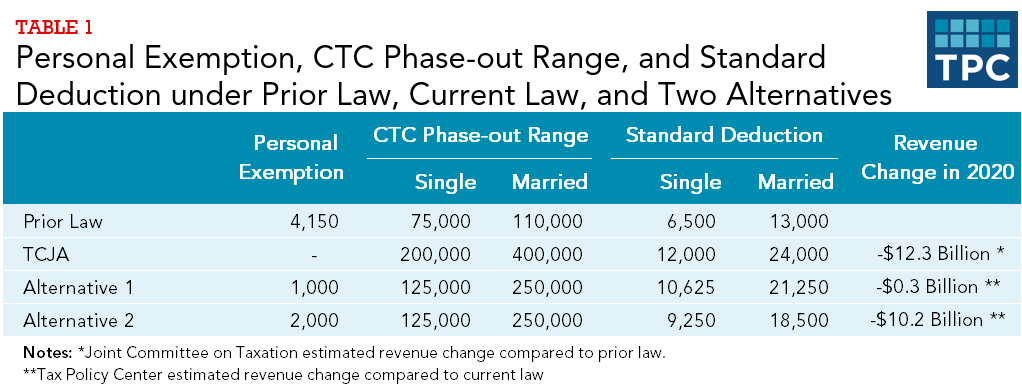

Partially restore the personal exemption and reduce the standard deduction and the phase-out threshold of the Child Tax Credit. Previously, the standard deduction was $6,500 for single filers and $13,000 for married filers. The TCJA raised those deduction amounts to $12,000 and $24,000, respectively. At the same time, the TCJA increased the beginning of the phase-out range for the CTC from $75,000 to $200,000 for single filers and from $110,000 to $400,000 for married taxpayers filing jointly. Congress could set a new limit between the old and new levels, and the resulting revenue could fund a partial restoration of the personal exemption.

Two possible alternatives are shown in Table 1. In the first, the personal exemption is set to $1,000 at the cost of about $0.3 billion in 2020. In the second example, the personal exemption is raised to $2,000 at the cost of about $10 billion in 2020. In both cases, the beginning of the CTC phase-out range and the value of the standard deduction are greater than under prior law.

It is tempting to restore the personal exemption but Congress need to be careful of the cost, the distributional effects, and its effect on incentives to work.