On the California ballot this year is an initiative that could partially unravel what is possibly one of the most consequential ballot initiatives in the state’s—if not the nation’s—history.

Just over 40 years ago, Californians resoundingly approved Proposition 13, which limited the ability of local governments to tax property in California and helped trigger a “tax revolt” across the country.

If approved, Proposition 15 would undo some of those limits and significantly increase taxes on many commercial and industrial properties in the state. Proposition 15 might not shift the trajectory of tax policy for a generation, but it could significantly reshape California’s finances.

Proponents of Proposition 15 argue it would achieve two major fiscal goals: rebalance the state’s revenue mix and improve public services, such as education and infrastructure by adding between $6.5 billion to $11.5 billion in annual tax revenue when the measure is fully implemented.

Opponents argue the initiative will discourage business investment in California and claim that the timing of the tax increase could not be worse given the ongoing pandemic and recession.

To better understand these arguments, it’s important to understand what California’s revenues and spending look like and how Prop 15 might change things.

Proposition 13 vs. Proposition 15

Proposition 13 restricted property taxes in California in two ways: it limited tax rates to 1 percent of assessed value and changed how properties are assessed. Proposition 15 targets the latter.

Currently, the assessed value of a property in California is set at its purchase price, not its market value, and annual assessment increases are limited to 2 percent or the rate of inflation (whichever is lower). The assessed value of a property resets to market value only when the property is sold. As a result, two neighboring properties with the same market value could have radically different tax assessments and tax bills if one was last sold in the 1970s and the other in the 2010s.

Proposition 15 proposes assessing and taxing commercial and industrial properties (valued at more than $3 million) at market value, which would cause property taxes to rise for many owners of those properties.

The ballot measure would not change how residential and agricultural property is taxed. Thus, some say it would “split the roll” by allowing different rules for different property types. This ”split roll” approach is common, as 24 states and the District of Columbia have similar systems.

What California’s Finances Look Like 40 Years After Prop 13

Proposition 13 dramatically changed how California funds its governments. Most states aim for a balanced “three-legged stool” of property, income, and sales tax revenue, but over the past 40 years California has become increasingly dependent on income tax revenue.

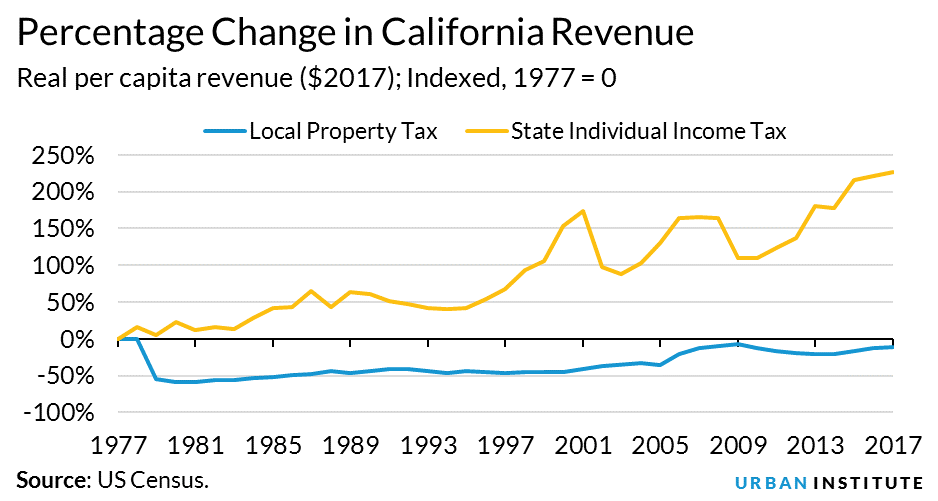

In 1977, 28 percent of California’s combined state and local general revenue came from property taxes—well above the average across all states. By 2017, that share had fallen to 14 percent—well below the national average. Over the same period, the share of state and local general revenue from individual income taxes rose from 10 percent (average) to 19 percent (well above average).

Relying on income taxes isn’t necessarily bad. Notably, income taxes are more progressive than property taxes. But income tax collections rise and fall with economic conditions. An overreliance on income taxes makes it difficult for governments to balance budgets during economic downturns.

In contrast, property tax revenue tends to be far more stable over time. Public finance economists advocate for a mix of revenue because when these taxes work together they can achieve both stability and equity.

What Prop 15 Could Mean for California’s Future

The additional and more stable property tax revenue could enable California to make needed improvements to its educational system and infrastructure.

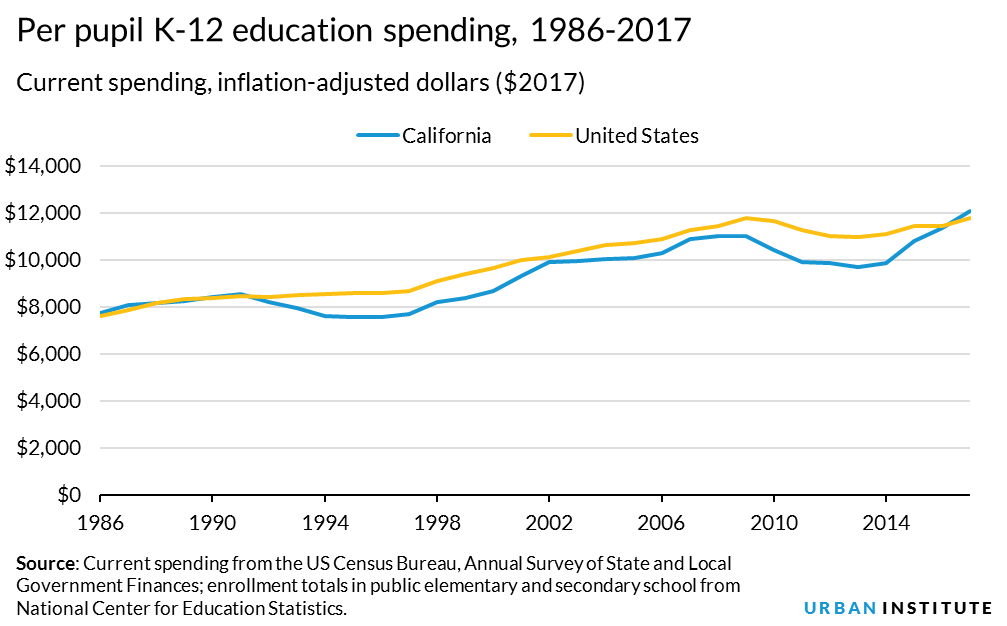

California’s per pupil K-12 education funding often tracks the national average, but it notably falls below average levels during economic downturns. This is in part because the state is so reliant on volatile income tax revenue.

Further, even when California’s K-12 funding is on par with the national averages, the state is still possibly underfunding education. Compared to other states, California’s student body is more diverse and includes more English-language learners and students living in poverty, groups of students who have been shown to need additional revenue to receive an adequate level of support. Thus, to adequately prepare all its students, the state likely needs to spend relatively more per capita than many other states.

California’s infrastructure spending is also often in line with national averages, but that may be similarly inadequate given the state’s specific needs and its backlog of deferred maintenance.

California faces mounting infrastructure challenges from population growth (especially in previously underserved areas) and global climate change, which has caused extreme heat, drought, poor air quality, and a rise in sea levels. A volatile revenue system makes it difficult to plan long-term infrastructure projects, which require a steady and reliable flow of resources to support construction and maintenance of these assets.

California’s Choice

While the current economic downturn is obviously at the forefront of everyone’s mind, Proposition 15 would not provide an immediate infusion of revenues (or tax hikes) as the first reassessments would not occur until 2023. Regardless of what voters decide, the state will still have to make tough budget decisions over the next few years, especially if there is not more federal assistance for states.

But California voters will get to decide this year what important parts of their future tax system look like. Will Californians make higher taxes on commercial property part of the long-term solution to its fiscal challenges? Or will Proposition 13 remain California’s defining tax law?