Democrats started this year with President Biden’s proposal to raise taxes on high-income households as a way to help pay for an ambitious social spending agenda. Then they took an odd turn: They still seem to want to tax the really rich, though by much less than Biden did. But they also are looking to protect, or even benefit, the merely rich.

The vehicle for these changes, the House version of Biden’s Build Back Better social spending, climate, and tax bill, is now in legislative limbo following Sen. Joe Manchin’s (D-WV) declared opposition. But since some new version is likely to surface early next year, it is instructive to look at the evolution of its tax provisions so far.

Biden himself set the stage for this turn of events during his presidential campaign, when he declared that he would not raise taxes on anyone making $400,000 or less. For context: $400,000 is nowhere close to middle income. Less than 5 percent of households make that much. And $400,000 is roughly six times the median household income in the US.

The $400,000 red line

That $400,000 rule became a red line that neither Biden nor congressional Democrats have been willing to cross. In his campaign, the president proposed raising the top individual income tax rate, limiting the value of itemized deductions, imposing new Social Security payroll taxes, and raising taxes for owners of pass-through businesses—but only on those making more than about $400,000.

He also proposed raising the capital gains tax but only for those making $1 million or more, lowering the estate tax exemption to $3.5 million and taxing at death unrealized capital gains of more than $1 million.

That $400,000 rule itself meant that many high-income and wealthy households—at least by the standards of most Americans—were protected from higher taxes. Still, for those making more than $400,000 or those with substantial assets, Biden was proposing hefty tax increases.

The attrition began with Biden’s Fiscal 2022 budget when he dropped the Social Security and pass-through tax changes.

Congress at work

Then Congress got ahold of Build Back Better.

The House Ways & Means Committee kept a version of the top individual income tax rate hike, increased capital gains tax rates (though by less than Biden proposed) and added a surtax on incomes of $5 million and up. But it scrapped Biden’s proposals to tax unrealized gains at death and toughen the estate tax.

Then, in an effort to satisfy concerns of a handful of Senate Democrats, the full House made more revisions. It scrapped or shifted up the income scale many of Biden’s tax hikes.

The House dumped the individual income tax rate hike in favor of an income tax surcharge on those making $10 million or more. It dropped the capital gains tax increases entirely. And then it added a provision to raise the state and local tax (SALT) deduction cap from $10,000 to $80,000. That piece largely would benefit those making between about $365,000 and $870,000—those in the highest 95th to 99th income percentiles. The top 1 percent also would be big winners. But the very rich, the top 0.1 percent, would get a—for them—very modest benefit.

A changing picture

As the size of the overall tax increase shrinks, all high-income groups would pay less than Biden originally proposed. But these revisions also dramatically changed the way the tax plan affects people with high and higher incomes.

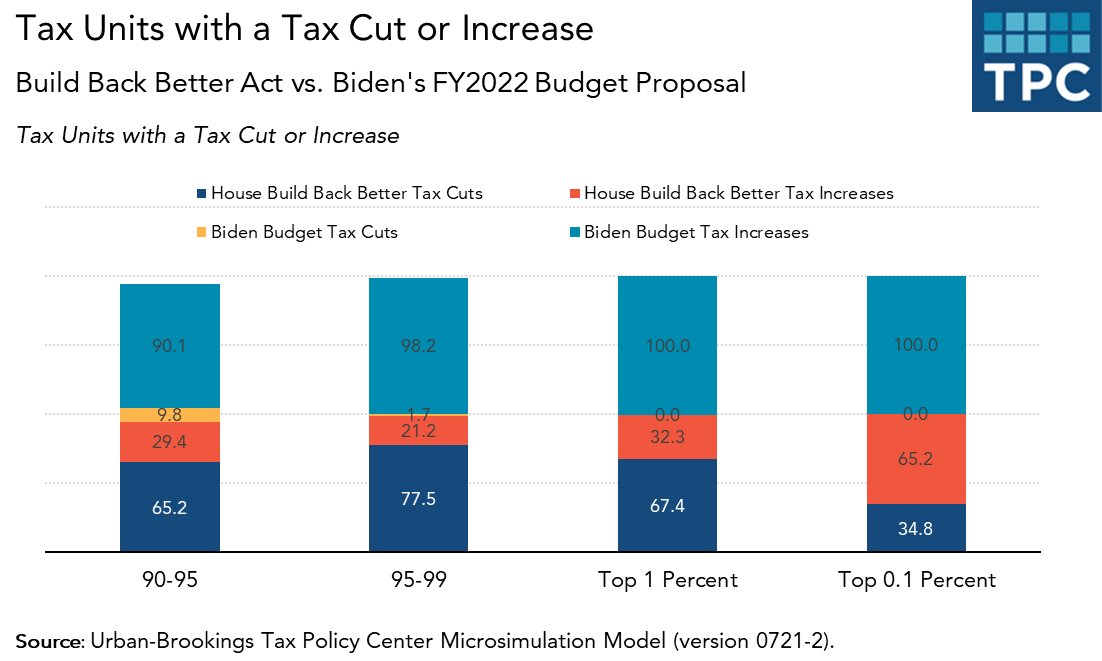

TPC estimated that in 2022 Biden’s Fiscal 2022 budget proposal would have raised taxes on about 98 percent of people in the 95th to 99th percentile. We’ll call them the merely rich. On average, they would have paid about $5,000 more in taxes than under current law. And their after-tax incomes would have been cut by about 1.3 percent.

By the time the House finished with the bill, the picture changed considerably. Under its version of BBB only about 20 percent of those in that 95 to 99th percentile would pay more in taxes, about $1,800 on average. And three-quarters would get a tax cut, averaging about $6,000. Overall, their after-tax incomes would rise by 1.1 percent.

Now, let’s look at the really rich—those in the top 0.1 percent (who will make $3.5 million or more in 2022). Effectively all of them would have paid more under Biden’s budget plan. Their average tax increase would have been about $1.6 million or nearly 17 percent of their after-tax income.

Under the House bill only about two-thirds of those in the top 0.1 percent would pay more in taxes. And about one-third would get a tax cut. On average, the top 0.1 percent would pay about $585,000 more in taxes than under current law, one third of what they would have paid under Biden’s budget plan. Their after-tax incomes would fall by about 6 percent.

It remains to be seen what will happen next. But so far, at least, Congress is not only shrinking Biden’s high-income tax hikes, it is shifting them away from the merely wealthy. Tax changes that largely benefit households with annual incomes from $370,000 to $870,000 may help big campaign contributors but they don’t do much for ordinary voters.