Several changes in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) significantly reduce the tax benefits of taking out a home mortgage (though these changes are scheduled to reverse after 2025). Will the increase in the after-tax cost of mortgage interest encourage some homeowners to use financial assets to pay down their mortgage debt? In at least some cases, the answer is yes.

Most homeowners take out mortgage loans because they don’t have the financial assets to purchase a house outright. But others may benefit from borrowing for purposes other than a home purchase. Imagine a very high net worth individual who wants to buy a $1 million home. She easily could afford to pay cash for the home. But she might choose instead to make a down payment of only $200,000 and invest the extra $800,000 in a diversified portfolio of stocks and bonds.

Now imagine the after-tax rate of return from her investments is 3.5 percent, her 30-year home mortgage interest rate is 4 percent, and her marginal tax rate is 30 percent (this example assumes a simple income tax system with the same rate applying to both portfolio income and itemized deductions). Her mortgage interest rate (after the mortgage interest deduction) is only 2.8 percent (4 percent*(1-30 percent)), which is lower than her after-tax investment return. Thus, she may be better off taking out a larger mortgage and investing the extra money, after accounting for any increased riskiness of her portfolio.

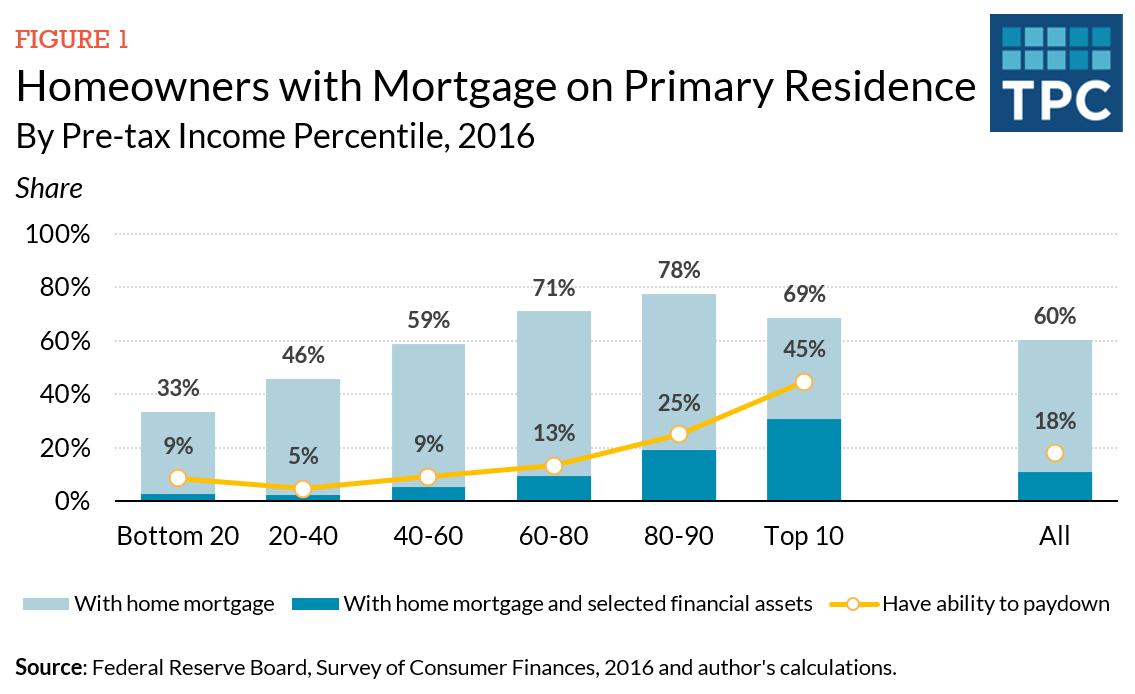

Federal Reserve data show that in 2016, about three-fifths of homeowners had a mortgage on a primary residence (Figure 1). The share of homeowners with a mortgage increased with income, except for those with the highest incomes. Similarly, the share of households holding both a home mortgage and other financial assets, such as bonds and stocks, also increased with income.

Homeowners are responsive to tax law changes that limit the mortgage interest deduction (MID). For example, the TCJA reduced from $1 million to $750,000 the size of mortgage loans on which taxpayers can deduct interest. My Tax Policy Center colleagues Robert McClelland and Safia Sayed showed that a significant number of new homeowners took out smaller loans in response to the reduced cap.

Tax law changes that affect the net cost of borrowing also can trigger homeowners to rebalance their asset holdings. By raising the standard deduction and capping the state and local tax deduction, the TCJA substantially reduced the number of taxpayers claiming itemized deductions. Those taxpayers who switched from itemizing to taking the standard deduction lost the tax incentive to mortgage finance their home purchases. Absent the MID, their after-tax borrowing cost increased. Thus, for example, if a homebuyer’s mortgage interest rate is 4 percent and her after-tax rate of return on her investment portfolio is 3.5 percent, the loss of the MID would encourage her to pay down her mortgage debt by selling some financial assets.

While we don’t know yet how many homeowners would respond this way, Federal Reserve data give us an idea of how many could take this step if the MID were eliminated or limited. The yellow line in Figure 1 shows that among the homeowners who took out loans on their primary residence in 2016, about 18 percent could have paid down at least some of their mortgage through asset rebalancing. This share generally grows with income: from less than 10 percent among the bottom three quintiles of homeowners to 45 percent for those in the highest income distribution.

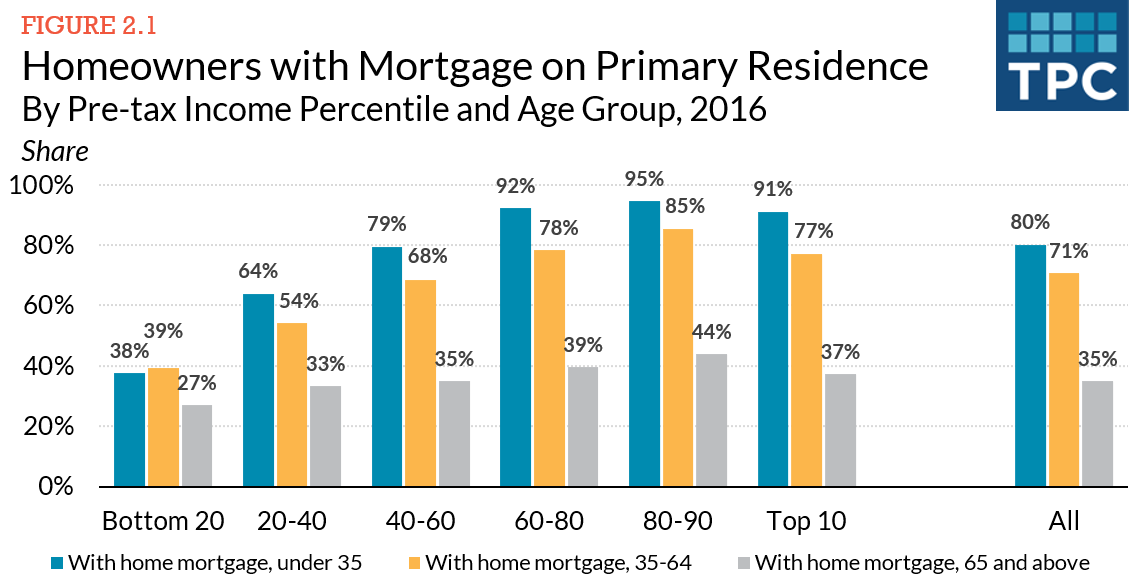

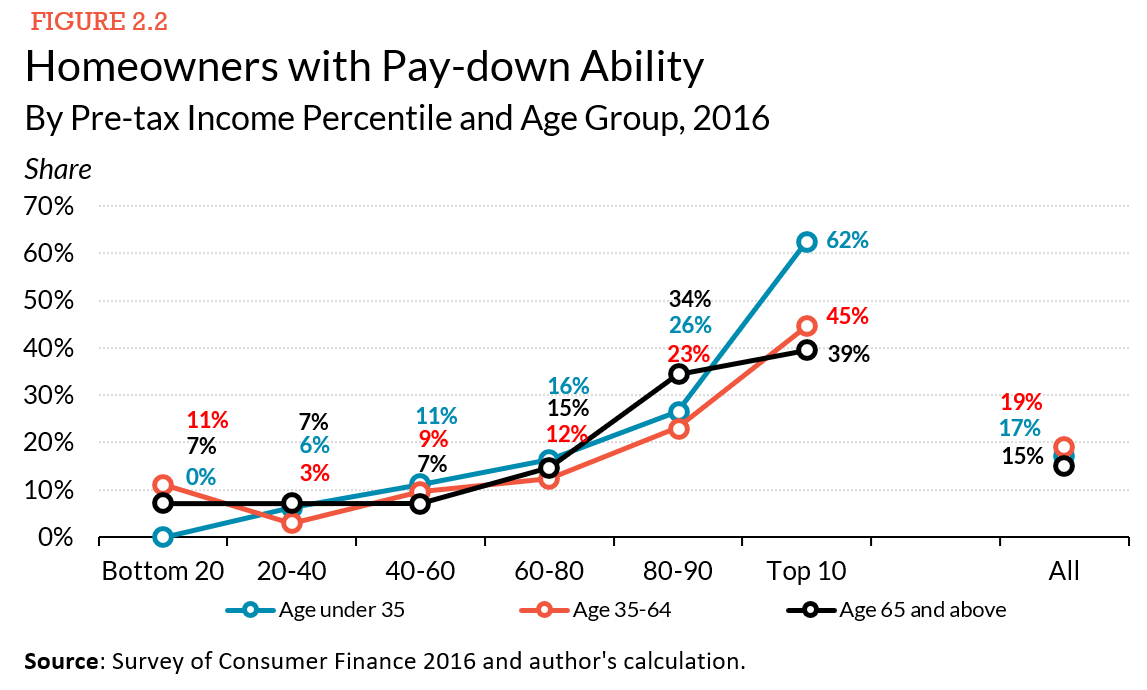

There also is a wide variation by age and income in people’s ability to use assets to pay down mortgage debt. Four-fifths of homeowners under age 35 have outstanding mortgages on their homes, while only slightly more than a third of those 65 and older have mortgage debt (Figure 2.1). Overall the shares of homeowners with mortgages who can pay down mortgage debt are similar among all age groups, and within age groups higher-income homeowners are more likely to be able to pay off their mortgages than lower-income homeowners (Figure 2.2). For example, only about 11 percent of young middle-income homeowners have financial assets available to pay down their mortgage debt, while almost two-thirds of the highest-income young homeowners have those resources. Similarly, fewer than one in ten middle-income seniors could pay down their mortgage debt while about four in ten highest-income seniors could do so.

Higher-income homeowners currently benefit the most from the MID, and they also have the greatest potential to pay down their mortgage debt from existing assets. Since the TCJA preserved the incentive to itemize for most high-income taxpayers, it may not have had a very large impact on the paydown of existing mortgages. However, future limits on the MID could be stronger and have a much bigger impact.