The ongoing COP-27 climate conference will take stock of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and encourage member countries to accelerate their efforts to reach climate goals set in the 2015 Paris Agreement.

Following passage of the Inflation Reduction Act earlier this year, the US is on track to attain a roughly 40 percent reduction from 2005 emissions levels by 2030. However, its Paris goal is to cut GHG emissions at least 50 percent by then. Further policy action will therefore be needed in the near term – but which actions would be most effective?

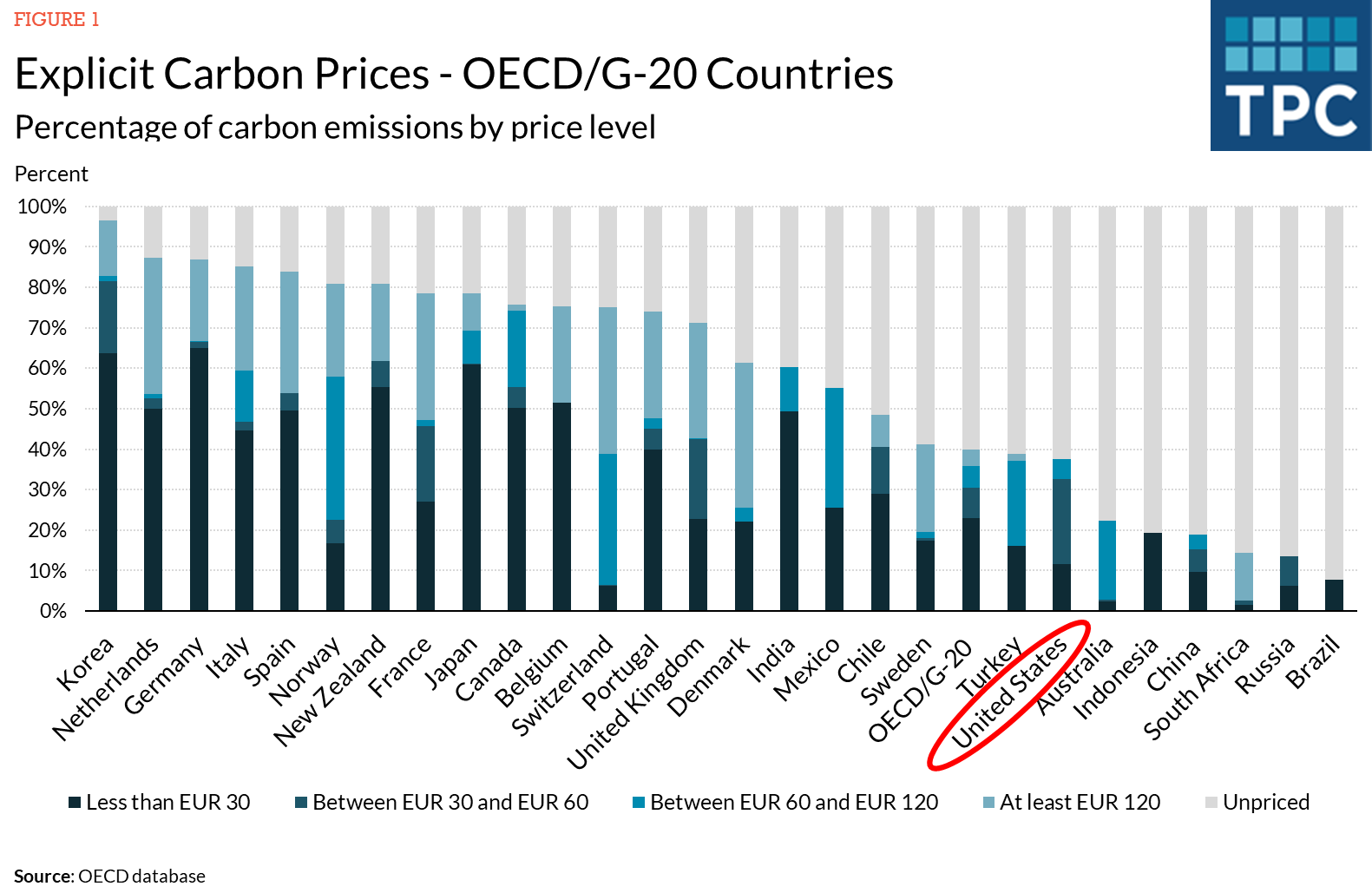

The current US strategy to address climate change relies heavily on “implicit carbon pricing” measures, such as regulation and clean energy tax credits. Most other countries rely heavily on more explicit carbon pricing measures, which include fossil fuel excises, carbon taxes, and cap-and-trade schemes.

The US does use some explicit carbon pricing policies, including state and federal fossil fuel taxes, state-level cap-and-trade schemes, and the new federal methane fee. But these charges are smaller than in most other OECD/G-20 countries.

Explicit carbon pricing tends to be more efficient than implicit pricing. Carbon pricing equalizes marginal emissions reduction costs across sources, ensuring that the lowest-cost methods are used to reduce emissions. Under implicit pricing policies, such as energy efficiency standards and clean energy tax credits, emissions reduction costs are likely to vary across different sources.

Clean energy tax credits and energy efficiency standards also tend to lower energy costs, which stimulates more energy use from all sources. Explicit carbon pricing raises energy costs from fossil fuels, which lowers energy consumption from those sources as well as overall.

And of course, there is a stark fiscal difference between explicit and implicit carbon pricing. Whereas carbon pricing raises revenue, regulations typically do not, and tax credits cost revenue. The IRA clean energy package, which costs about $200 billion over 10 years, will reduce emissions by about as much as a $10/ton carbon tax, which would raise about $400 billion over that period.

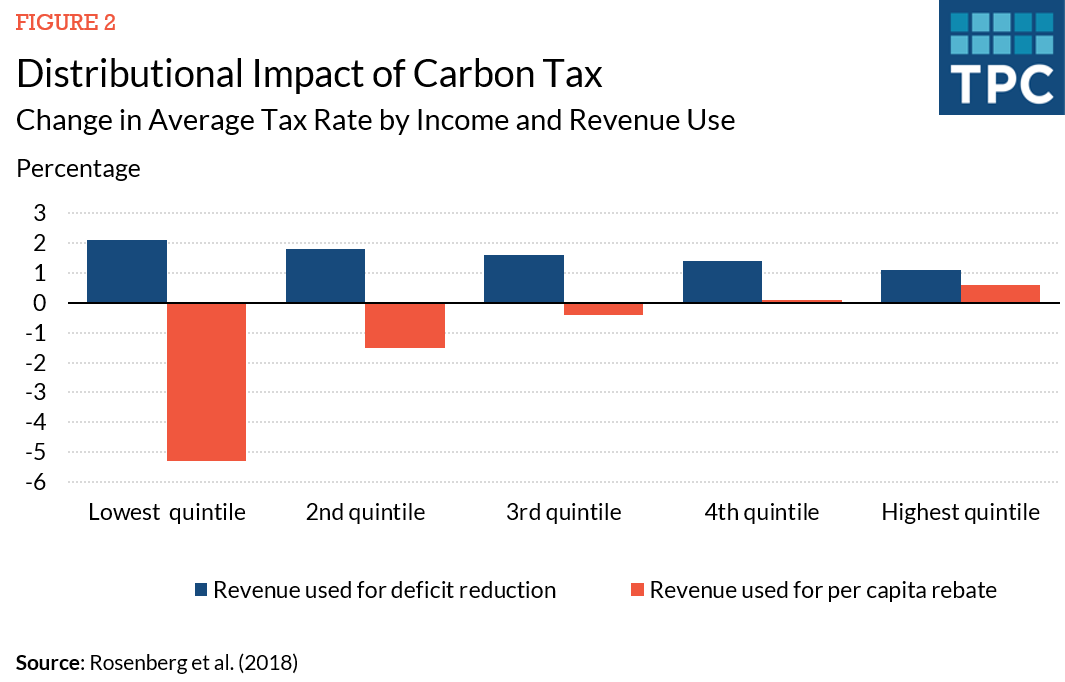

So why doesn’t the federal government rely more on explicit carbon pricing? The main reason seems to be its political unpopularity. Carbon taxes directly raise energy costs, which account for a larger share of low-income households’ income, making carbon taxation regressive. However, the lion’s share of the benefit from not taxing emissions goes to high-income households, which consume far more energy overall.

Keeping fossil fuels cheap is thus an inefficient subsidy to low-income households. A superior approach is to tax fuels according to their true social costs – both carbon emissions and local air pollution—and recycle the revenue back to households. With a rebate or dividend, carbon taxation can be progressive.

While distributional analysis of carbon pricing may show regressivity, that analysis is often unavailable for alternative policies—including doing nothing. As Shuting Pomerleau points out, lack of information about the distributional impact of climate regulation can make it seem preferable to explicit carbon pricing, but its effects may also be regressive. And the environmental justice movement has demonstrated that pollution costs are usually borne disproportionately by lower-income communities.

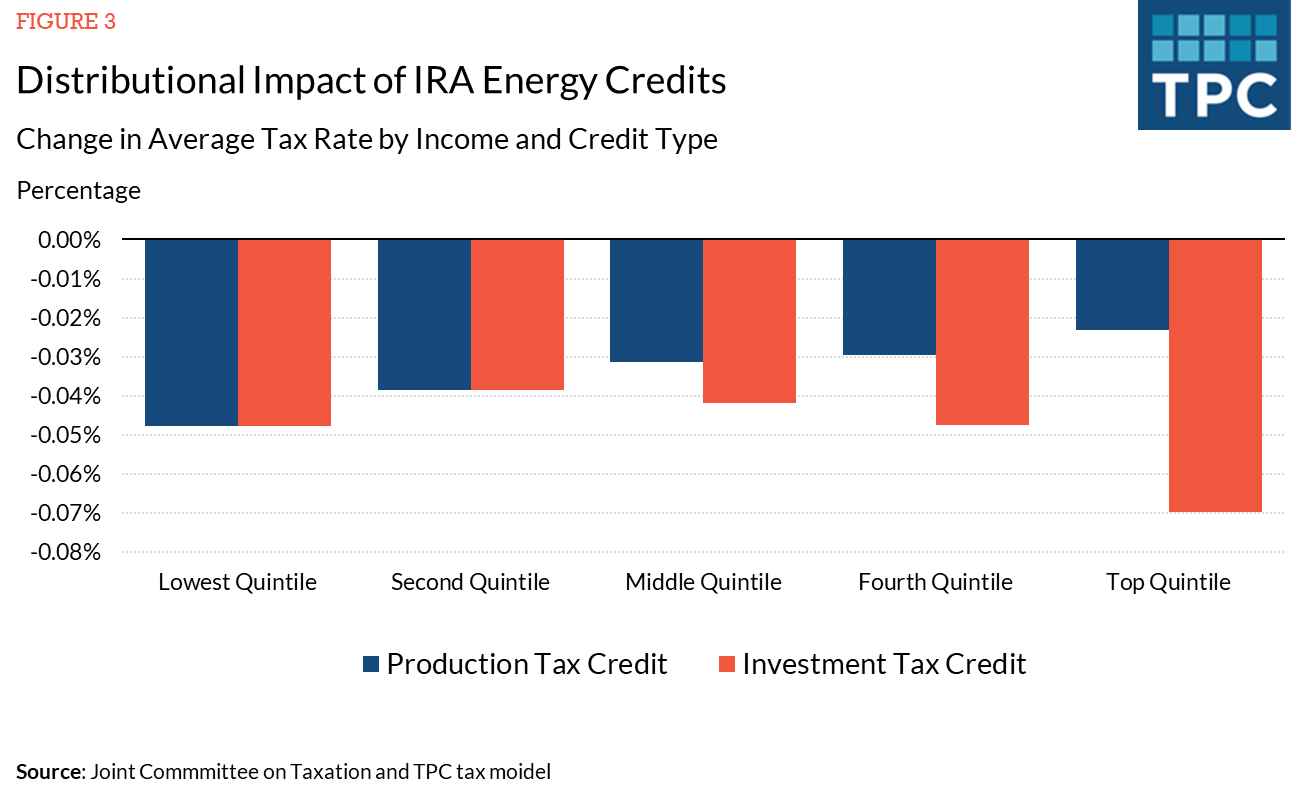

The distributional impact of clean energy tax credits also varies by type. Investment tax credits benefit primarily benefit corporate and pass-through business stakeholders—both labor and capital—while production tax credits primarily benefit energy consumers. Investment tax credits therefore cut taxes more for higher-income households than production credits.

However, this analysis does not account for any reduction in energy prices due to investment tax credits, the benefit of which would be distributed more like the production tax credit.

The best way for the US to close the remaining gap between its current course and its Paris goals would be to introduce a broad-based federal carbon tax with revenue recycling to low-income households. In addition to the advantages cited above, a US carbon tax would super-charge existing clean energy credits by further widening the price gap between clean and dirty energy sources. It would also reduce US trade risks from future EU and Canadian border carbon adjustments (BCAs).