A few years ago, Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote a powerful essay, “The Case for Reparations” for The Atlantic. Reparations, he affirmed, would help close the widening wealth gap between White households and Black households—the result of structural racism rooted in the enslavement of millions of Black people.

How much would it cost to close that gap? As much as $10.7 trillion, according to Duke economist William Darity and his co-author Kirsten Mullen. They suggest that amount could either be paid at once or stretched out over time to the descendants of enslaved people.

Just making good on the cash equivalent of Civil War General William Sherman’s unfulfilled promise of 40 acres and a mule to the families of people freed from bondage would cost up to $3 trillion in current dollars, Darity and Mullen estimate.

And, although numerous options exist to pay for $3 trillion in reparations, those payments would increase the share of total net wealth owned by Black households to just 6.5 percent; by comparison, Black households comprise about 14 percent of all US households.

Who would pay for reparations?

Darity and Mullen’s answer to the financing question: Borrow. After all, policymakers didn’t worry about budget pay-as-you-go (PAYGO) rules when it came to COVID-19 relief totaling over $3 trillion through 2030.

If reparations are about making amends, then individuals and the institutions who benefited from enslaving people should make the payments. That was Sherman’s plan: the 40 acres promised to each family would have come from 400,000 acres confiscated from former enslavers. Today, some supporters, including The Brookings Institution’s Andre Perry, say that a government that once sanctioned treating people as property bears responsibility, not specific individuals.

Of course, taxpayers would ultimately bear that cost.

One possibility: tax the wealthy to pay for reparations. If a goal is to reduce the racial wealth gap, that could be achieved by transferring assets from the very rich to those who face significant barriers to accumulating wealth.

Wealth can be taxed in various ways, including increasing capital gains or estate tax rates, taxing unrealized capital gains, or imposing a wealth tax.

Wealth taxes present many administrative and economic challenges, which would be very difficult to overcome. And another constraint: The Supreme Court might overturn a wealth tax because the Constitution bans direct taxes that aren’t collected evenly across states based on their populations. Ironically, that clause was added to the Constitution in exchange for allowing states to count people held in bondage (but only at three-fifths of a free person) when determining representation in Congress.

But for purposes of this discussion, consider a wealth tax a stand-in for the other ways that assets or capital income could be taxed to pay for reparations.

Taxing wealth to pay for reparations

Reparations weren’t on Senator Bernie Sanders’s campaign agenda, but revenues from his proposed wealth tax would cover most of the costs of fulfilling Sherman’s promise.

Sanders would tax all assets, with rates increasing from 1 percent on net wealth above $32 million to 8 percent above $10 billion (half those wealth thresholds for single taxpayers). The Tax Policy Center estimates his proposal would raise $2.2 trillion over a decade—$3 trillion in wealth taxes that would be partially offset by a reduction in individual income tax collections. (Income tax revenue would fall because some rich taxpayers, hiding assets to avoid the wealth tax, would also underreport capital income.)

Over 97 percent of the wealth tax would be borne by households in the top 0.1 percent of the wealth distribution, or those with at least $36.2 million in net worth in 2021. (Those estimates don’t reflect the pandemic’s impact on the amount and distribution of wealth.)

Reparations could take many forms—including baby bonds, college tuition, and down payments for homes—but some supporters say cash payments must be part of the total package. The $3 trillion of wealth tax receipts would pay for a one-time lump-sum payment of about $66,000 to each Black American alive today, including people who identify both as Black and another race. Payments per recipient would be larger if they were limited only to the descendants of enslaved people, as Darity and Mullen propose. And, as compensation for past injustices, the payments would not be means-tested.

Recipients wouldn’t pay taxes on reparations, though they would be taxed on any income they earn from investing the payments. Just as reparations would not be means tested, recipients could be exempted from the wealth tax. But without rigorous enforcement, rich taxpayers may fake claims of enslaved ancestors to avoid sizable tax hits.

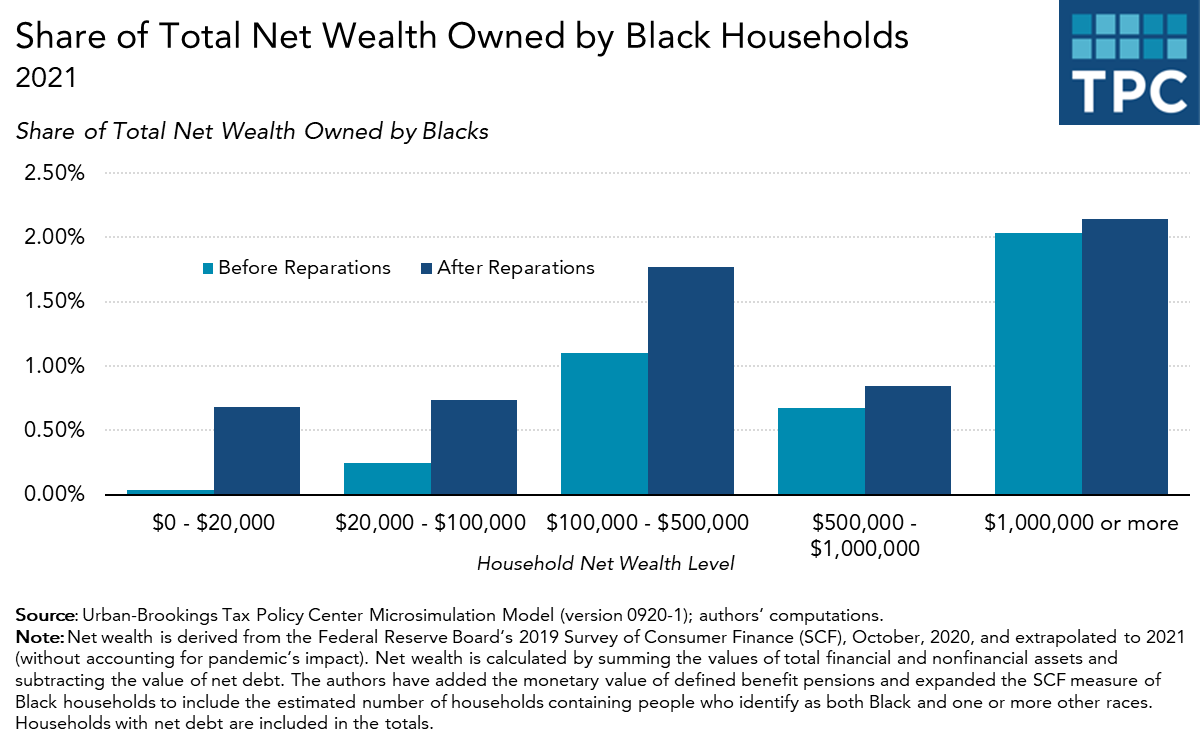

Overall, a $66,000 one-time reparations payment would increase the net wealth of Black Americans by 160 percent. The share of total net wealth held by Black households would rise from 4 percent to 6.5 percent in 2021. The share would increase the most among Black households with less than $20,000 in assets before reparations, although they’d still hold less than 1 percent of all total net assets owned by US households.

Could reparations happen?

Reparations remain a political long shot. Still a few cities, such as Evanston, Illinois, Asheville, North Carolina, and St. Paul, Minnesota, are pursuing the idea. And during the campaign, President Biden said he could support reparations if studies found direct payments to the descendants of enslaved people to be viable.

Identifying who would pay for reparations should be considered at the same time.