By roughly doubling the standard deduction and limiting the deduction from federal taxable income of state and local taxes (SALT), the Tax Cut and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) significantly reduced the tax benefits of homeownership, especially for middle-income households. Not only does it cap the deductibility of state and local taxes, including local property taxes, it also substantially reduces the number of taxpayers who will itemize deductions at all, including those who pay mortgage interest.

As a result, it raises important questions about the future viability of tax subsidies that primarily benefit higher-income taxpayers who own expensive, highly-leveraged homes. These changes made homeownership tax subsidies even more upside-down than pre-TCJA tax law and provide a tax incentive to further concentrate the distribution of private wealth.

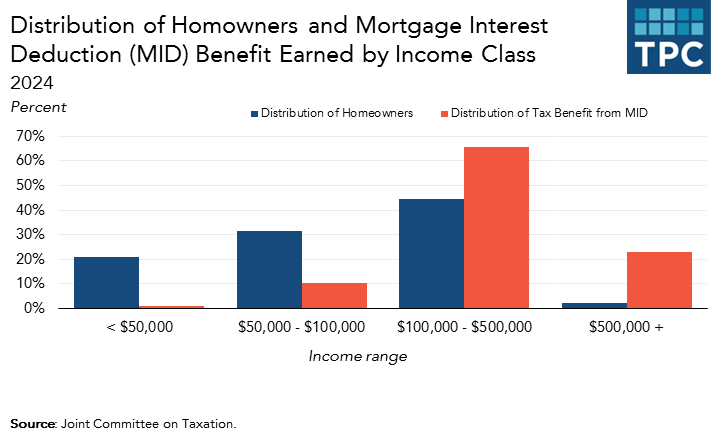

The Congressional Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) recently released projections on the future distribution of some of the tax benefits of homeownership. Out of 77 million projected homeowners in 2024, only about one-fifth will make $50,000 or less. Yet, they’ll comprise about half of all households, homeowners and nonhomeowners alike. These taxpayers with annual incomes under $50,000 will get only about 1 percent (or less than $400 million out of $40 billion) of the overall tax subsidy for home mortgage interest deductions. Meanwhile, households with more than $100,000 of income will garner almost 90 percent of the subsidy.

These estimates for the mortgage interest deductions understate the total value of tax benefits from homeownership. Property tax deductions are also skewed to the rich and the upper-middle class. At the same time, it is more beneficial to build up home equity largely tax-free than to pay income tax on the returns from money kept in a savings account. This additional incentive also benefits the haves more than the have-nots because it is proportional to the amount of equity a homeowner possesses. So those with a large amount of home equity are far better off than new, usually younger, homeowners who rely heavily on borrowing to purchase a home.

There is something of a paradox to the new tax law, however. The increase in the standard deduction, and the caps on deductions for home mortgage interest and state and local tax payments are all steps that make the overall tax system more progressive. And the reduction in tax incentives probably put a small break on inflation in the value of housing, making it a bit more affordable for both renters and homeowners.

Still, as a matter of homeownership policy, the result is that only a little over one tenth of taxpayers—those who will still itemize after the TCJA—will have the opportunity to benefit from most tax subsidies for homeownership. And that will require advocates for extending ownership incentives to more low- and middle-income groups to make the case not simply for better distributing existing tax subsidies but for maintaining any at all. As the increase in the standard deduction shows, there are a lot of ways of promoting progressivity that do not entail subsidizing homeownership.

The case for homeownership subsidies in the tax code and elsewhere rests mainly on the following two grounds: (1) homeownership is a way of promoting better citizenship and more stable communities; and (2) homeownership helps improve wealth accumulation by nudging many who might not otherwise save to do so by paying off mortgages and making capital improvements on their houses.

The saving argument is one that does apply mainly to low- and moderate income households. Homeownership is the primary source of saving for these households, even more important than private retirement saving. If one cares about the uneven distribution of wealth, and related issues of financing retirement for moderate-income households, then encouraging wealth accumulation through housing may be an appealing strategy.

The bottom line: When it comes to homeownership, the TCJA has left the nation with an upside-down tax incentive that applies to only about one-tenth of all households—nearly all of them with high incomes.

Such a design doesn’t pass the laugh test for political sustainability. The new tax law’s crazy remnant of a homeownership tax subsidy should encourage policymakers to rethink housing policy, including tax benefits and direct spending programs for both renters and owners. Given the structure of the TCJA’s tax subsidies, the bar is relatively low for policymakers to find an improvement.