The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) cut federal tax revenues by nearly $2 trillion over its first decade, with almost all the benefit going to higher-income households and corporations. But, that’s not surprising. The bill passed without a single Democratic vote, and in the current environment inequality is perceived as a partisan issue. But that is a misperception. The political viability of pro-growth policies depends on sharing economic gains broadly—something that does not happen automatically.

A tax system designed to share the gains from economic growth could enable other pro-growth reforms. By contrast, a system that allows middle-class people to fall further behind will fuel populist anti-growth policies that could leave all income groups worse off.

A far better approach would be a tax reform that makes it possible for people who work hard to fully share in the gains from an expanding economy. One way to do it: a universal earned income tax credit (UEITC)—a one-for-one match on the first $10,000 of earnings delivered through a refundable tax credit. It’s like the existing earned income tax credit, but is bigger, doesn’t phase out, and is available to every worker regardless of family composition or household income. It would also be designed to grow with the economy.

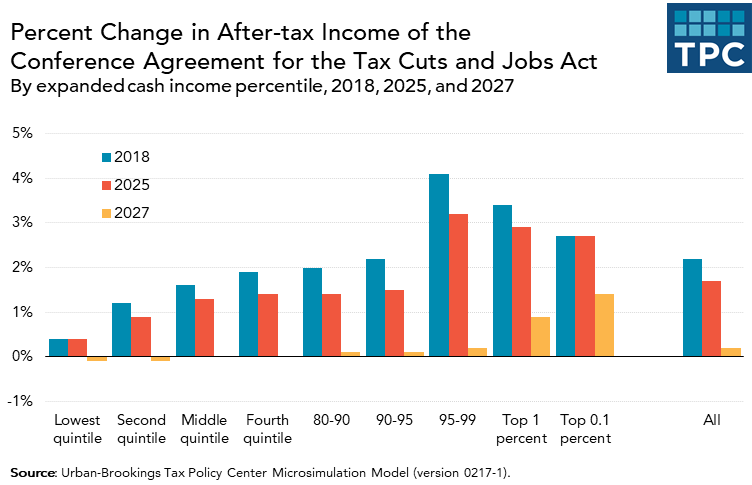

The TCJA didn’t do much for low-income households. It raised the standard deduction and cut marginal tax rates, but that was worth little or nothing to people who do not owe much income tax. The TCJA doubled the child tax credit from $1,000 to $2,000, but only $400 of that increase was made refundable (available to filers who do not owe income tax). In 2018, the lowest income-households received an income boost from the TCJA of less than 1 percent, while those with the highest incomes saw their after-tax incomes rise by 3 percent or more. (See figure 1.) After 2025, almost all the individual income tax provisions expire, but less generous indexing of the tax code for inflation is permanently built into the system. Year-after-year, this slower indexing will raise income taxes for all taxpayers, but especially for those with lower incomes.

The Tax Reform Act of 1986 (TRA86) took a very different approach. It was designed to be distributionally and revenue neutral. President Reagan touted its benefits for low-income families when he signed it, calling it “…the best anti-poverty bill, the best pro-family measure, and the best job-creation program ever to come out of the Congress of the United States.”

Politics may be more partisan now, but a quick review of American election politics suggests that even pro-growth policies may not be self-sustaining if many voters feel they are losers.

President Trump’s 2016 promises of trade barriers and immigration restrictions were aimed at easing middle- and-working-class anxiety. Many Democratic primary candidates this year are proposing more regulation of businesses and explicitly punitive taxes on wealthy individuals. Some modern day luddites are even proposing robot taxes, designed to suppress the advance of labor-saving technology. These policies might reduce overall inequality, but they also could entail large economic costs.

The right policy response depends on a correct diagnosis of the problem. 2020 Democratic candidate Andrew Yang proposes a $1,000 per month universal basic income (UBI) financed by a value-added tax (VAT) as a cure for inequality. If the problem is that middle-class people don’t have sufficient income to pay for health care, education, and other costs of living directly raising their incomes is more efficient than a menu of government-provided goods and services. However, if the main problem is that the market does not adequately reward work, a better approach may be to subsidize wages so people who work hard can get ahead.

That’s why I proposed the UEITC. Workers could have the credit added to their paychecks or collect it as a lump sum when they file their tax returns. Like other earnings, the UEITC would be subject to income tax. I’d also increase the child tax credit from $2,000 to $2,500 and make it fully refundable. The UEITC would be funded by a broad-based 11 percent VAT.

Importantly, the maximum UEITC would be indexed to changes in GDP. If the economy grows by 5 percent, the maximum credit would increase by 5 percent to $10,500. For the first time since the 1970s, working families would fully share in the gains from economic growth. This could bolster support for pro-growth economic policies like freer trade and more open immigration.

People who care about our economic future need to think harder about how to distribute the gains from growth more equitably. Otherwise, they will be ceding the policy agenda to those who are indifferent or even hostile to the benefits of growth.

When most TCJA individual income tax provisions expire after 2025, Congress will have a chance to rethink tax policy. Tax reform 2.0 could both boost the economy and help middle-income working people share in the newly created wealth.

A version of this post was published in the AEI blog series, “Trump’s tax reform happened, now what?”