Ballooning oil company profits have produced a volley of “windfall profit tax” proposals. How well would their different provisions meet the near-term US policy goals of increasing tax revenue from oil profits without deterring domestic production or raising consumer prices?

The US currently taxes petroleum production in two main ways: the income tax and an ad valorem royalty of 18.5 percent for oil pumped on federal lands. Effective income tax rates for both corporate and pass-through oil producers are lower than for most other industries due to sector-specific tax breaks.

Tax revenues from domestic oil production profits are lower in the US than in most other major oil producing countries. Moreover, that share falls when oil prices rise due to the US’s heavy reliance on royalties, since oil companies’ gross receipts rise much less than profits as prices rise.

The US could address this by increasing profit taxation relative to royalties. An obvious first step would be to repeal existing profit tax breaks for the oil and gas industry, which would raise about $3.5 billion annually. The second step would be either to increase existing profit tax rates on petroleum or to impose an additional profit tax.

To avoid reducing domestic production, the petroleum profit tax base should be limited to excess returns, or “rents.” Unlike an income tax, a rent tax does not burden marginal investments—those that just break even after taxes. The main differences between a rent tax and an income tax are that rent taxes allow full expensing of investment and exclude financial flows like interest expense.

Ideally, a petroleum rent tax should only apply to “upstream” extraction activities, not “downstream” refining or distribution. Natural resource rents arise from exploitation of a fixed natural resource, while downstream profits rely on fungible capital and labor inputs. Limiting the petroleum profit tax base to rents thus requires separate tax accounting for upstream activity, or “ring-fencing.”

There are many ways to tax oil rents. The simplest way for the US would be to increase income tax rates on petroleum extraction. Because 100 percent “bonus depreciation” allows most equipment to be expensed, the US income tax now simulates a rent tax, although it also includes financial flows.

Returning the corporate tax rate on petroleum extraction to 35 percent would restore tax symmetry for any undepreciated investment made before 2018. Since many US oil companies are organized as pass-throughs, an equivalent surtax would need to be imposed on their profits.

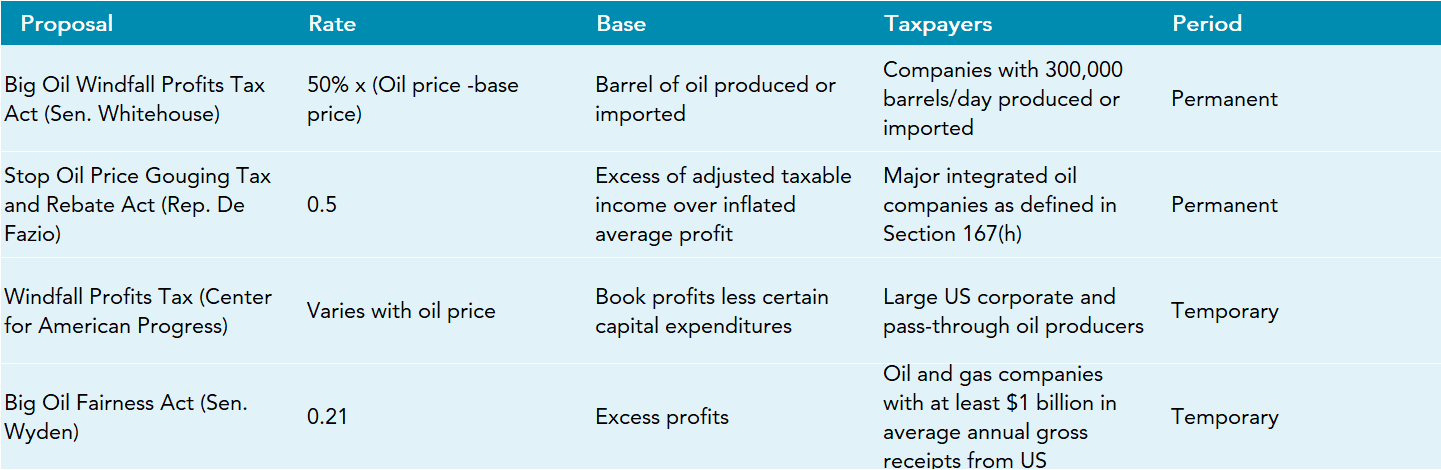

Proposals by Representative Pete DeFazio (D-OR), the Center for American Progress, and (reportedly) Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR) would impose an additional tax on petroleum profits. These proposals would all increase the government share of oil profits but less efficiently than a permanent rent tax.

The Center for American Progress (CAP) proposal to tax book income, which deducts capital expense in line with economic depreciation, would likely tax normal returns. By contrast, the DeFazio and Wyden proposals would begin from taxable income, which currently permits full expensing.

The DeFazio proposal would adjust taxable income for financial flows, while the Wyden proposal would reportedly provide an added deduction for current-year investment. These features move the income tax base in the direction of a rent tax.

The CAP and Wyden proposals call for temporary windfall profit taxes. Temporary tax increases, particularly for industries with long-lived investments like the oil industry, distort the life-cycle tax burden and increase investor risk.

An excise tax on domestic production, as proposed by Senator Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI), is effectively a royalty. Royalties burden the normal return to investment heavily because they don’t allow deduction of production costs.

The Whitehouse proposal eases this effect by tying the tax to price increases above a benchmark and limiting it only to major oil companies. Progressive royalties raise more revenue as oil prices rise than flat-rate royalties, though not as effectively as a rent tax. Imposing the excise only on Big Oil, whose US production is concentrated in lower-cost conventional wells, focuses taxation on excess returns.

All four windfall profit tax proposals would target only larger oil companies for both economic and political reasons. Exempting smaller producers, which tend to engage in higher-cost drilling that is more sensitive to changes in price, could avoid depressing domestic supply. And, politically, lawmakers may prefer to focus attention on rising profits of big, publicly owned oil corporations.

However, raising tax rates on a subset of companies within an industry distorts investment incentives and reduces production efficiency. Since a properly designed rent tax would only burden producers with sufficiently high profits, there should be no need to exempt marginal producers.

The US can tax a larger share of petroleum profits without discouraging production by increasing taxes on petroleum rents. And the way to do that is by eliminating existing tax breaks and imposing a permanent petroleum rent tax.