Reforming the mortgage interest deduction (MID) could raise federal tax revenue and make the tax system more progressive. But some taxpayers, especially those with high incomes, are likely to mitigate any tax increase associated with the reform by selling some financial assets and paying down their mortgage debt. This practice would reduce federal revenues associated with the reform and also could make reforming the MID somewhat less progressive than it would be otherwise.

Thanks to a grant from the Peter G. Peterson Foundation, the Tax Policy Center (TPC) can simulate proposals to reform the MID, and include the effects of taxpayers responding to the changes by paying down mortgage debt with their financial assets. We provide some examples in a chartbook, which shows the revenue and distributional implications of mortgage paydown.

Reforming the MID has long been a topic of tax policy discussion because it is a poor incentive for moderate income households, who rarely claim itemized deductions, to purchase a home. At the same time, the deduction encourages high-income households to take out loans to buy more expensive and larger houses rather than investing in other assets. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act almost doubled the standard deduction and capped the deduction for state and local taxes at $10,000 for tax years 2018 through 2025. As a result, the number of taxpayers itemizing deductions and claiming the MID was reduced substantially, and the benefits of the MID were more concentrated at the upper end of the income distribution.

If the MID is repealed, higher-income taxpayers would have the greatest ability to mitigate the impact of the potential tax increase. A previous blog explored the potential of mortgage paydown following repeal of the MID. Higher-income homeowners would be more responsive than less well-off homeowners because they have more financial assets available to pay down mortgage debt.

Revenue Effect

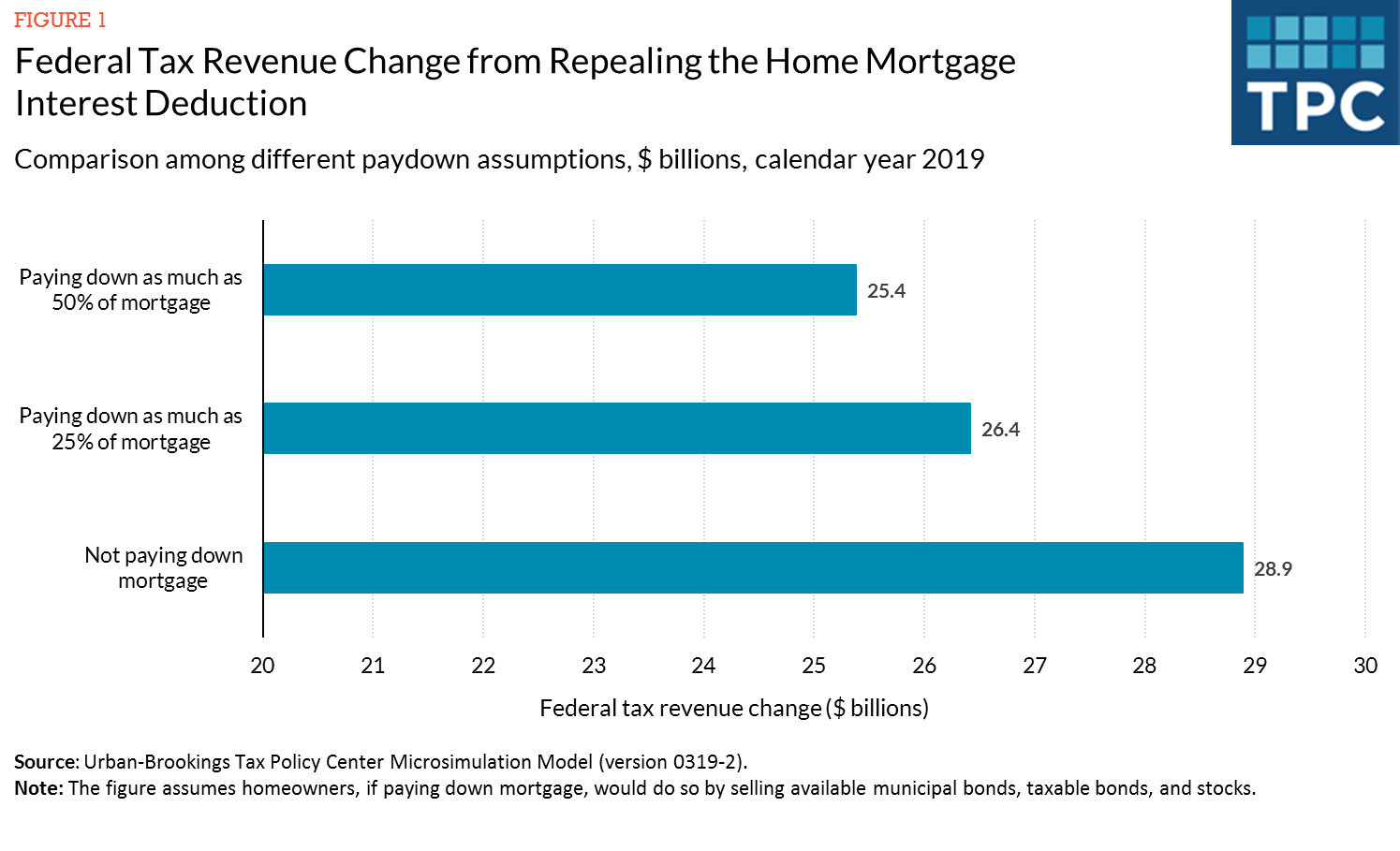

The overall revenue effect of incorporating mortgage paydown behavior is notable but modest. Figure 1 compares the revenue effects of repealing the MID under three different assumptions: (1) taxpayers don’t pay down a mortgage at all; (2) taxpayers pay down as much as 25 percent of their mortgage; and (3) taxpayers pay down as much as 50 percent of their mortgage. More options are shown in the chartbook.

If taxpayers respond to repealing the MID by paying down some of their mortgage debt, they would reduce the tax revenue gain from this proposal. For example, if taxpayers aim to pay down up to 25 percent of their debt, the revenue gain in 2019 from repealing the MID repeal would be about $26.4 billion, or 9 percent lower than if they did not respond by paying down any mortgage debt. (TPC used 2019 for this analysis to avoid complications associated with trying to model the 2020 economy).

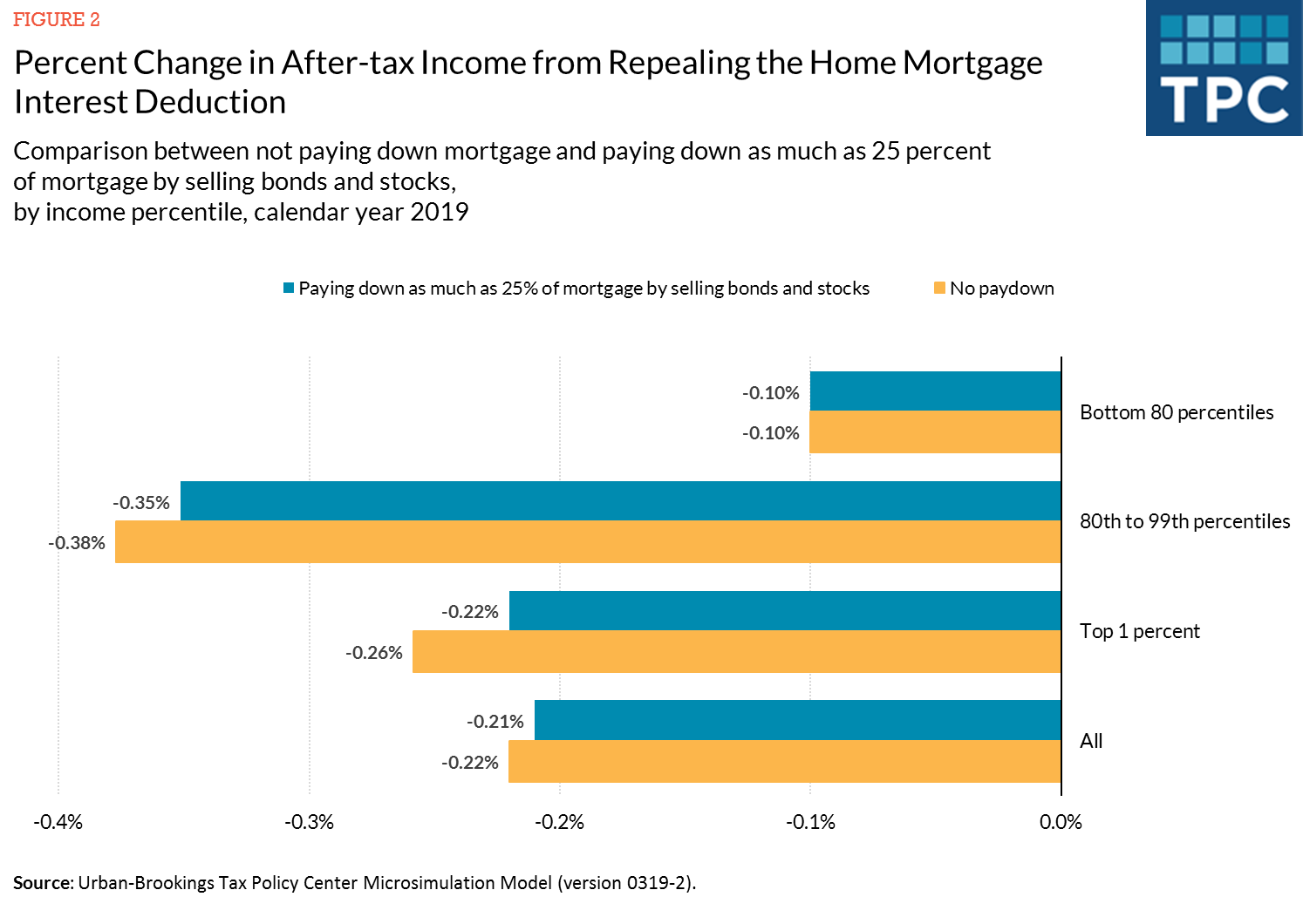

Repealing the MID would make the federal tax system more progressive by raising taxes on higher income households. But the effects would be smaller if homeowners respond by paying down a portion of their mortgages. Figure 2 shows how the distribution of after-tax income would change under the assumption of no mortgage paydown and under the assumption of home-owners subject to the repeal paying down up to 25 percent of their mortgage debt in response to losing the deduction.

Repealing the MID would reduce after-tax income for households in the 80-99th percentiles of the income distribution by the largest percentage amount. If these households do pay down up to 25 percent of their mortgage, this group would pay about 0.35 percent of their after-tax incomes in additional tax, compared to 0.38 percent if they do not reduce their mortgage loan balances. Paydown behavior reduces the estimated tax increase the most for households in the top 1 percent (from 0.26 to 0.22 percent of after-tax income). Because taxpayers in the bottom 80 percent of the income distribution have limited financial assets to pay down mortgage debt, they would be unable to save much in taxes through this paydown practice.

Overall, if Congress reforms the MID, some high-income taxpayers are likely to respond by paying down a portion of their mortgages. If taxpayers respond this way, the Treasury will collect somewhat less revenue than if no paydowns occur. The work outlined in this blog points to the benefits of incorporating potential paydown behavior into tax models.