House Budget Committee Republicans have identified eliminating the federal tax exclusion for interest earned on municipal bonds, or “Muni” bonds, as a large potential revenue raiser as Congress considers whether to extend expiring provisions of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA). By one estimate, this could raise $250 billion over ten years.

State and local governments rely on Muni bonds to finance long-term capital investments such as transportation infrastructure and public buildings. The municipal bond market is huge: By the end of 2024, its total valuation was estimated at $4.2 trillion, with new issuances of over $500 billion that year.

What might be the consequences of ending tax exemption for Muni bonds for state and local governments and their residents?

How might the Muni bond market change?

Muni bonds yields vary depending on duration and estimated risk. As of early 2025, 30-year Muni bonds with a rating between AAA and A had yields ranging from 3.9 to 4.5 percent, while 30-year Treasury bonds yielded around 4.8 percent. Repealing the exemption would raise borrowing costs for state and localities, as taxable investors would require higher yields.

While the yield gap between taxable and tax-exempt bonds is smaller than expected from the tax advantage, likely due to a mix of liquidity concerns and default risk, removing the exemption would likely trigger a sell-off as investors seek higher yielding alternatives. That would push yields and borrowing costs higher, potentially negatively impact state and local government finances.

Which states and cities would be most affected?

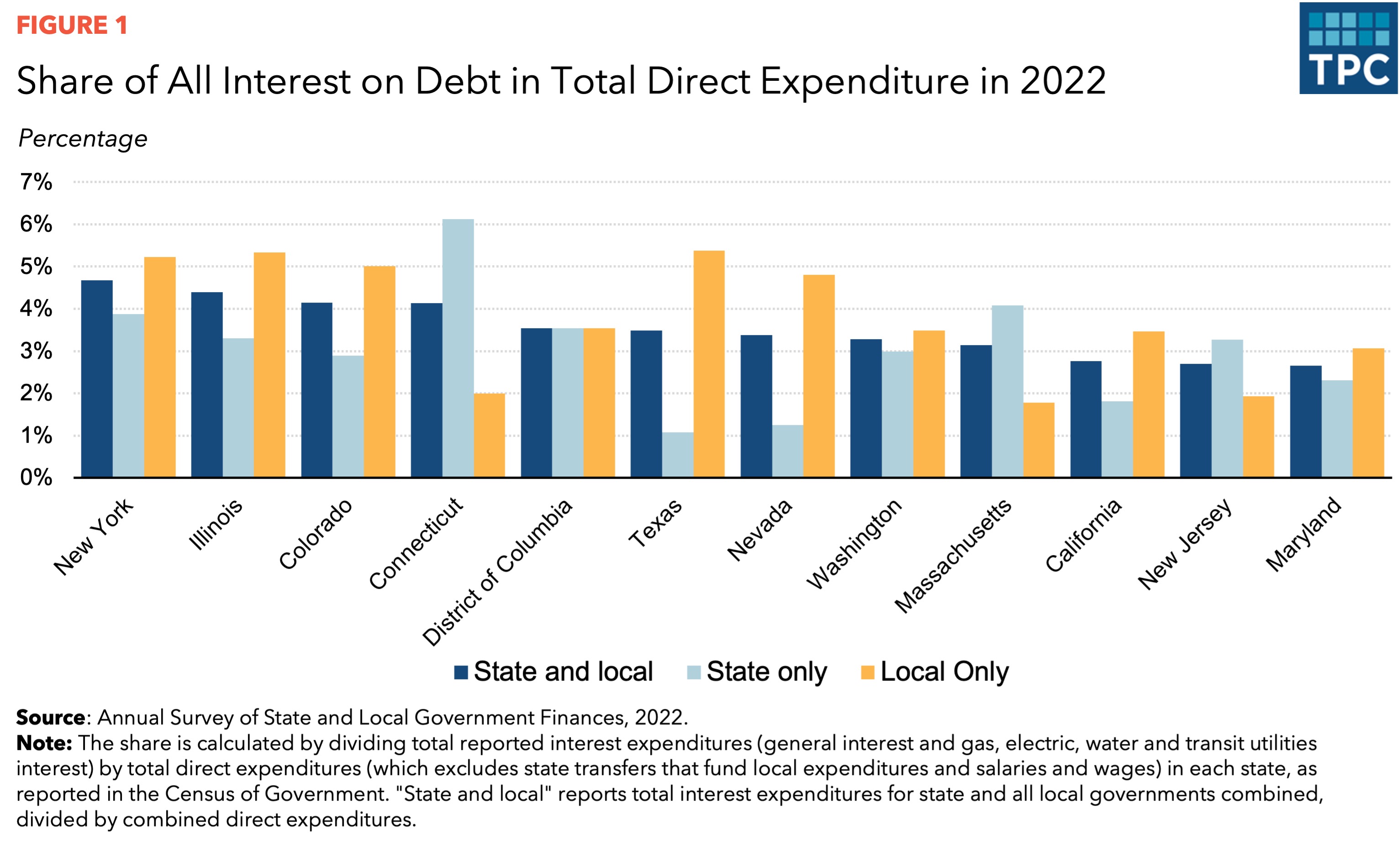

In 2022, the latest year for which comprehensive data are available from the US Census Bureau, total interest on debt for state and local governments was $120 billion. Total interest expenditures were between 0.5 percent and 4.7 percent of total direct expenditures for state and local governments combined, with an average of about 2.8 percent in the US. New York, Illinois, Colorado, and Connecticut had the largest combined share (Figure 1).

In Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New Jersey the state share of interest was larger than the local share. In Illinois, Colorado, Texas, Nevada, and California it was the opposite.

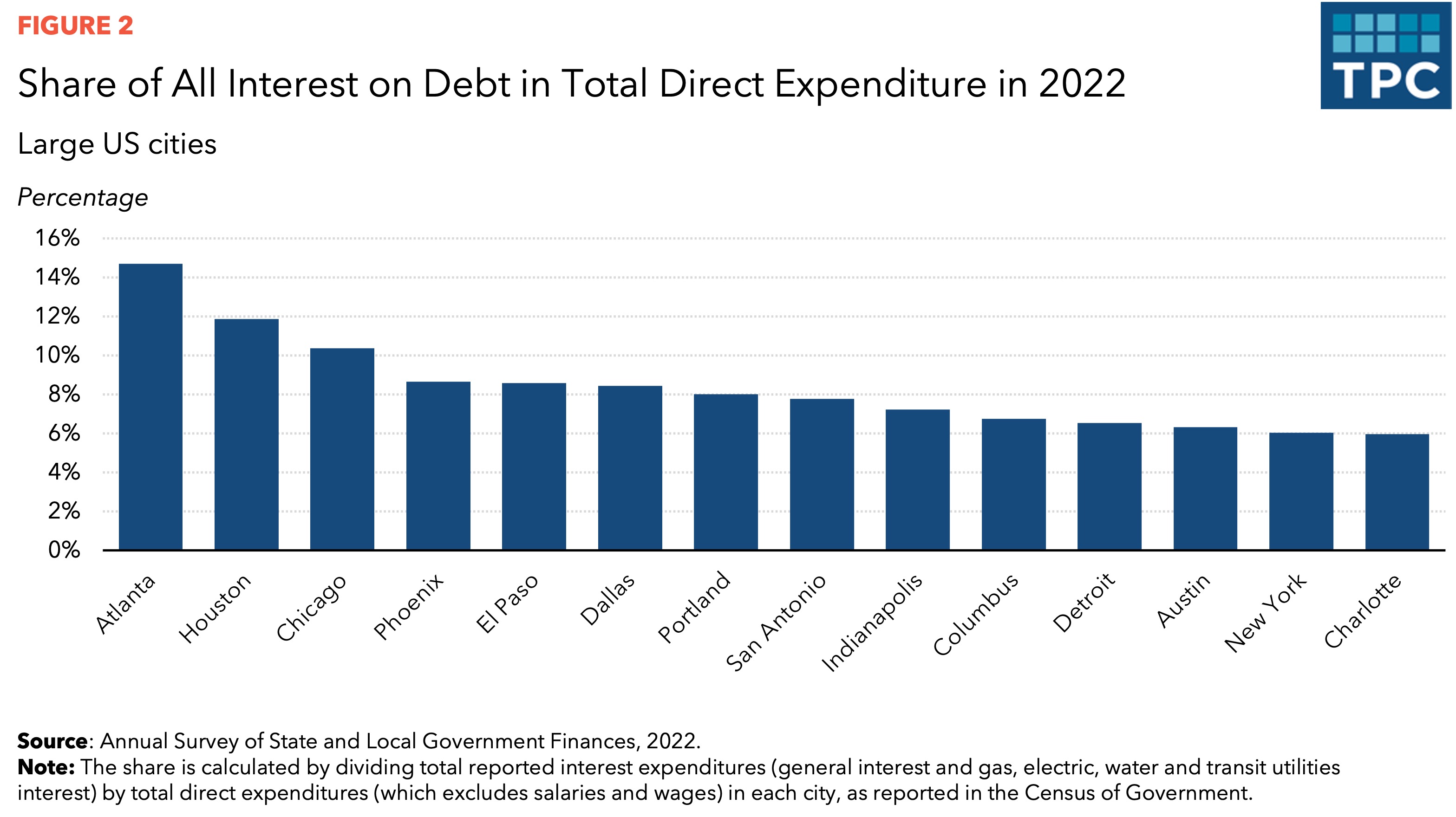

For many large cities and their governments, higher borrowing costs could become a significant chunk of their budgets. Figure 2 illustrates this for cities with populations over 500,000. In 2022, they had an average share of interest expenditures of about 5.6 percent, but with significant variation. Atlanta, Houston, and Chicago had shares over 10 percent, while New York had a 6 percent share.

Policymakers should consider the tradeoffs of taxable Muni bonds

Section 103 of the federal tax code has excluded income earned on state and local bonds since its inception in 1913. Congress originally excluded income from local bonds due to concerns about the constitutionality of its taxation. The exclusion has remained a feature of the federal tax code despite that concern being now obsolete, as Supreme Court decisions chipped away at intergovernmental tax immunity.

There are some economic arguments against the exemption. It can be an inefficient subsidy, because the cost to the federal government is larger than the benefits received by state and localities. And the wealthiest investors enjoy a disproportionate amount of the benefits of the exemption—the wealthiest 0.5 percent had a 42 percent holding share in 2013. Lowering borrowing cost can also lead to a bias toward debt financing and overinvestment in some projects.

However, a repeal may lead to less investment in state and local infrastructure without another form of subsidy or transitional measures by the federal government. (State and local governments are responsible for about 80 percent of total spending on roads, bridges, water utilities, and other infrastructure, not including their spending from federal funds.) Alternatively, state and local governments would need to increase local taxes or cut spending to maintain infrastructure spending.

Before repealing Muni bond tax exemption, Congress should carefully consider potential short and long-term impacts on state and local governments and their taxpayers.