As the lame duck Congress considers further stimulus for an economy that is rebounding but still deeply troubled, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) and others have insisted on a “skinny bill” that would focus on a handful of measures they deem most essential.

State and local government assistance has not been on their “essential” list.

While the elements of a smaller relief package this year remain a matter of debate, higher-than-expected state tax collections do not obviate the need for additional state and local fiscal relief. Indeed, a close look at the effects of prior federal aid supports the argument for more assistance to these governments.

Congressional Aid Worked

It’s true that states like California, Colorado, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Virginia are seeing higher tax collections than forecasters expected when the economy was falling off a cliff last spring. And in some states, March through September revenues even exceeded the comparable period in 2019.

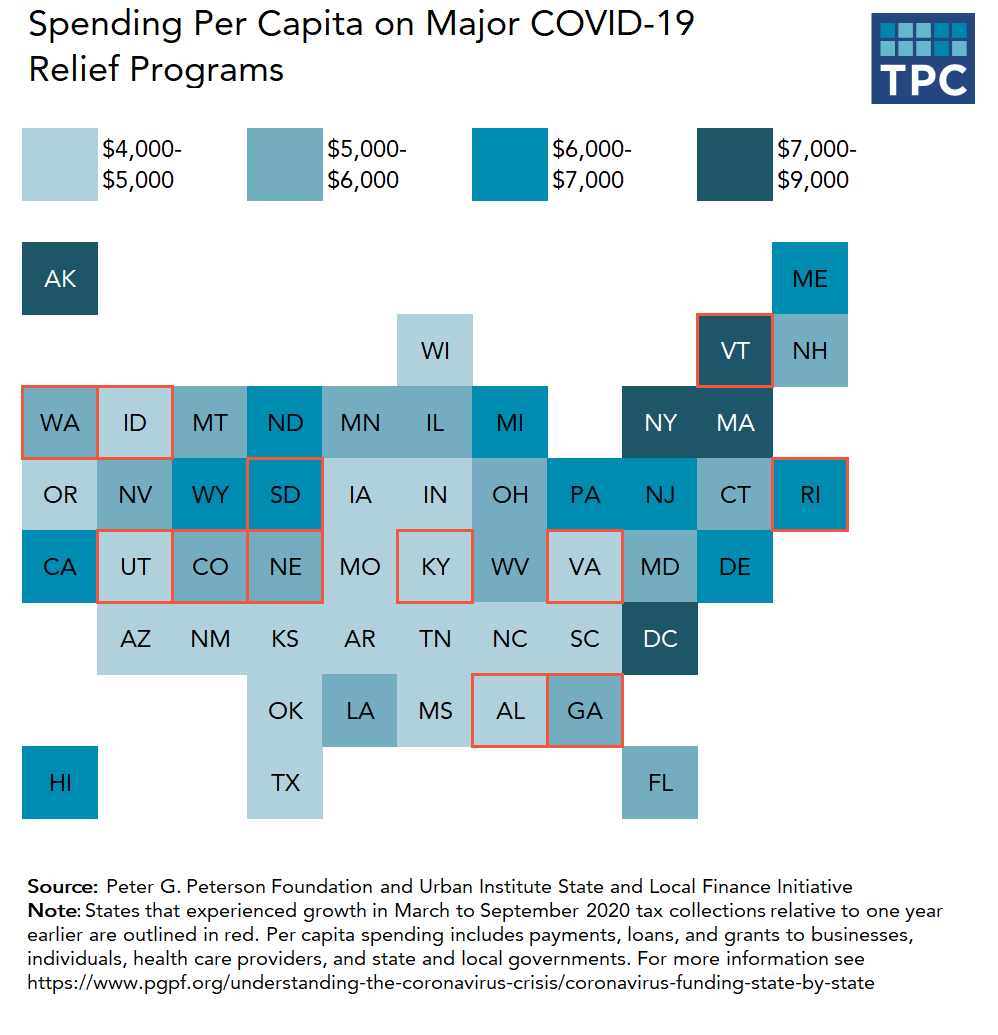

But not all states enjoyed such a positive revenue surprise. And where they did, those revenue improvements resulted in part from the relief measures Congress enacted in the Spring.

In March, Congress approved direct fiscal relief that states and localities have now spent. Though I and others criticized these payments as inadequate, they still helped.

But, relief bills enacted in March and April also included significant financial assistance to individuals and businesses affected by the downturn—money that has been critical to supporting state and local economies and revenues. That federal aid kept personal incomes and consumption (especially of goods) afloat and prevented some of the worst feared budget losses.

Back in July, the Texas Comptroller attributed an unexpected surge in sales tax revenues to enhanced federal unemployment benefits. He also worried about what would happen to sales taxes should those benefits expire on schedule.

And that is now the problem. These programs have all run out of money or will expire at the end of the calendar year—just when a severe new wave of the pandemic is again slowing commerce across the country.

This is a big problem

Meanwhile, states and local governments must balance their budgets even as they still face plummeting tax revenues and rising costs for programs like Medicaid.

Balanced budget rules together with abrupt revenue losses in April and May caused states and localities to shed jobs (1.3 million since February) and cut services, causing hardship for residents and putting the national economic recovery at risk.

And the problem is expected to get worse because state tax collections lag economic activity and due to rising costs of the “third wave” in COVID cases and hospitalizations.

This Downturn is Different

It cannot be overstated how much the COVID-19 economic slowdown is not like past recessions.

While all recessions are worse for people with low versus high incomes, the current economic slump has been especially destructive for low-income workers because it predominantly affects restaurants and other businesses in the service sector.

That’s especially bad for states that rely on the leisure and hospitality industry. But it hurts all states and localities because, in addition to providing basic services, these governments maintain the country’s social safety net.

There are also important differences between states and many cities. Because high-income workers have been less likely to lose their jobs or have hours cut and the stock market remains strong, states such as California and New York have not seen the income volatility that can send their revenues into a tail spin.

It is a different story for cities, which tend to rely on location-specific taxes, fees, and charges. If COVID-19 is indeed a reallocation shock and former restaurant workers will (eventually) get hired at places like Home Depot, that may be great for those workers and state revenues. But cities still will miss out on economic activity that used to happen within their borders (and be subject to taxes there) and now has moved elsewhere.

Some improvement in state and local revenues is no excuse for Congress to ignore those governments in the next relief bill. Since the election, many commentators have extolled the virtues of divided government. But helping states and localities in the fiscal equivalent of a 100-year flood should not be partisan issue. It’s time for Congress to get to work.