On September 30, President Trump held a fundraiser in St. Paul MN, an event that received a lot of attention because he participated even after a top aide tested positive for the coronavirus. Early the next morning, hours after the fiscal year ended, Trump signed a continuing resolution (CR), a stopgap spending bill to keep the government operating until December. It got almost no attention.

It was barely news that the President’s signature avoided a costly government shutdown or that the Senate had never even considered any of the 12 annual appropriations bills that are supposed to fund the government.

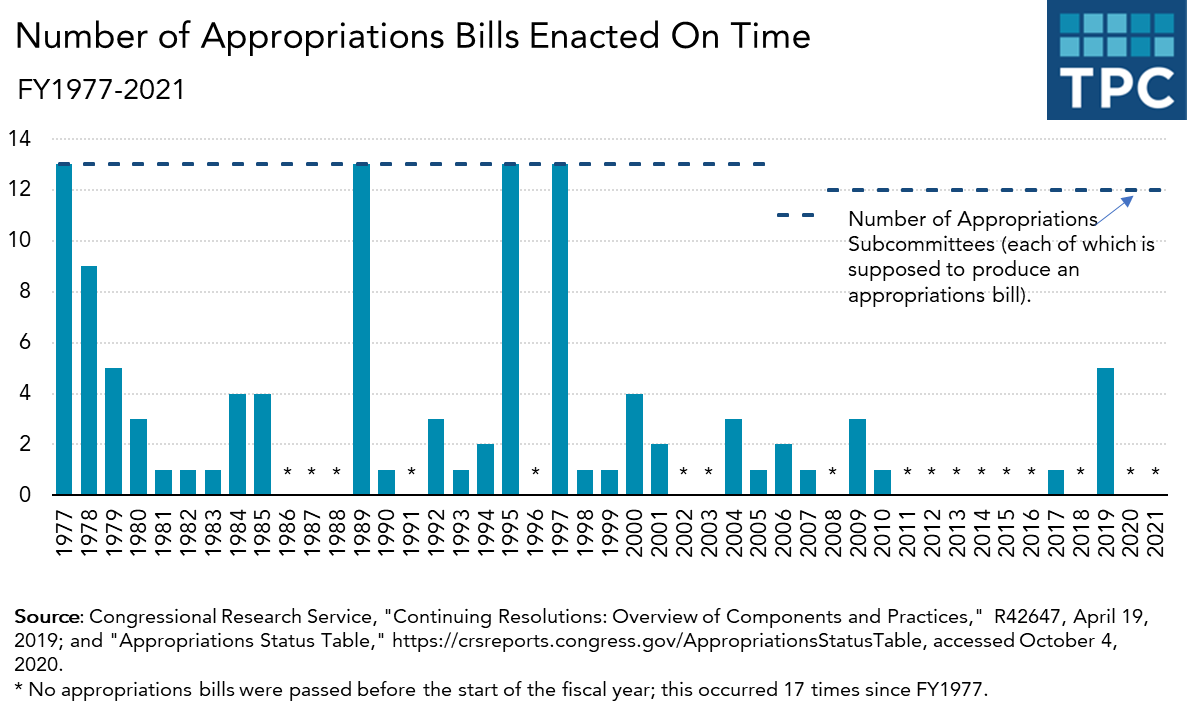

This failure of government was ignored because the federal budget process has been broken for decades. In 17 out of the last 46 years, the fiscal year has started with zero appropriations bills completed. Over that nearly half-century, Congress passed all its appropriations bills on time on only four occasions. The last time Congress did its job was 1997: Bill Clinton was president, the first Harry Potter book was published, and people were flocking to theaters to watch Titanic.

If we had higher standards for government performance, this level of incompetence would be a scandal.

CRs such as the one Trump signed are a terrible way to fund the federal government because they generally continue funding at prior year levels, with no regard to the value of the individual programs that are supported. They continue to fund those programs that have outlived their usefulness or badly need reform, and they fail to expand successful programs that need a boost. In other words, Congress fails to make any of the important budgeting decisions that are its job.

On occasion, CRs authorize and fund new spending. The fiscal year 2021 CR includes some new spending although most programs just continue to be funded at FY20 levels. But these new spending authorizations are also an abdication of the legislative process (and a violation of Senate rules). Appropriations bills are supposed to include only spending levels, not define government functions and outline how programs will operate, which happens in authorization bills. But some CRs have included more than 200 pages of legislative text. (See Table 5 of this handy CRS report.)

CRs not only avoid hard choices, but last-minute money bills—what fiscal expert Phil Joyce called “crisis budgeting”—are incredibly wasteful. It is extremely difficult for agencies and government contractors to plan and make hiring decisions when they don’t know their budget until after the fiscal year begins. It hurts employee morale and can cause agencies to lose their most productive employees (who have the best outside opportunities). Contractors incorporate the cost of uncertainty into their bids, raising government costs for obtaining goods and services.

It is even worse when budget inaction causes the government to shut down. The federal government has partially shuttered 18 times since 1976 because one or more appropriations bills were not signed in time. In 2018-19, the shutdown lasted 35 days.

The government also wastes money merely by preparing for and implementing shutdowns. As a funding lapse approaches, agencies start their shutdown procedures, which include things like securing facilities and recalling staff travelling on assignment. When agencies close, government contractors must stop all work and may not be able to pay their staffs. Essential programs may be suspended for days or weeks. Government employees are furloughed with no guarantee they will be paid. Even though they usually are fully compensated eventually, paying people not to work is the definition of waste. And shutting down national parks and monuments has ruined many family vacations.

This year, the House passed its appropriations bills months ago, but the Senate hasn’t taken up a single one. You might think the Senate majority would want to implement its spending priorities. The power of the purse is just as important as the power to confirm judges. And since those two activities are managed by different committees, a functional Senate should be able to do both at the same time.

A continuing resolution is a failure—not as big a fiasco as a government shutdown, but still a symptom of broken government. And we probably will get another CR when this one ends on December 11.

Is there a way to encourage legislators to do their jobs? Some would penalize Congress for failure, but it is highly unlikely lawmakers would legislate a penalty on themselves. Alternatively, lawmakers could get a hefty bonus if Congress does its job and completes all 12 appropriations bills before October 1. If behavior does not change, this option would cost the taxpayers nothing. But if the bonus nudged Congress to do its job, it would be a bargain.