As Congress debates whether to extend the major, but temporary, changes to the Child Tax Credit (CTC) it adopted earlier this year, a crucial question is whether it should keep the credit fully refundable.

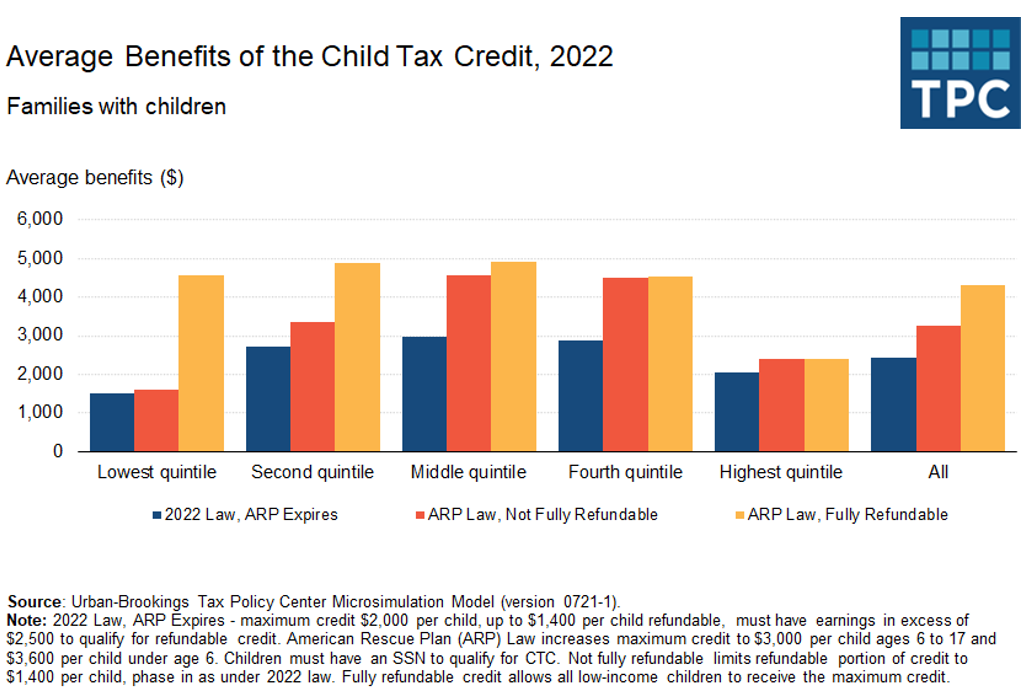

A new Tax Policy Center analysis finds that, for low-income families, full refundability is a key element of the CTC reforms. For families with children and incomes in the bottom one-fifth of the income distribution (income of $27,000 or less), keeping the higher credit amounts without full refundability would boost average benefits by only about $100 in 2022– from about $1,500 to $1,600. But if Congress also retains the law’s full refundability, average benefits for those families would almost triple relative to the prior law, to $4,600.

Benefits for families with children in the second income quintile (between $27,000 and $54,000) would rise by an average of almost $700 – from $2,700 to $3,400 – if credits amounts are kept at today’s levels but are only partially refundable just like before the temporary expansion. But their average credit would rise to almost $4,900 if both the higher amounts and full refundability continue. Retaining full refundability of the credit would make little difference for families in the highest two income quintiles.

In 2021, the American Rescue Plan (ARP) temporarily increased the credit from $2,000 per child under age 16 to $3,600 per child from birth to age 5 and $3,000 per child ages 6 to 17. And crucially, it made the credit fully refundable. Under prior law the credit was only partially refundable. The changes apply only for this year.

The Tax Policy Center analyzed three CTC variations: current 2022 law, where the ARP rules expire; extending ARP law including the higher credit amounts but without full refundability; and extending all of the CTC provisions of the ARP, including full refundability.

Of the total benefit delivered to families in 2022 if the ARP rules were kept in place, keeping the credit fully refundable would represent nearly a quarter of all benefits – almost all of which would be delivered to families in the bottom 40 percent of the income distribution.

A recent Urban Institute analysis finds that, in a typical year, extending the ARP provisions of the CTC would reduce poverty by roughly 40 percent – lifting 4.3 million children out of poverty. Maintaining full refundability is essential, however, to allowing the very lowest income families—those whose children are most likely to be in poverty— to receive the full value of the tax credit.

TPC estimates the child credit would deliver about $126 billion in benefits in 2022 if the ARP rules expire, about $169 billion if the credit amounts stay at ARP levels but are only partially refundable, and about $223 billion under all the ARP rules, including full refundability.

If Congress keeps full refundability but reduces credit amounts to pre-ARP levels, overall benefits would be lower. But low-income families would still receive substantial benefits if the lower credit amounts were made fully refundable.

Expanding the CTC to include even the very lowest income families was one of a package of changes that a panel of experts recommended to reduce childhood poverty. Failing to continue full CTC refundability would severely limit the credit’s ability to fight poverty, and again exclude millions of low-income children because their parents don’t earn enough. If policymakers are interested in fully using the CTC to reduce poverty, they should keep the credit fully refundable.