US taxation of intellectual property (IP) is facing big changes. Starting next year, research and development (R&D) expenditures, now fully expensed (written off in the year in which they are acquired), must be capitalized and amortized over a period of 5 to 15 years. Additionally, President Biden would repeal a special tax deduction for foreign-derived intangible income (FDII), offsetting the revenue gain with higher tax subsidies for investment in research and experimentation (R&E).

Capitalizing R&D would raise taxes on new research, while repealing FDII would raise taxes on existing profitable IP. However, FDII replacement (which could include retaining R&D expensing) could result in a net stimulus for new R&D.

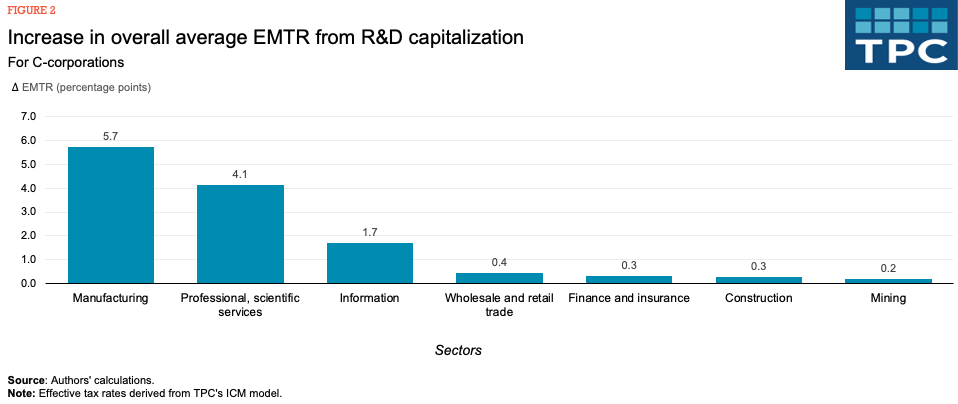

If Congress allows R&D expensing to expire as scheduled after 2021, the marginal tax rate on domestic research would increase by between 16 and 28 percentage points, depending on whether the investment also qualifies for the R&E tax credit. (While most R&D qualifies for expensing, the credit only applies to a fraction of expenditures.) This could trigger a decline in research that would hit the IP-intensive manufacturing and tech sectors particularly hard. The extent of the decline will depend on how sensitive marginal investment in R&D is to tax rates.

Research shows that R&D investment, the building block for IP, benefits the overall economy. Therefore, while financial accounting capitalizes R&D that creates long-lived assets, tax accounting has long been more generous. Congress allowed R&D expensing as early as 1954 and the R&E tax credit, which provides up to a 20 percent subsidy for increases in qualifying expenditures, was introduced in 1981. In fiscal 2021, the two subsidies combined cost the Treasury about $22 billion in lost revenue.

Congress extended the cost recovery period for R&D in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) to help pay for other tax cuts. Unless the law is changed, starting in January firms must amortize their domestic R&D in equal annual amounts over 5 years and foreign R&D over 15 years. The congressional Joint Committee on Taxation estimates this measure will raise $120 billion between 2022 and 2027.

However, the House Ways and Means reconciliation bill would retain R&D expensing until 2025.

TCJA also introduced the FDII regime, which reduced corporate tax rates to 13.125 percent for export-related domestic profits that exceed normal returns, or “rents”. Together with the TCJA’s global intangible low-income (GILTI) provisions, FDII was enacted to encourage US multinationals to repatriate IP held offshore.

These incentives appear to have been at least somewhat successful: According to Tax Notes columnist Marty Sullivan, the domestic share of worldwide profit for 20 large US tech companies increased from around 32 percent in 2017 to more than 55 percent in 2020, driven largely by IP repatriation.

R&D capitalization and FDII offer opposing incentives for IP and have very different marginal effects. Expensing, like the R&E tax credit, encourages new investment. By contrast, the reduced tax rate offered by FDII mainly benefits existing profitable IP assets. Thus, R&D expensing and tax credits are more effective at stimulating the investment that generates economic growth.

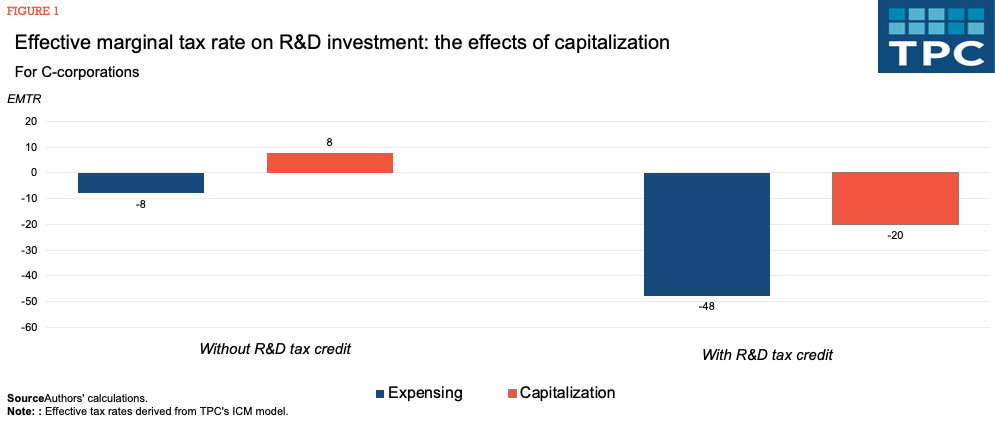

To measure the impact of capitalization , we used TPC’s Investment and Capital Model to calculate effective marginal tax rates (EMTRs) on R&D. EMTRs measure the “tax wedge” between the pre-tax and after-tax returns for an investment that just breaks even after taxes, as a percentage of the pre-tax return.

For an investment that does not receive the R&E tax credit, capitalization raises the corporate EMTR from -8 percent to 8 percent. This increases the present-value cost of an additional dollar of R&D investment from $0.92 to $1.08 – about 17 percent. For an investment that receives the tax credit, the EMTR increases from -48 percent to -20 percent, while the cost rises by 54 percent, from $0.52 to $0.80.

Manufacturing would face the greatest increase in its overall average EMTR. Our estimates assume an average effective R&E tax credit rate of 6.2 percent (based on SOI data) and an average debt weighting of 40 percent. They also include only corporate-level taxes, not investor-level taxes on dividends, capital gains or interest.

Research shows the short-run price elasticity of R&D spending (the percentage change in spending relative to a percentage change in its cost) is around -1. In the long run, the elasticity is at least twice as large. This indicates that capitalization could reduce marginal R&D spending by up to 65 percent in the short run, and even more long-term.

Capitalizing R&D could significantly reduce IP investment. To avoid this, Congress is likely to extend the current expensing rules. But it still is a good time to evaluate the fiscal and economic effects of tax subsidies for research, focusing on the relative benefits of tax incentives for investment and those for rents.