The child tax credit (CTC) provides a credit of up to $2,000 per child for families with children under 17. But low-income families often get much less than that because only a portion of the credit is refundable to taxpayers who have little or no income tax liability. Policymakers could make a few relatively minor changes to the credit that would direct more resources to those families with the highest needs—something research shows could help families now and also provide long lasting improvements in health and education outcomes.

Annually, the CTC delivers about $130 billion in benefits to families with children. This includes the CTC available for families with children under 17 as well as a $500 nonrefundable credit available for older children and other dependents. Families in the lowest-income quintile receive the lowest average benefit from the CTC – about half that received by all but the highest income families. The $500 credit for older dependents comprises a small share of the total CTC, so the remainder of this post focuses on the portion of the credit for children under 17.

Why do the lowest income families receive the lowest benefits? Because families calculate their CTC by first using it to offset income taxes owed. If the credit exceeds taxes owed – which it often will for low-income families, taxpayers can receive up to $1,400 of the balance as a refund, known as the additional child tax credit (ACTC) or refundable CTC. The ACTC is limited to 15 percent of earnings above $2,500. Limiting the credit to earnings above a threshold and limiting the amount of credit that can be refunded both work to reduce the credit available for low-income families. At relatively modest cost, Congress could increase the credit for low-income families with children under 17 by:

- allowing all earnings to be used to calculate the amount of the credit, not just earnings in excess of $2,500 (which would increase credits in FY 2020 by $2 billion);

- allowing families to receive the full $2,000 credit as a refund, rather than limiting the refundable portion to $1,400 (which would increase credits in FY 2020 by $6.8 billion); or

- phasing the refundable portion of the credit in faster (for example, at a rate of 45 percent instead of the current law 15 percent) so that families would need to earn less to qualify for the full refundable credit (which would increase credits in FY 2020 by $5.5 billion).

Enacting all three of these fixes would cost about $21 billion in 2019.

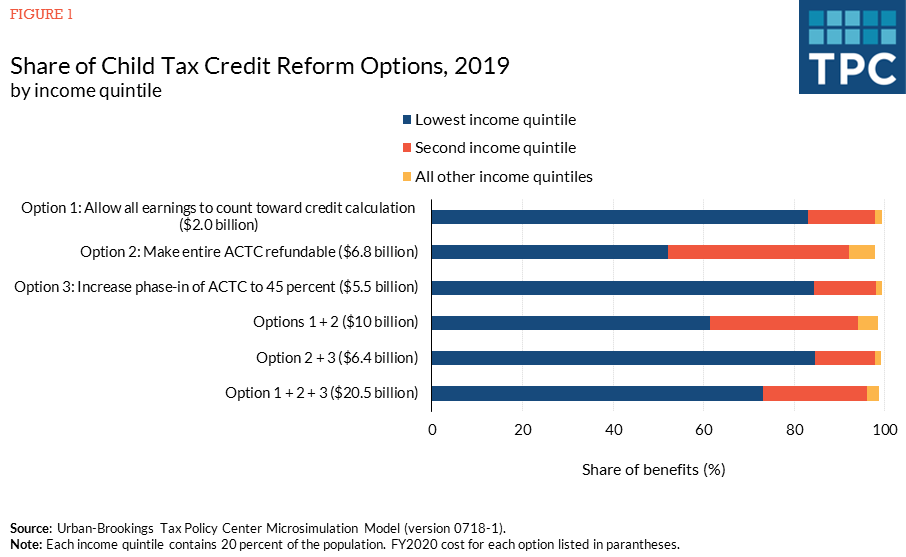

Among families with children, benefits from any of these proposals would be heavily tilted toward those in the bottom 40 percent of the income distribution; over 80 percent of benefits from allowing all earnings to count toward the refundable portion of the credit or phasing the refundable portion of the credit in faster would accrue to families in the lowest 20 percent of the income distribution (figure 1).

For families with children who would benefit from the options, the average credit increase for each option would be highest for those in the lowest 20 percent of the income distribution (figure 2).

Amending the CTC to allow all earnings to count toward the credit’s calculation, allowing the full $2,000 credit to be refunded, or phasing in the credit faster would largely assist the lowest-income families with children, without raising the overall cost of the credit unduly. Doing so would not only help low-income families meet existing needs, but could also improve health and education outcomes later. And this seems like it would be money well spent.