Cities, counties, and other local governments have traditionally relied on property taxes as a substantial and stable revenue stream. But with remote work taking hold after the pandemic, studies suggest that the value of office buildings could fall by half in many cities. The question facing policymakers is not if this will affect local budgets but how bad will it get.

In a new analysis, we analyzed how dependent 47 major cities are on commercial property tax revenue. And, combining those data with an estimate of future office values, we made two forecasts of revenue shortfalls by 2031 in 13 cities for which complete data were available.

The forecasts show the severity of the revenue shortfalls were large in some cities but relatively manageable in others. But some cities also saw large swings in the projected shortfalls under the different forecasts, highlighting important questions for policymakers to ask about their specific fiscal futures.

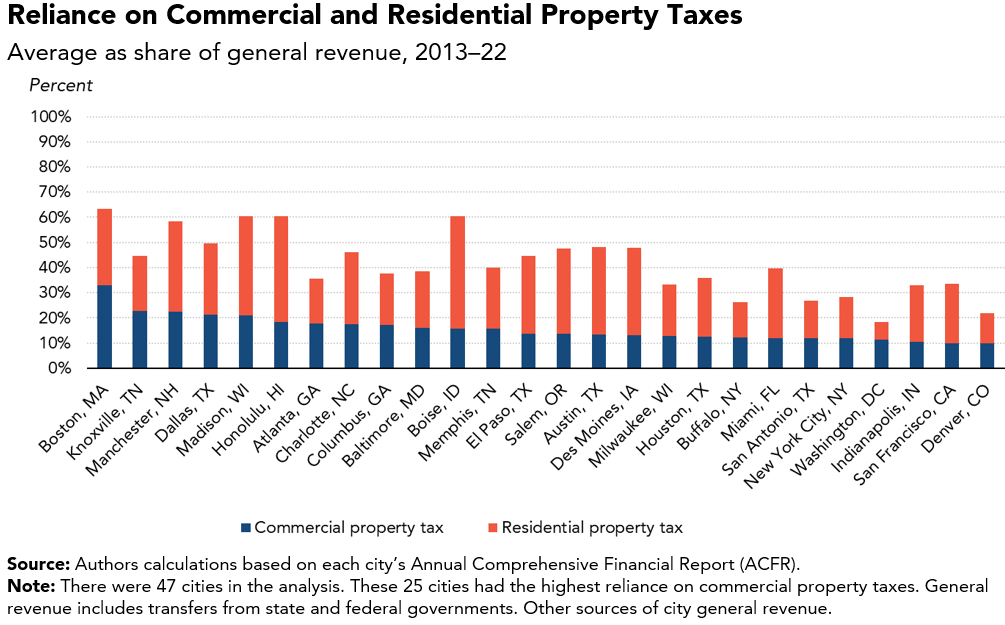

How commercial property tax dependence varies across cities

In the post-pandemic economy, a high reliance on property taxes does not necessarily spell trouble for local budgets because residential home values have soared over the past few years. But some cities stand out for their reliance on commercial property tax collections, and thus possible risks for their future budgets.

For example, in our data, Boise had one of the highest dependencies on the property tax overall, but its reliance on commercial property taxes was not in the top 10. In contrast, Atlanta did not have one of the highest reliance on overall property tax collections, but its dependence on commercial property tax revenue was the seventh highest in our dataset. This divergence can result from the underlying value of the properties in the city or the way the city assesses and taxes these different types of property.

Overall, in the 47 cities we studied, the highest commercial property tax revenue reliance was in Boston, Knoxville, Manchester, and Dallas. In each city the commercial property tax accounted for 20 percent or more of general revenue. See the full report for detailed data on all 47 cities.

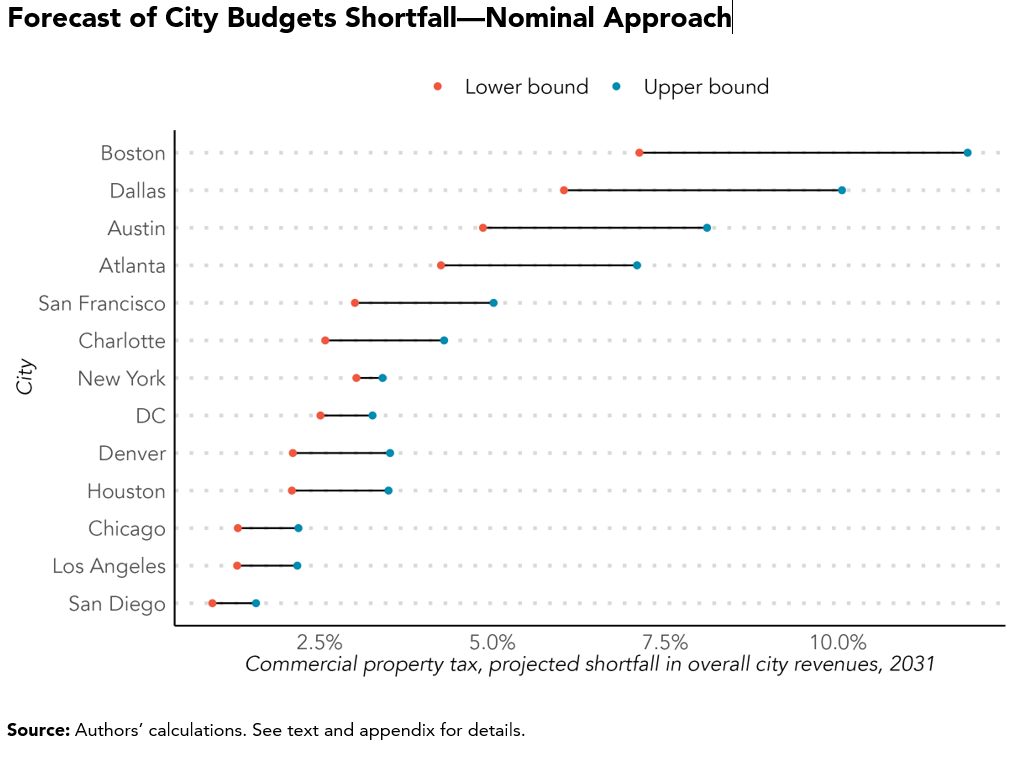

Forecast based on declines in commercial property values

In our first forecast, we compared projected post-pandemic declines to an alternative where office buildings grew in value between 2022 and 2031 at the same rate they did over the previous decade.

The result was a shortfall of 2.5 to 3.5 percent of total revenue in 2031 in our median city. (We present a range because a major unknown is the share office buildings in each city.) Notably, while a 2.5 percent drop might not sound large, it represents hundreds of millions of dollars and could force either large tax increases or spending cuts to balance a city’s budget.

The most at-risk cities under this forecast were cities that either relied heavily on commercial property tax revenue pre-pandemic (Boston) or had particularly strong commercial property value growth over the previous decade (Austin). Alternatively, cities at the lower end of the forecast (San Diego) mostly had a relatively low reliance on commercial property tax revenue.

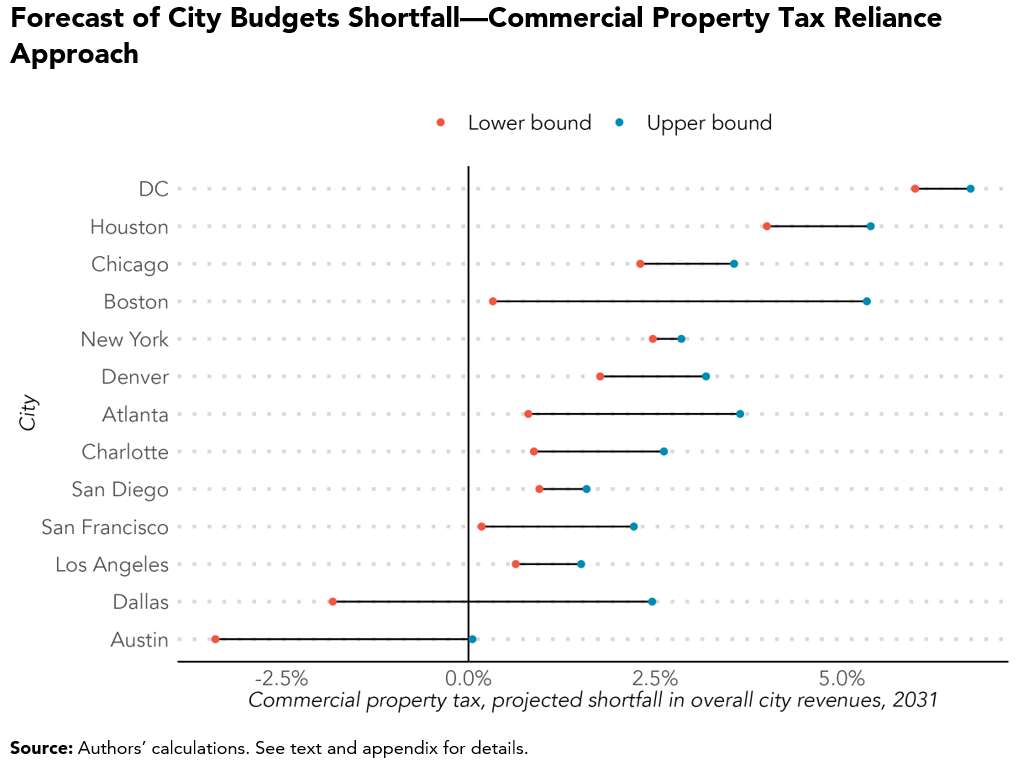

Forecast based on the share of commercial property tax revenue in the budget

Our second forecasts asked a different question: How much revenue from other sources would a city need to raise to fund its expected 2031 expenditures in the new reality of declining commercial property tax collections? In other words, what is the shortfall if values drop but commercial property tax reliance does not? In this forecast, the median city saw an overall shortfall of 0.9 to 3.2 percent.

Framed this way, the District of Columbia sees the largest shortfall, mostly because of its recent revenue and spending trends. That is, the District’s pre-pandemic fiscal path relied on the commercial property tax propping up relatively elevated spending levels, and growth rate of spending over the past decade was larger than the growth rate of commercial property taxes. With commercial values now forecast to drop, it must find other significant revenue sources or cut spending. Houston and Chicago face a similar issue.

In contrast, Austin and Dallas could see no overall revenue shortfall in this forecast because their commercial and residential property taxes grew much faster than spending over the previous decade. As a result, those cities need a much lower growth rate in commercial property taxes to maintain their current reliance.

Importantly, both forecasts assume that other types of commercial real estate (e.g., retail and industrial buildings) keep growing in value. If these other types of commercial property also see declines in value, then these projected shortfalls could be even larger.

Across local governments, policymakers should pay close attention to their government’s reliance on commercial property taxes and how this aligns with their other fiscal trends. If other sources of revenues are expected to grow, a city may see little budget impact from falling commercial values. However, if a government’s expenditures are premised on strong commercial property tax collections, policymakers may face big budget questions over the next few years.

Unfortunately, there are no simple budget solutions to falling office values. But an important first step is understanding mechanics of commercial property tax collection and why different cities could face very different fiscal futures.