Momentum behind a tax plan drafted by Senate Finance Committee Chair Ron Wyden (D-OR) and House Ways and Means Committee Chair Jason Smith (R-MO) has restarted a debate about whether a more generous child tax credit (CTC) would prompt people to leave the workforce. Some of these claims lack context that both policymakers and taxpayers should understand.

The Wall Street Journal, in an editorial last week, blasted the CTC portion of the Wyden-Smith tax legislation, citing numbers from a new American Enterprise Institute study. That report suggests part of the CTC proposal could prompt hundreds of thousands of parents to stop working, thus offsetting the economic benefits of some parents who would start working because of the program changes and of reducing poverty among the least well-off families.

Would CTC changes in the Wyden-Smith bill result in a noticeable change in work choices, though? A review of the evidence suggests the issue is complicated, given there are several ways in which the bill could actually strengthen the CTC’s work incentives.

Differing incentives

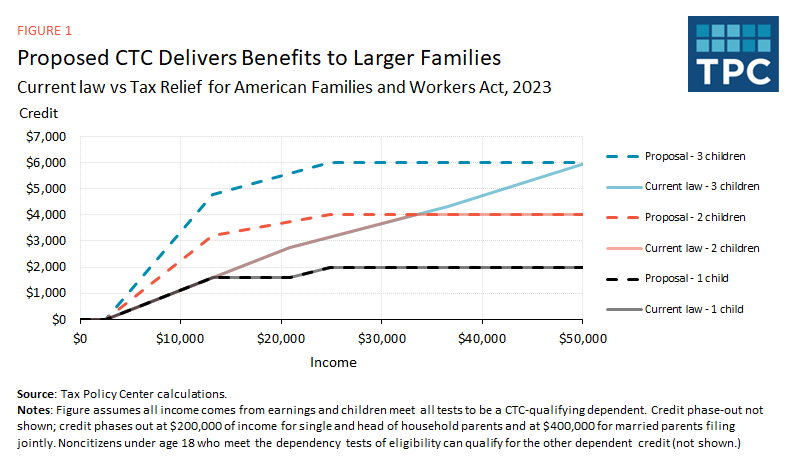

First, let’s review the proposal. The current CTC offers a tax break of up to $2,000 per child (of which up to $1,600 available can be available as a tax refund in excess of taxes due). The refundable portion of the credit phases in at a 15-percent rate with each dollar a taxpayer earns above $2,500 annually.

The Wyden-Smith proposal would leave in place the $2,500 income threshold before earnings start counting toward CTC benefits. The bill would phase the credit in faster for families with more than one eligible child: at a 30-percent rate for two children, 45-percent for three, and so on. It would also gradually increase the maximum refundable credit so that by 2025, low-income families with sufficient earnings could receive the full credit as a tax refund.

By contrast, the current credit phases in at the same rate for all households regardless of size. As a result, some low-income families’ CTC benefits don’t reflect the increased costs of raising multiple children. Figure 1 below illustrates how the current credit phase-in compares to the Wyden-Smith proposal.

This policy change, in isolation, would increase the incentive to work among eligible recipients with multiple kids. Economists Hilary Hoynes, Jesse Rothstein, and Krista Ruffini, summarizing the research on the earned income tax credit (EITC), explain why, citing “robust evidence that the EITC succeeds in increasing [labor force participation], particularly among low-educated women and those workers with multiple children.”

The Wyden-Smith plan would also allow taxpayers, starting in 2024, the option of using the prior year’s income to determine their benefits when filing taxes. Going back to our household with three kids and $20,000 in income, under the “lookback” provision they could work in 2024 but then quit the labor force entirely in 2025, while still getting the same CTC benefits in 2025.

The AEI study says the lookback could cause as many as 700,000 people to leave the workforce every other year (the study notes that other provisions, like the increased incentive for non-workers to join the workforce, could lower that number to a net loss of 150,000 workers on average every year). While in principle this is possible, it’s highly unlikely.

For one, the proposal as a whole, and the lookback provision itself,would both increase and decrease the incentive to work for different households, as noted elsewhere. If our same sample family of three didn’t normally work, they could receive two years of CTC benefits from working for at least one year. In this hypothetical case, returning to work would be more beneficial under the Wyden-Smith lookback provision.

Second, financial planning is quite difficult for lower-income families. Many of those households already have volatile income streams making it difficult to predict changes in their tax benefits, further amplifying their income swings. In fact, the family in our example would also lose EITC benefits (around $4,000 for a family with one child, or $7,500 for a family with three or more children) in addition to forgoing their labor income by not working. Juggling this and figuring out a way to move in and out of the workforce each year would be a serious financial challenge.

Bottom line: Families’ decisions around work are ultimately complicated by other factors, including needing to leave the workforce because of raising a child. As another AEI researcher, Kyle Pomerleau, explained, “This expansion will increase work incentives for some and reduce them for others, but overall, there is little reason to be concerned about a large reduction in labor supply.”

Gathering more evidence

The complaints about the CTC discouraging work arose with the 2021 American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA). ARPA raised the CTC to a maximum of $3,600 per child under 6 years of age (and $3,000 for children under the age of 18) and made it fully refundable in 2021, meaning eligible households could get the full benefit, regardless of income.

Evidence thus far suggests that the 2021 CTC did not prompt major changes in labor force choices among recipients. However, the credit was only in place for one year because efforts to extend the ARPA version fell short. That was one reason CTC expansion critics at the time cautioned that data from 2021 should be reviewed carefully before jumping to conclusions.

Should the Wyden-Smith CTC proposal pass Congress, it’s primarily a bridge to the looming 2025 tax debate. After that year, the individual income tax changes—including adjustments to the CTC—will expire. But whether we’re debating temporary or permanent policy, there are indeed tradeoffs involved in any reform of the tax code. Measuring whether people could leave the workforce is worth consideration, but so are the potential reductions in child poverty and gains in financial flexibility for those with the lowest incomes.