The 50 states are diverse, but in the COVID-19 pandemic era, they share a key challenge: An economic and fiscal crisis of a size and speed not seen since the Great Depression.

According to new Bureau of Labor Statistics data, April unemployment rates ranged from 7.9 percent in Connecticut to 28.2 percent in Nevada (find and graph your state’s data here). The biggest increases in unemployment rates from February to April were in Nevada (up 24.6 points), Hawaii (up 19.6 points), and Michigan (up 19.1 points). Given what we know about unemployment rates and state tax revenue, the budgetary fallout will be catastrophic. And it will play out over years, not months.

The first place where you might look for tax trouble are states that rely heavily on individual income taxes, the revenues from which tend to rise and fall with the economy.

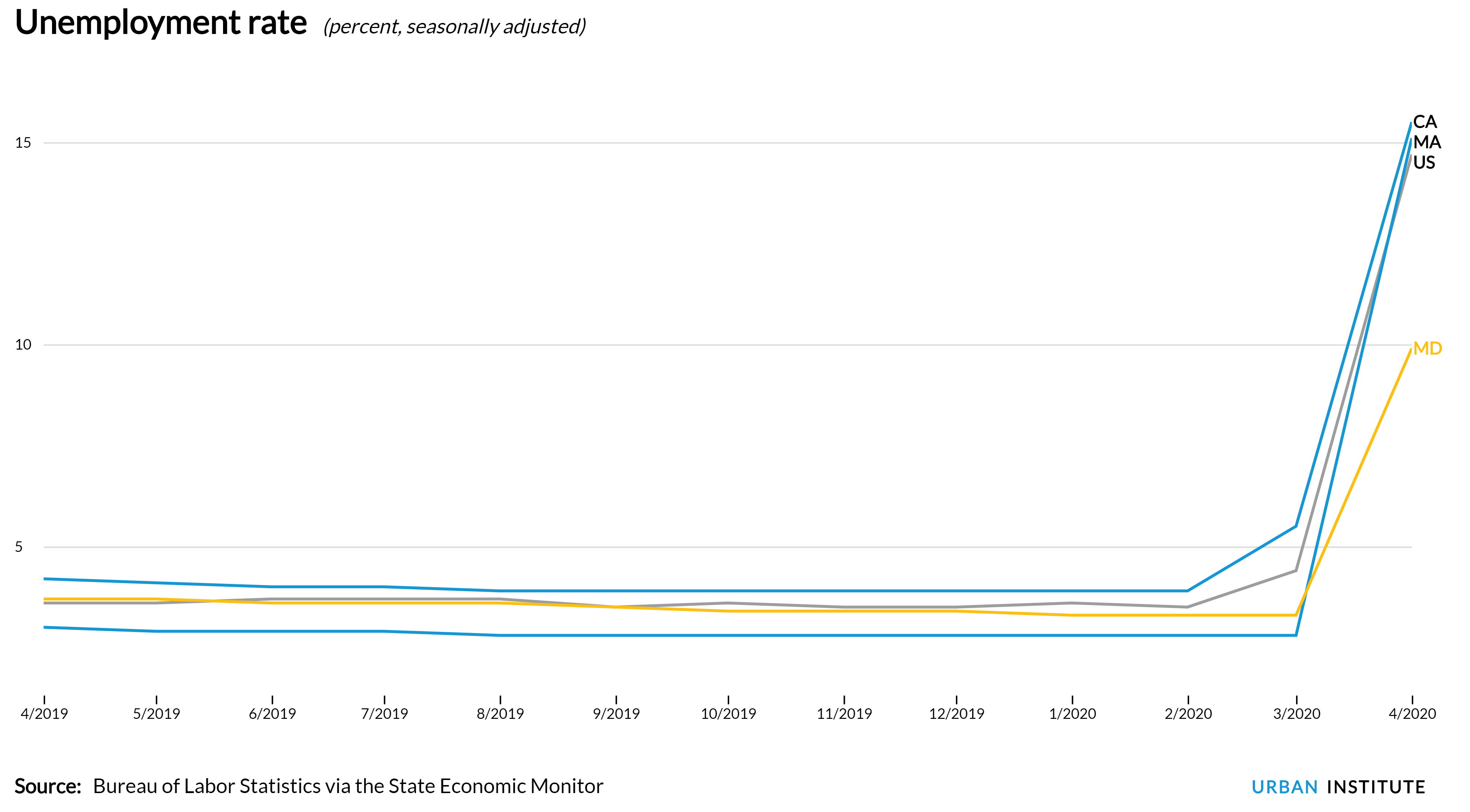

Maryland is the most dependent on individual income tax revenue, where the tax accounts for nearly a quarter of its state and local general revenue. The income tax produces nearly 20 percent of state and local general revenue in Connecticut, California, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New York, and Oregon. The US average is 12 percent.

Maryland saw its unemployment rate rise from 3.3 percent in February to 9.9 percent in April. This was one of the smaller jumps in unemployment (if you can call an increase of six percentage points in two months “small”), and much less than the spikes in other income tax dependent states like California (unemployment at 15.5 percent) and Massachusetts (unemployment at 15.1 percent).

Still, Maryland’s fiscal picture is bleak. The state expects to lose about $300 million in income tax revenue in the fiscal year that ends on June 30, $1.6 billion in the following year, and another $2.5 billion in the year after that. This is roughly 15 to 20 percent lower than the state expected to collect in income taxes before the pandemic. And none of these totals includes local income taxes, which also are a large source of revenue in Maryland.

But income taxes are far from the only revenue source hurt by high unemployment.

National retail sales fell 16.4 percent from March to April, taking general sales tax revenue with it. And even when state economies “open up,” it may take some time for consumption to return, either because people fear going out to shop, are unemployed, or worry about losing their job.

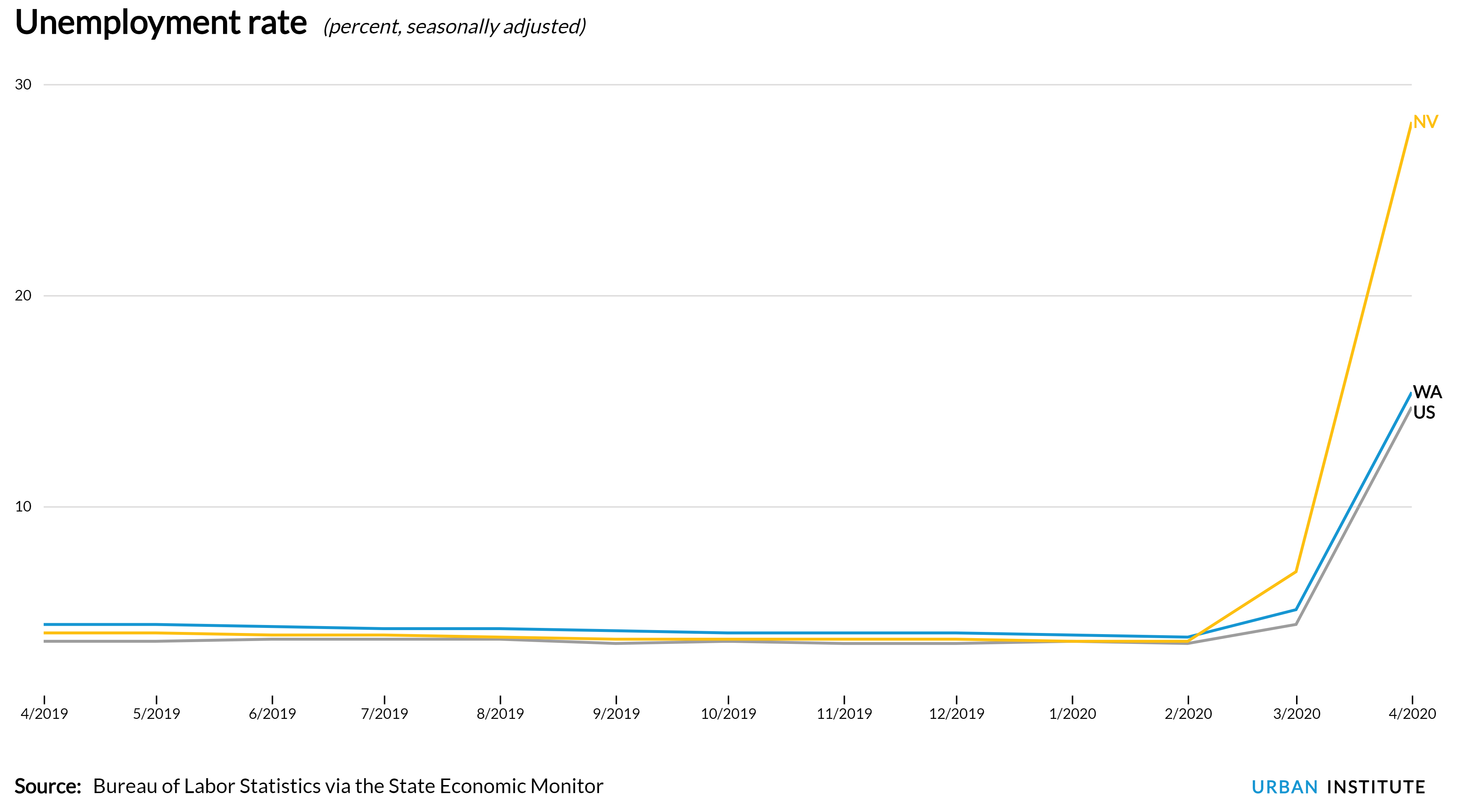

States most dependent on sales tax revenue include Arizona, Hawaii, Louisiana, Nevada, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Washington. Each collects a fifth or more of their state and local general revenue from general sales taxes, nearly twice the US average of 12 percent.

Nevada (unemployment at 28.2 percent) and Washington (unemployment at 15.4 percent) are the two states most reliant on sales taxes. They also saw two of the highest jumps in unemployment from February to April.

Nevada is bracing for its largest budget deficit ever. Washington expects a possible $7 billion loss over three years. These estimates also exclude local taxes. Across the country, the National League of Cities estimates total municipal revenues will drop 20 percent this year.

Only Alaska, New Hampshire, and Wyoming don’t rely heavily income or sales taxes, but these three states also face devastating revenue shortfalls.

Alaska (unemployment at 12.9 percent) and Wyoming (unemployment at 9.2 percent) rely heavily on severance taxes on mining, oil production, and the like. But those revenues collapsed with the price of oil. As a result, the budget picture in Alaska, Wyoming, and other energy-reliant states may be even more dire than in states that rely on income or sales taxes.

New Hampshire (unemployment at 16.3 percent) depends heavily on local property taxes. Typically, property taxes are a more stable source of revenue, even in a downturn. But with so many people out of work and businesses without customers, local governments in New Hampshire (and across the country) fear that unprecedented numbers of people will delay or miss property tax payments.

Plunging revenues, driven in large part by record high unemployment, combined with state balanced budget rules, are why Congress needs to support state and local governments—and fast. Without that support, state and local governments will be forced to lay off more workers, adding to the unemployment catastrophe.

You can divide states in all sorts of ways—rich and poor, red and blue, income tax and sales tax. But none will avoid the high fiscal cost of the COVID-19 pandemic.