Republican and Democratic presidential candidates have a decades-long history of pledging to cut or not raise taxes for at least some income groups. In 2016, Republican Donald Trump pledged to reduce taxes for the middle class, while Democrat Hillary Clinton pledged not to raise taxes on individuals earning less than $250,000. In 2020, Democrat Joe Biden pledged not to raise taxes on anyone making less than $400,000, a promise Democrat Kamala Harris re-affirmed this summer.

Candidates promise to insulate “middle-class” households (and voters) from tax increases. But these income-specific, no-tax pledges complicate the tax code and hamper efforts at reform. To show how we used the Tax Policy Center’s microsimulation model to simulate several different policy scenarios. (A fuller discussion of our methodology is available in our new paper.)

To start, we estimate a baseline where federal tax receipts will total $4.8 trillion and the average household will pay 19.8 percent of their income in taxes in 2025. We then simulate a 10 percent tax increase under five different income-specific, no-tax-increase thresholds: $0 (or no threshold), $100,000, $250,000, $400,000, and $1,000,000.

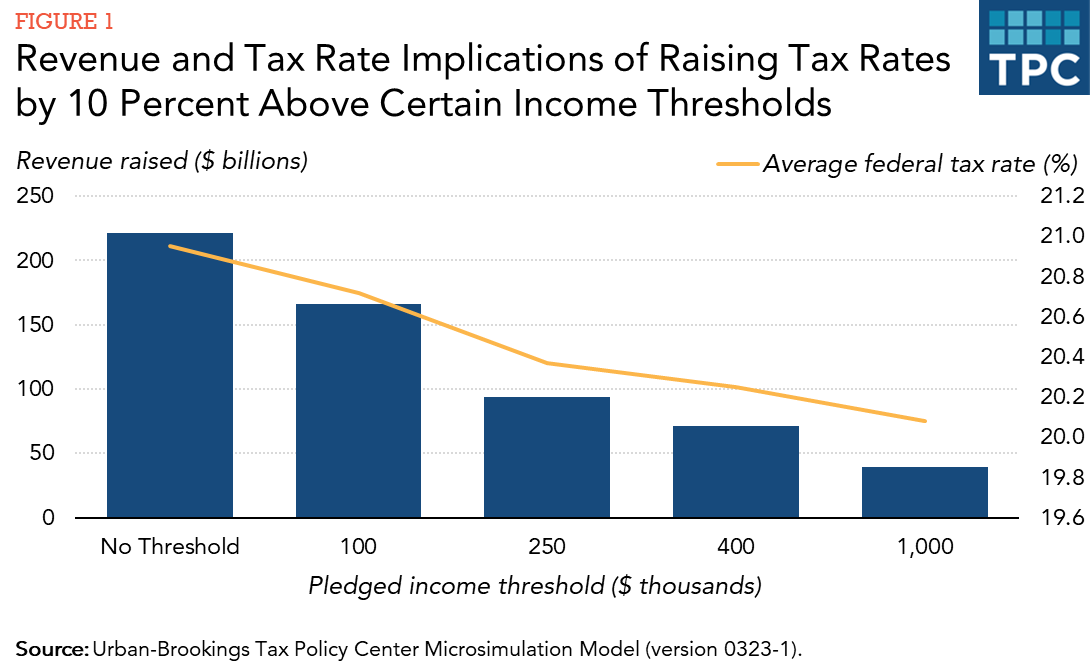

With no threshold, a 10 percent rate increase would apply to all tax brackets and raise $221 billion in additional tax revenue in 2025. The average federal tax rate would increase by 1.1 percentage points. But, as income thresholds for holding taxpayers harmless climb, that projected revenue gain declines (Figure 1).

For example, with a no-tax-increase-below-$100,000 threshold, a 10 percent rate increase would raise $166 billion. But under a $400,000 pledge, the rate change would raise only $71 billion, and under a $1 million pledge, the rate change would raise just $39.4 billion.

The steep decline in revenue reflects the fact that each increase in the threshold eliminates a larger share of taxpayers, and therefore income, from the tax base. For example, the $400,000 threshold excludes more than 95 percent of tax units.

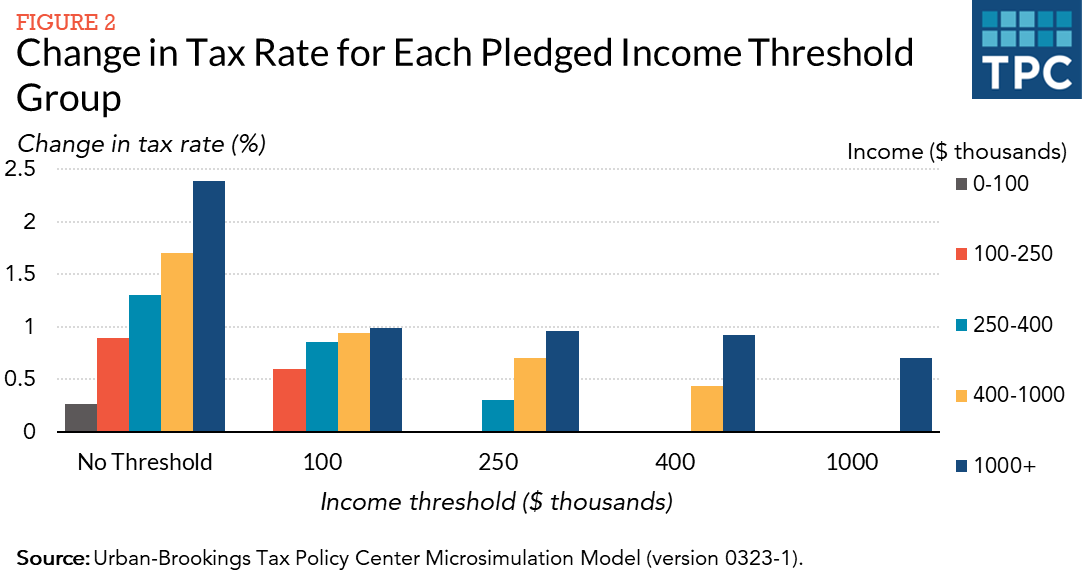

Figure 2 shows how average tax rates change for taxpayers in each income group as the threshold pledge increases. With no income threshold, the tax code’s existing progressivity remains: With a 10% tax rate increase, the average tax rate increases by just 0.3 percentage points for households earning less than $100,000 and climbs steadily to 2.4 percentage points for households earning more than $1 million.

As the income no-tax-pledge threshold rises, the average tax rate for households under the threshold falls. For example, if the threshold were $100,000, the increase in the average tax rate of those earning $100,000 or less would be 0.5 percentage points, a 44 percent reduction compared to the 0.9 percentage point change under a no-threshold policy. Likewise, with a $400,000 threshold, the increase in the average tax rate for households earning between $400,000 and $1 million would fall from 1.7 to 0.7 percentage points, or a 58 percent reduction.

But the groups who benefit the most from higher thresholds aren’t always the taxpayers that a pledge targets. This diminishes the progressivity of the tax code. For instance, when the no-tax income threshold climbs from $250,000 to $400,000, taxpayers in that income group avoid a 0.4 percentage point increase in their tax burden (saving $6.4 billion). But taxpayers earning between $400,000 and $1,000,000 save even more (0.5 percentage points or $13.3 billion).

Because of how average and marginal tax rates work, taxpayers earning more than $400,000 avoid tax increases on their share of income under the threshold, or between $250,000 and $400,000 in this case.

This feature of the tax code will make the work of the next Congress and presidential administration harder as they determine whether and how to extend the TCJA, which the Congressional Budget Office and Joint Committee on Taxation estimate would cost nearly $5 trillion (including additional interest on the debt) over ten years.

Some have proposed an extension of the TCJA that maintains individual income tax cuts only for households under $400,000. But that pledge runs into problems just like the ones modeled in our paper. It risks introducing further complexities and behavioral distortions that run counter to optimal tax policy. And, these make it more difficult to implement important reforms, like those for Social Security and paid family leave, because funding these reforms would likely not be pledge-compliant.

This is no small problem for a federal government already struggling with debt. While middle-class tax pledges may be good politics, they’re bad for our tax code and fiscal health.