This week, the Treasury Department finalized the last set of Obama-era regulations intended to curb tax-motivated corporate inversions. An inversion arises when a U.S. corporation either creates a foreign corporation to be its new parent or merges into a smaller existing foreign corporation. After the inversion, the combined firm can lower its U.S. tax bill by shifting profits abroad, either through inter-corporate transactions or increased operations abroad. A variety of other regulatory rules, also implemented during the Obama years, now discourage inversions.

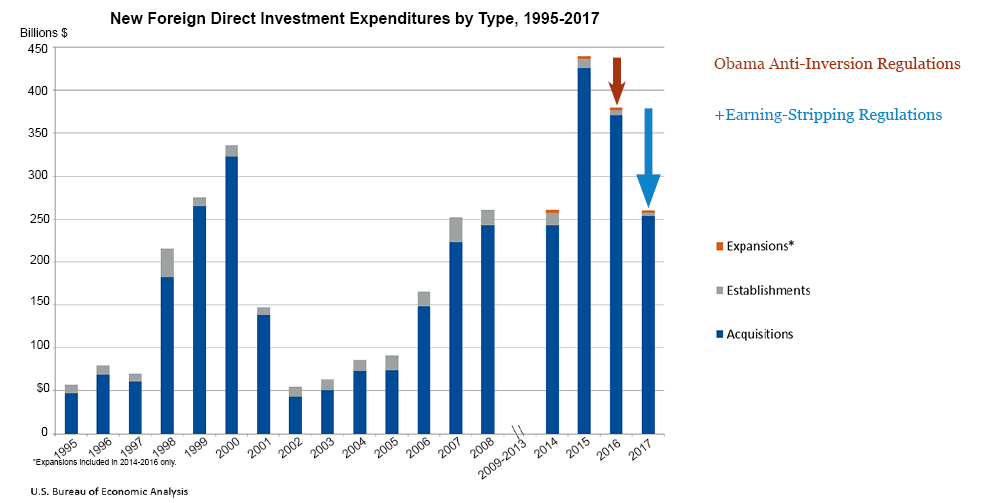

Coincidentally, the Commerce Department released new data on foreign direct investment in U.S. businesses, which indicates that Obama’s anti-inversion rules sharply reduced tax-motivated acquisitions of U.S. firms by foreign companies.

The chart above shows a large increase in foreign direct investment in 2015. The Commerce Department estimated that newly inverted U.S. corporations accounted for a significant share of foreign direct investment in 2015 (20 percent), but not in 2016 or 2017. The 2015 spike also reflected a greater number of foreign corporations acquiring smaller U.S. corporations and combinations of equal-sized companies.

All of these combinations allowed companies to reduce their aggregate income tax liability using intercompany “debt.” In these earnings stripping transactions, the U.S. firm did not actually borrow any money from an outside party—it just distributed a note to its foreign parent and made interest payments to the parent firm. The interest was deductible against U.S. earnings and taxable to the foreign corporation. As a result, the arrangement effectively shifted taxable earnings from the U.S. to its parent’s home country, which generally had a lower tax rate. The U.S. firm might still pay some U.S. income tax, but it could reduce its bill by appearing to borrow from its foreign parent. And the company as a whole would reduce its worldwide taxes paid.

The Obama Administration effectively ended this practice with earning-stripping regulations in 2016. Now, the Trump Administration is being urged to revoke those rules. One argument: Because the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) sharply lowered U.S. corporate tax rates to levels much closer to those of many other developed countries, there is less need for regulations to bar earnings stripping.

However, notwithstanding the changes contained in the TCJA, revoking Obama’s earnings-stripping regulations could re-invite corporate tax abuse, an issue I will address in an upcoming blog.