The U.S. recently surpassed the unfortunate milestone where all new federal revenue is already committed to specific spending priorities due to existing laws. As discussed in my recent book, Beyond Zombie Rule: Reclaiming Fiscal Sanity in a Broken Congress, this obstruction of current and future voters’ ability to make decisions has been growing under all recent presidents. That growth shows no sign of abating under President Trump.

Unless Congress enacts major reform, this extraordinary constraint will block any significant effort by President Trump and a Republican Congress—or any future Democratic majority—to alter the long-term course cemented by those past legislators. Like zombies, past legislation rises up and drags revenues away from funding today’s and tomorrow’s priorities.

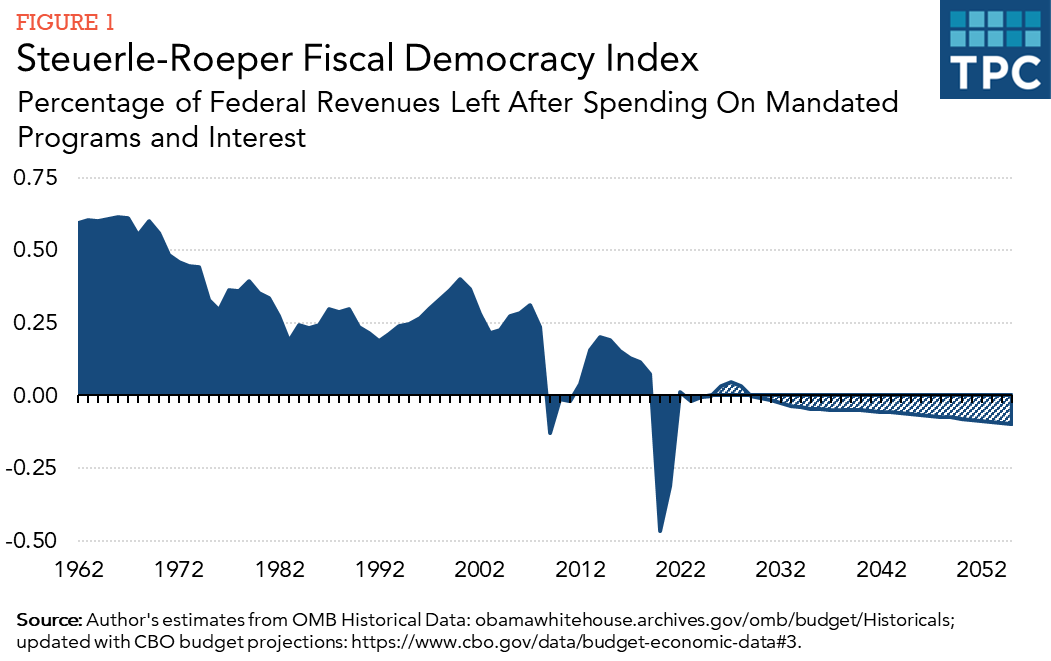

To show how the nation’s tax and spending laws have combined to restrict the choices of succeeding generations, Tim Roeper, now with the Department of Economics at New York University, and I developed a fiscal democracy index. The index (Figure 1) simply measures the share of available federal revenues in any year, after paying for mandated programs — the largest are Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid— and interest on the debt. Both automatic spending growth built into law and new tax cuts not offset by other tax increases or spending reductions cause the index to fall. The projections are based on what current law, as interpreted by the Congressional Budget Office, commands.

Throughout most of the 1960s, the index stood at over 60 percent; by the mid-1970s to 2000, it was between 20 and 40 percent; today, at a time of full employment, it is essentially zero.

Absent changes to current law, the index will continue to fall deeply and permanently into negative territory based on data from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). Furthermore, CBO presumes that Congress will fund new giveaways not yet in the law. Consider this: Since the start of the century, we’ve experienced three major emergencies—9/11, the Great Recession, and COVID-19. Their fiscal consequences are reflected by downward spikes in the figure. None of these emergencies was paid for, adding trillions of dollars to the federal debt.

Compare the current period to the one after World War II when the debt level was similar to today’s as a percentage of national income. During that time, very little spending was mandated. For many years, Congress could approve many new tax reductions and spending increases simply by allocating available revenues that flowed into the government, thanks mainly to economic growth.

We have faced significant debt issues in the past, but the increasingly unchecked erosion of democratic decision-making over decades represents a completely different situation.

The nation tries today, as it has in every era, to adapt to contemporary needs. It doesn’t matter whether citizens support more spending for defense or the working class, lower taxes, or addressing whatever challenges the next emergency or opportunity may present. Whatever elected officials want to achieve, they are trapped: They can steer the nation in a new direction only if they break past promises of low taxes and high automatic growth rates in existing programs.

The collapse of fiscal democracy explains much of the chaos surrounding recent Congresses.

The Madisonian system of checks and balances embedded in the Constitution has been completely inverted. Throughout most of the nation’s history, increasing spending required a type of supermajority support from both chambers of Congress and the President. Today, restraining or paying for the automatic and nearly limitless growth now ingrained in existing programs requires the same supermajority.

Deficit reduction alone is not sufficient to restore fiscal democracy. If it’s done mainly with cuts in discretionary spending, mandated spending could still absorb all or almost all of the revenue boosted by economic growth. The zombies would still rule.

Fiscal democracy can be restored only through major budget reform. While a dramatic change from our current situation, it would hardly be revolutionary to reinstate what was common to almost all federal budgets throughout the nation’s history.

Elected representatives must be able to allocate for current use some, all, or more than all of the revenue increases arising from economic growth. Congress could then make choices to maximize today’s and tomorrow’s opportunities, rather than solve yesterday’s problems.