The recent oil price spike has triggered many calls for a temporary windfall profit tax (WPT) on the oil industry, which the US last imposed in the 1980s. But the ideas now on the table are quite different from one another.

Properly designed, a tax on excess profits – or “rents” – from petroleum production can be a highly efficient and progressive way to raise revenue. But poorly structured, such a tax can curtail domestic production and increase prices. The first step toward taxing oil profits more progressively would be eliminating existing income tax breaks for the industry, which cost about $3.5 billion a year and don’t stimulate production.

Windfall profit taxes proposed last week by Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI) and Rep. Peter De Fazio (D-OR) share certain features, but they differ in important ways and would have starkly different effects.

Whitehouse proposed a per-barrel tax equal to 50 percent of the excess of the current price over the average oil price from 2015 to 2019. Since that price was about $53 and the current price is about $108, the proposal would charge a roughly $27.50 tax per barrel. The tax would apply to the US production and imports of large oil companies that produce at least 300,000 barrels per day.

The Whitehouse WPT does not tax profits, but production and imports. A $27.50 per barrel royalty on the domestic production and imports of major oil companies is equivalent to a roughly $65 per ton carbon tax on their oil.

The Whitehouse WPT would further increase US fuel prices, dampening consumption and reducing air pollution, including carbon emissions. These effects would be muted to the extent that smaller oil companies stepped in to replace production and imports cut back by bigger companies subject to the tax.

By contrast, De Fazio would impose a 50 percent tax on 2022 adjusted taxable income (ATI) that exceeds 110 percent of a company’s average ATI for 2014 to 2019. ATI is income adjusted for net interest expense, dividends, charitable contributions, and net operating losses. The tax would apply only to firms that produce a daily average of 500,000 barrels and have annual gross receipts of more than $1 billion.

Because De Fazio’s proposal applies to oil company profits rather than output, it would be less likely to reduce US oil production and imports or raise fuel prices than the Whitehouse proposal. However, as a temporary profit tax, it imposes some distortions that a well-designed permanent profit tax would not.

Imposing a temporary surtax on profits when oil prices spike creates an asymmetry between the tax treatment of revenue and expenses. Oil companies deduct the cost of their substantial capital investment at the standard 21 percent corporate tax rate, but their income is sometimes taxed at steeply higher rates. This creates an investment disincentive that can lower production.

Both the Whitehouse and De Fazio bills would rebate all revenues back to US households to defray the costs of higher energy prices. The rebates would phase out beginning at $75,000 in income for a single filer ($150,000 for a couple).

Extracting non-renewable natural resources such as oil and gas often generates excess profits, or “rents,” that balloon when prices spike. Taxing these profits is relatively efficient because it doesn’t significantly affect investment and production.

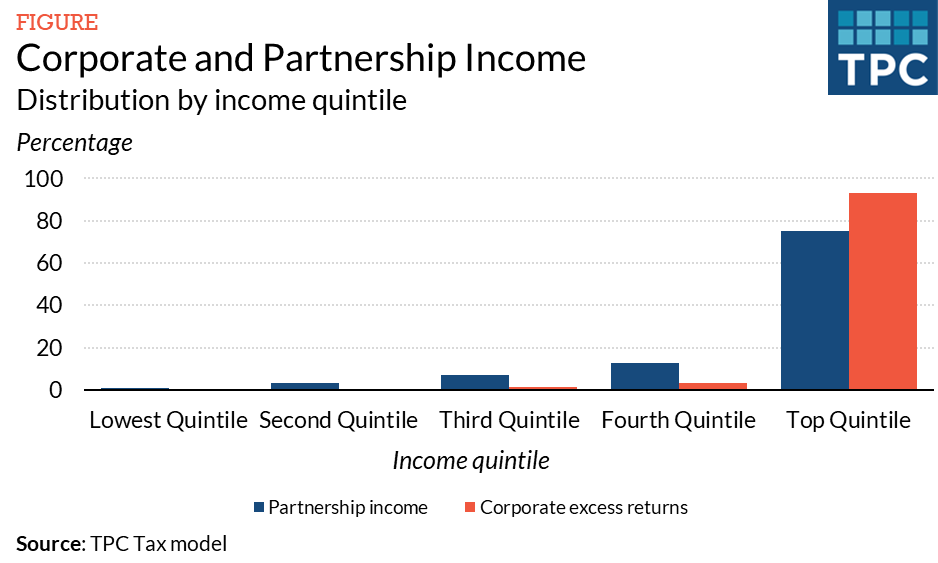

Since petroleum profits accrue largely to upper-income taxpayers, resource rent taxes also are highly progressive. Oil and gas profits are channeled through corporations and partnerships, including publicly traded partnerships. More than 75 percent of partnership income and 90 percent of corporate excess returns accrue to taxpayers in the top income quintile.

For these reasons, many countries including the UK and Norway tax resource rents at higher rates than other business profits, usually with a higher corporate income tax rate or a separate tax on upstream petroleum rents.

There are two major differences between a corporate income tax and a resource rent tax: A corporate income tax allows deduction of interest, while a rent tax disregards financial flows. And a rent tax allows full expensing of capital investment, while a corporate income tax typically requires slower cost recovery.

A profit tax that allows equipment expensing imposes no tax on marginal investment and therefore deters investment very little. The current US corporate tax is a hybrid regime that allows equipment expensing and most interest deductions.

The current tax code also provides $3.5 billion in federal income tax subsidies to fossil fuel producers, which President Biden proposed eliminating in his 2022 budget. Researchers have found these incentives have a minimal effect on domestic investment and output.

Instead of subsidizing petroleum profits, Congress could introduce a permanent petroleum profit surtax to raise revenue in an efficient and progressive manner.