Like all presidential budgets, President Biden’s fiscal year 2024 proposals reflect the priorities he would set for the nation. As in prior years, Biden would raise taxes significantly on corporations and the wealthy, while increasing discretionary spending for a limited period in certain areas.

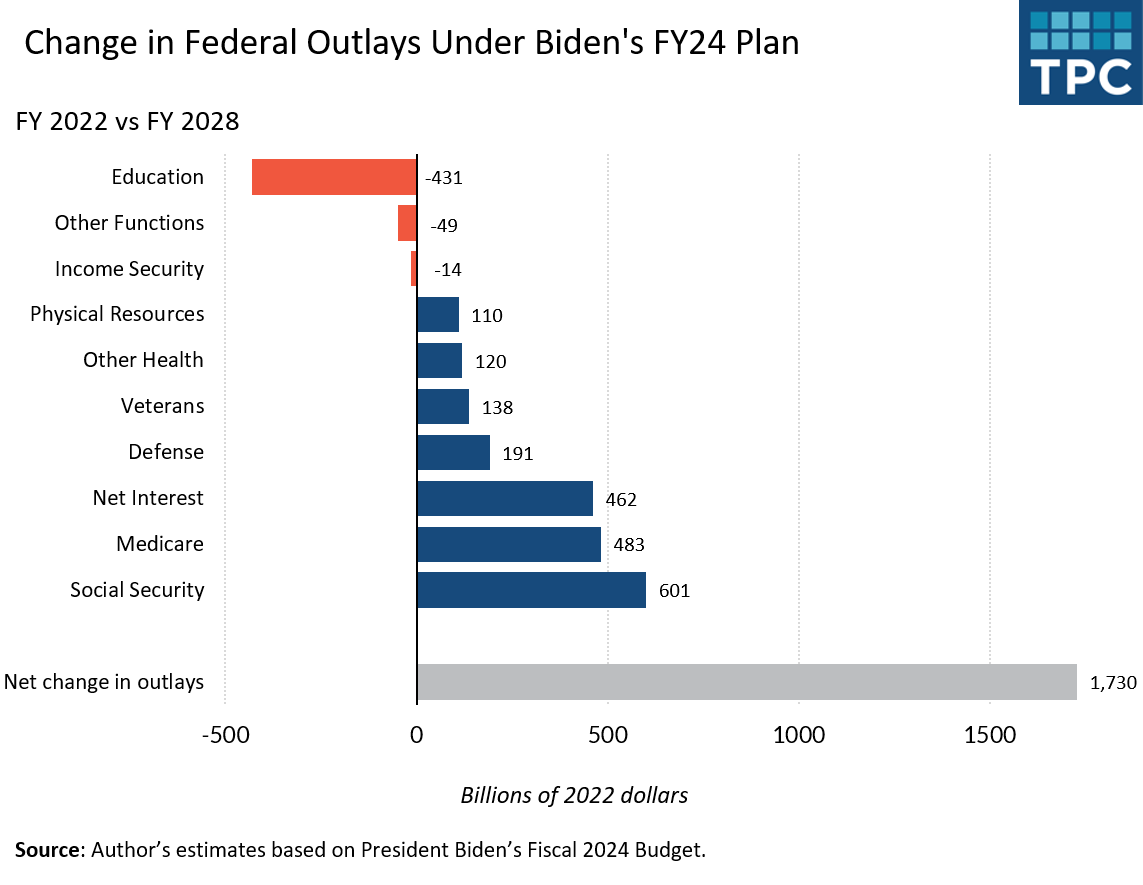

By and large, however, the new budget plan largely reflects an old fiscal path (see figure). By 2028, Social Security, Medicare, and interest on the debt would continue to dominate federal spending, just as they’ve done for decades. Under the laws Biden would enact or sustain, these three items would increase in real, inflation-adjusted dollars by $1.55 trillion. That's about 94 percent of a total increase of $1.65 trillion, as total outlays grow from $6.3 trillion in 2022 to $8 trillion in 2028.

Not shown in the graph, these three major categories of spending would also rise as a share of the nation’s economic output as measured by gross domestic product (GDP). Deficits would continue at an unprecedented rate of between 5 and 6 percent of GDP every year, with no end in sight. Interest on the debt would rise continually to a level of more than 3 percent of GDP, even under the optimistic assumption that interest rates decline over this period.

Of course, modest real growth in major spending categories other than the big three above means that they would grow even slower than the economy. That decline as a share of GDP largely reflects the ending of COVID-era expansions put in place between 2020 and 2022.

The Administration, clearly desires and proposes that some of those past reforms, such as the recent expansion of the child tax credit, continue. But the proposed budget grants Social Security, Medicare and interest on the debt a higher priority status than the child credit, which would only be extended for a couple of years.

The budget’s proposed decline in education spending reflects an accounting currently for the student debt relief the President is attempting through executive action. But it leaves unaddressed issues such as how much students must depend on debt, how higher education subsidies are likely captured by colleges and universities, and who does not go to college or drops out before earning a degree. Policy makers need to take a good, hard, look at what our long-term educational policy should be, both for fiscal sustainability and to support better outcomes.

The point we make is a simple one. Choices have consequences. Giving such high priority to Social Security and Medicare is not just an issue of deficits. It squeezes out other uses of the same money both directly and, over time, indirectly through higher borrowing costs.