The Internal Revenue Service does not ask tax filers about their race and ethnicity. But the US tax code can still widen racial income and wealth inequalities because of long-standing disparities in areas such as housing, education, and employment.

For decades, scholars including Dorothy Brown and Beverly Moran and William Whitford have called attention to these issues. But policymakers have been limited in their ability to diagnose the problem and design maximally effective solutions because of inadequate data.

Now that state of affairs is changing. Responding to President Biden’s Executive Order advancing racial equity, the US Treasury Department has developed a method to impute race and ethnicity to tax data. They recently released details on that method and results of applying it to estimate the effects of special provisions in the tax code that benefit certain sources of income and groups of taxpayers, such as homeowners with mortgage debt.

To add to the understanding of how federal taxes interact with race and ethnicity, the Tax Policy Center, in collaboration with our colleagues in the Urban Institute’s Office of Race and Equity Research, has also enhanced its tax model to enable analysis of the distributional effects of tax policies by race and ethnicity.

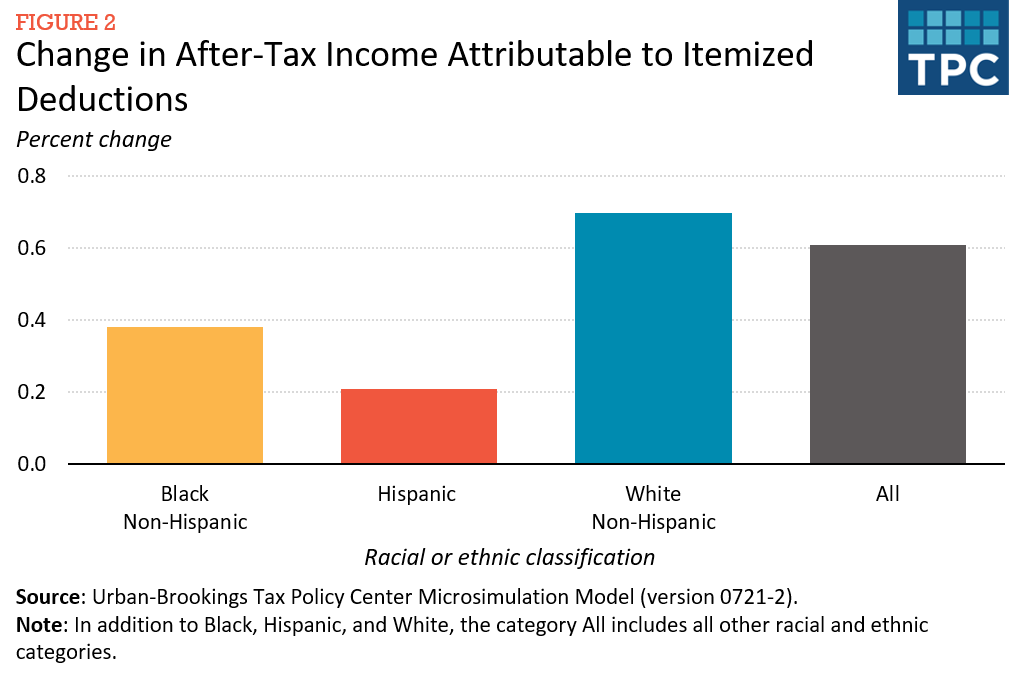

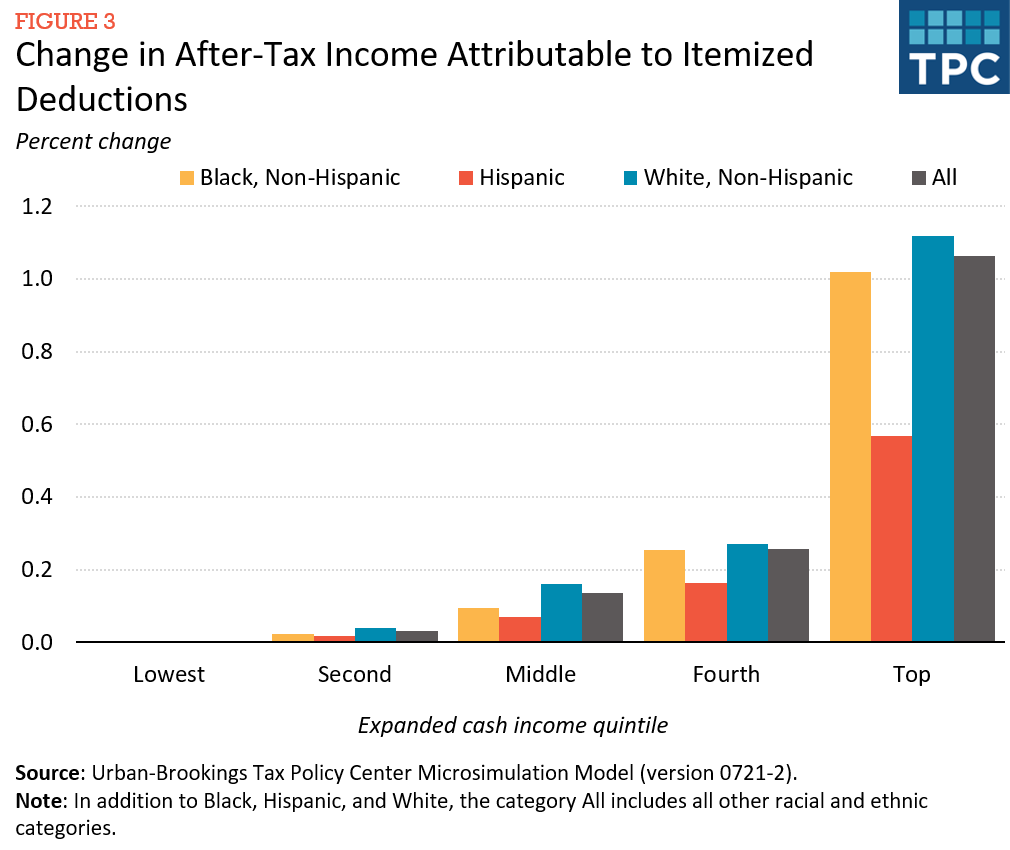

In a new paper, we describe our approach and preliminary results showing that, across all income categories, itemized deductions in total disproportionately benefit White taxpayers over Black and Hispanic taxpayers. And, comparing groups within the same income classes, Hispanic taxpayers benefit less than those who are Black or White.

Measuring the racial equity impacts of the tax system is challenging. The most complete information on tax liability comes from tax return data, which do not include the race or ethnicity of taxpayers. Investigating the racial implications of tax policy therefore requires matching tax data with supplemental surveys or administrative data sources that include information on the race and ethnicity of an individual or a family.

Our approach differs from others being pursued by the federal government and those we know of in other public policy research organizations.

We first replicate each tax unit in the TPC tax model, with one copy for each racial and ethnic category included in the data. Those units are then weighted so that the values for various statistics by race and ethnicity match targets derived from surveys or administrative data (for example, number of dependents, capital gains income, and mortgage interest payments).

Our initial effort relies on two surveys—the Annual Social and Economic Supplement of the Current Population Survey (often called the March CPS), and the Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) – and presents results for calendar year 2019, the most recent year for which SCF data are available.

Our approach offers certain advantages:

- It allows us to incorporate race and ethnicity without having to recreate other aspects of TPC’s model, such as modules for health care, retirement, education, estate taxes, and consumption taxes.

- It incorporates information on relationships between key determinants of tax liabilities and races and ethnicities from more than one source in a straightforward way.

- It enables adding more data and finer grained racial and ethnic categories as this information becomes available.

It also has some disadvantages:

- It relies on the accuracy of the source data used to construct targets.

- It can only produce accurate estimates for tax policies related to taxpayer characteristics for which survey or administrative data are available.

As an initial test of the enhanced model, we produced preliminary estimates of the impact on after-tax incomes of itemized deductions, such as those for charitable contributions, mortgage interest payments on owner-occupied residences, and state and local taxes.

We found that, across all income categories, itemized deductions disproportionately benefit White taxpayers (figure 2). Overall, itemized deductions boost the after-tax incomes of units classified as White by 0.7 percent, whereas those classified as Black gain an average of 0.4 percent, and those classified as Hispanic an average of 0.2 percent. Those differences occur in large part because itemized deductions primarily benefit higher-income households, among whom Black and Hispanic households are underrepresented.

We also found White taxpayers and Black taxpayers benefit relatively more from itemized deductions than Hispanic households, even within the same income categories. For example, among those in the top income quintile (which receives almost 90 percent of the benefits of itemized deductions), itemized deductions raise the after-tax incomes of White taxpayers by an average of 1.1 percent, compared to 1.0 percent for Black taxpayers, and 0.6 percent for Hispanic taxpayers (figure 3).

Understanding the sources of these differences is complex. Future work will examine potential causes ranging from underlying differences in income and wealth to differences in location, access to credit, and family support in addition to the structure of the tax code itself. And we will continue to refine the model, for example by adding other survey information on government benefit programs, consumer purchases, and higher education subsidies. We will also expand our analyses to examine how race and ethnicity interact with other tax exclusions, credits, and deductions and, importantly, what might be the impacts of alternative policies that could help close racial income and wealth gaps.

As we update and refine this approach, TPC will continue to gather input and feedback to ensure we address the most pressing issues and produce the most precise estimates possible. We will also seek other ways to creatively leverage available data to understand this important dimension of tax policy. Ultimately, we hope that providing estimates of the distributional effects of tax policies by race and ethnicity will lead to a more informed debate and promote a more just system for all taxpayers.