When you filed your tax return last spring, did you check off the "Presidential Election Campaign" box on the Form 1040? Didn’t think so.

Hardly anyone did. Indeed, the share of tax filers who check the box to contribute $3 for presidential campaigns has plummeted in recent decades. And because so few candidates in recent years take the money, a portion of the accumulated contributions is being used to fund medical research for children. You probably didn’t know that, especially since the Form 1040 says "Presidential Election Campaign," and not "Presidential Election Campaign/Pediatric Research."

How did we get here? The Presidential Election Campaign Fund (PECF) was established in the 1970s and is subject to the Federal Election Commission (FEC) rules. Congress created the fund in response to concerns about special interests funding election campaigns, including the Watergate scandal, and its goal was to encourage public financing of elections and limit the influence of big donors.

The $3 checkoff is the only source of funds for the PECF. Contrary to popular belief, a contribution does not increase a taxpayer's income tax liability or decrease their refund. It merely directs $3 of tax ($6 for joint filers) to the PECF. The resulting funds are disbursed by the US Treasury to primary and general election campaigns, subject to FEC rules about which campaigns are eligible and for what amounts.

However, the system is failing.

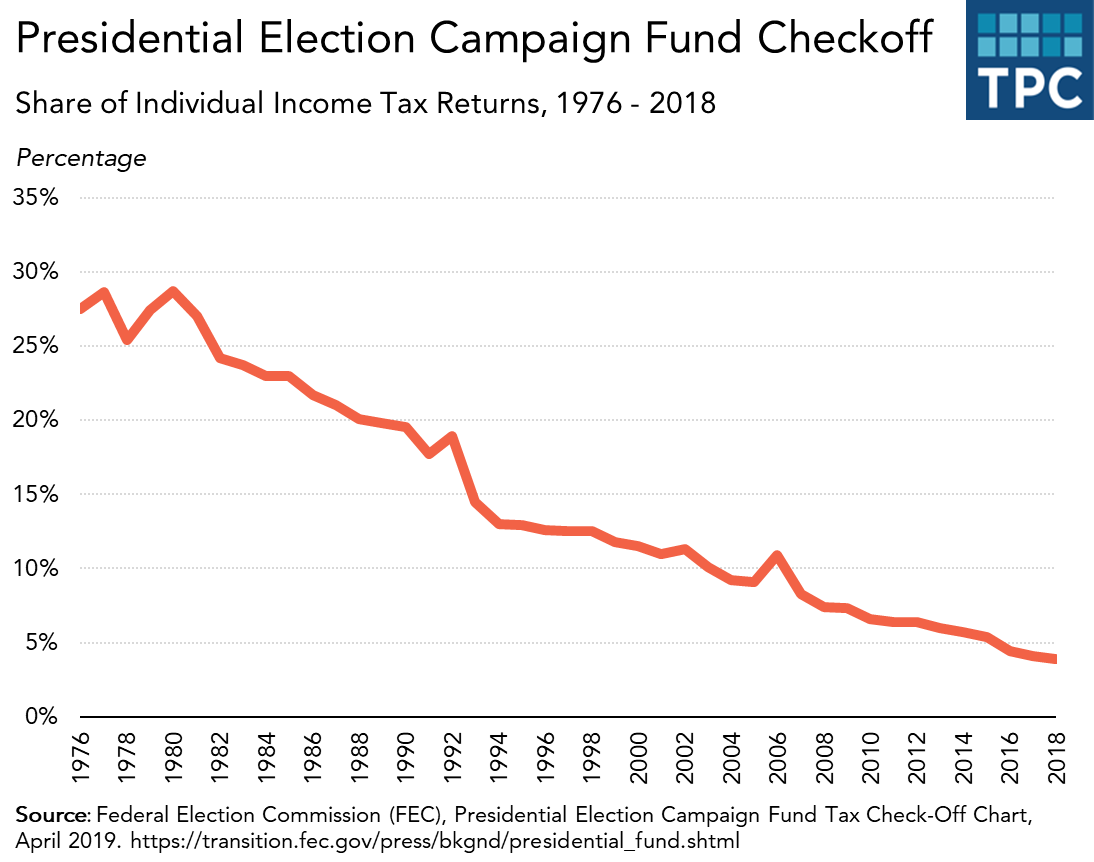

The share of filers who check the box has declined from about 28 percent in 1976 (the first presidential election year for which funds were available) to 4 percent in 2018.

Why are fewer taxpayers willing to support PECF, even if it costs them nothing?

Some may think checking the box will increase their taxes. After all, taxes are complicated, and filers are spending billions of hours and billions of dollars to navigate the complexities. The presidential campaign checkoff is just one more box to fill out.

More likely, it may reflect cynicism about campaign finances or about elections in general (some research shows that public funding of elections can disadvantage incumbent candidates).

We also know that candidates are disinterested in public financing. The last major party nominee to accept public financing was Republican John McCain in 2008. In the 2016 presidential election, only Democrat Martin O'Malley and the Green Party’s Jill Stein took matching primary funds. Neither Hillary Clinton nor Donald Trump made themselves eligible to receive general election funds.

In 2016, the presidential candidates spent a combined $2.4 billion. Facing such expenses, and with the Supreme Court opening the door to effectively unlimited campaign contributions from corporations, unions, and wealthy individuals, no candidate could compete by limiting their campaign spending to the fixed amount of public funds that the PECF provides.

Despite the apparent indifference of both taxpayers and presidential candidates, the $3 checkoff has a unique distinction. It is the only element of the US system of taxation and budgeting that gives the public direct control over how their tax dollars are spent.

The continued use of the checkoff, even if declining, plus a persistent lack of takers has left the PECF with a surplus balance of $392 million. And this has inevitably led lawmakers to look for other uses of the money. For example, in 2014, Congress voted to shift funds that would have been allocated to finance political nominating conventions to pediatric research instead. Just this month, Rep. Mark Green introduced a bill to divert the $3 checkoff to a trust fund dedicated to building a wall on the US border with Mexico.

With the PECF largely ignored by major modern presidential campaigns, it is worth considering whether there are better models. At a cursory glance, it seems like other countries have not had success with public financing of elections for national leaders. Perhaps introducing a state tax benefit for individual campaign donations would be more effective at limiting corporate influence. Alternatively, 2020 presidential candidates like Senator Kirsten Gillibrand and others have suggestions for reforming the federal campaign finance system, while public financing has been more successful at the state and local level.

But in the current political environment, it is hard to imagine that the humble Presidential Election Campaign checkoff has much of a future.