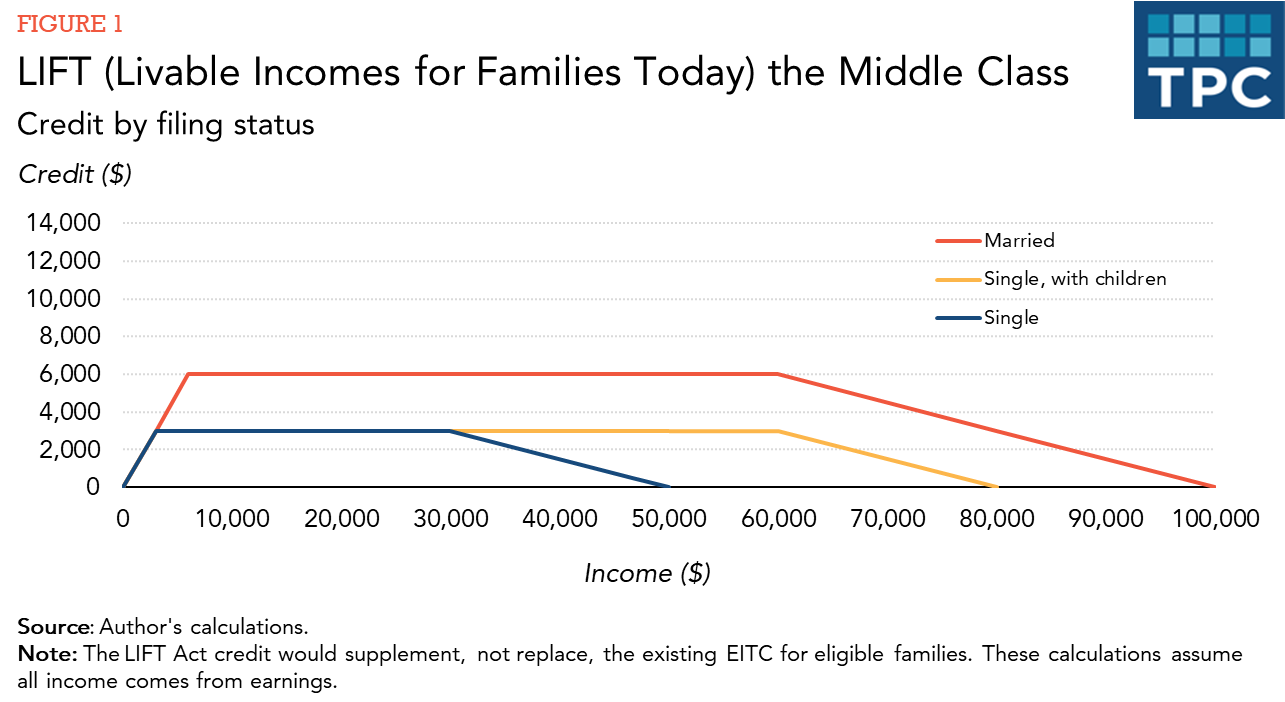

As a senator, Kamala Harris has proposed broad legislation designed to raise the incomes of low- and middle-income workers via her LIFT (Livable Incomes for Families Today) the Middle Class Act. That proposal would provide an annual income tax credit of up to $3,000 for single people and $6,000 for married couples.

While Harris introduced the LIFT Act long before the COVID-19 pandemic, three features make it particularly important under today’s difficult economic situation: (1) The credit would phase in quickly, allowing almost all low-income workers to qualify for the maximum benefit; (2) workers without children at home would be eligible for the same maximum benefit as workers with children at home; and (3) the credit could be paid on a monthly basis.

Tax Policy Center estimates this proposed tax credit would deliver about $2.7 trillion in benefits over the 10-year budget window, one of several recent proposals to expand work or child credits. The new LIFT tax credit would be on top of the existing earned income tax credit (EITC)—it would not replace the EITC.

The proposed LIFT Act tax credit is similar to the earned income tax credit: Benefits phase in with earnings, reach a maximum, and then phase out. Benefits for the LIFT Act phase in at a rate of 100 percent—for each dollar of earnings, workers qualify for a dollar of tax credit. This relatively steep phase-in means that almost all low-income workers would receive the maximum credit, even if they work part-time or part-year. That’s particularly important when so many people have lost (or are losing) jobs, thus working less than a full year in 2020, or when workers see their hours cut.

The LIFT Act tax credit also largely separates the amount of benefits from whether or not the taxpayer has children: Single people qualify for up to $3,000 in benefits, married couples qualify for up to $6,000 in benefits. As a result, the LIFT Act tax credit would provide 44 percent of its total benefits to workers with children at home—a much more even share than the EITC which delivers roughly 97 percent of its benefits to families with children. Combined, the EITC and the LIFT Act tax credit would provide about half of total benefits to workers without children at home and half to workers with children at home.

Separating children from benefit level not only allows workers without children at home to receive substantial benefits; it also would make administering the LIFT Act tax credit simpler than the EITC. In most cases, the IRS would not need to determine which household children lived in, something that has historically been difficult for taxpayers to comply with and which gives rise to many EITC errors.

Finally, the LIFT Act tax credit could provide ongoing support to workers who claimed the credit on a monthly, rather than annual basis. This could help many low-income people meet ongoing needs and avoid costly short-term borrowing.

On the downside, like all credits that phase out, the proposed tax credit would increase marginal tax rates on workers with income in the phase-out range, which could discourage some from working. However, research suggests that effect on labor market participation is likely to be small and apply mostly to secondary earners in married couples.

Senator Harris’s LIFT Act was among the larger of the new tax credits to support work and families that lawmakers have proposed recently. Whether it will become part of Biden’s own tax plan is unclear – but it does demonstrate Harris’s longstanding commitment to increasing the incomes of low- and middle-income workers.