Coal miners increasingly are victims of a cruel paradox. Even as production declines, more are suffering from deadly black lung disease. Yet falling production and growing efforts to combat climate change will slash the federal funds to support sick workers and their families.

This problem can be resolved, but it will require policymakers to rethink both the tax that funds the federal black lung trust fund and the structure of the program itself.

Since its peak in 2008, US coal production has fallen by over half. But the industry continues to leave a scarring legacy on the land and in the lungs of miners. More than ten percent of coal miners with 25 or more years’ experience in underground mines have coal workers’ pneumoconiosis, or black lung disease. Mysteriously, even as coal production has declined, coal miners in central Appalachia have suffered an unprecedented surge in the ailment; as many as one in five have the telltale shadowy chest x-rays.

By law, coal mine operators must provide disability benefits to injured workers. But when there’s no money left—often as a result of bankruptcies designed precisely to shirk those responsibilities—the federal government takes over. Between 2014 and 2016, for example, the federal Black Lung Disability Trust Fund assumed more than $865 million in liabilities as a result of coal operator bankruptcies.

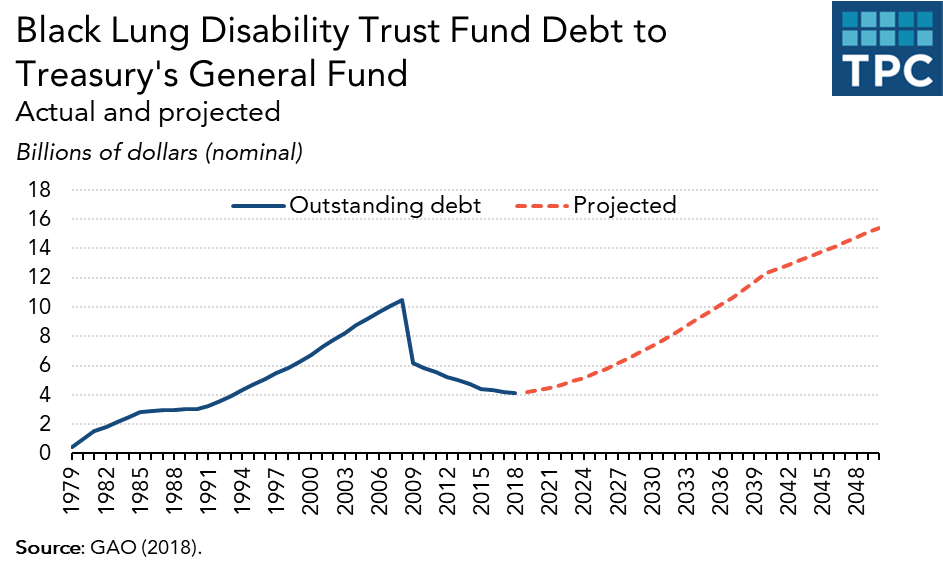

The trust fund primarily gets its revenue from a small excise tax on US coal production. While in principle this revenue source makes sense, the fund has run a deficit since it was created in the 1970s. Even after Congress forgave $6.5 billion in debt in 2008, compounding interest on the remaining debt is add adding billions of dollars more to its underfunded liabilities.

Rising numbers of potential beneficiaries and the eroding economics of the US coal industry make the fund’s fiscal outlook even bleaker than the General Accountability Office’s projections from 2018, shown above. In addition, recent research from the Brookings Institution projects that if the coal excise tax rate drops as scheduled next year and policymakers implement any climate program equivalent to a modest tax on carbon dioxide, black lung excise tax collections will collapse.

Although Congress has authorized the trust fund to borrow from the Treasury’s general fund indefinitely, black lung benefits remain vulnerable to the vagaries of federal budget politics.

Reforming the system could ease the lives of disabled miners, make the program solvent, and distribute burdens fairly. One priority should be to fund research to measure and explain the recent surge in black lung disease. Some experts hypothesize the condition is increasing due to silicosis from the rock dust prevalent in underground mines with thinning coal seams.

The Department of Labor also needs to significantly improve its oversight to be sure coal mine operators adequately prepare for their black lung liabilities. Congress also could reform the protracted and financially-conflicted system miners face in accessing benefits. Recent evidence shows that the likelihood of physicians finding coal workplace illness disturbingly depends on who’s paying them.

To resolve the decrepit fiscal condition of the black lung program, policymakers could allow the Treasury to adjust the coal tax rate periodically to cover current and projected federal black lung expenses and gradually retire the trust fund’s debt. This would adapt the program to fluctuating coal production levels and beneficiary numbers and keep the responsibility on coal companies. Further, mine operators would know that if they declare bankruptcy at one facility, the tax rate on their coal produced elsewhere will rise, reducing their incentive to restructure.

Soon, however, US coal production may fall to levels insufficient to fund black lung benefits appropriately. As the coal industry’s dust settles, an obvious option is a fee on the carbon content of all climate-damaging fossil fuels. If imposed economy-wide, a small fraction of a single year’s proceeds could fund robust benefits for coal miners and their families and retire the trust fund debt. It could also help coal-reliant areas cope with other costly legacies of the industry, such as abandoned mines and hollowed out revenue systems.

With smart new policies, Congress could address rising black lung disease even as coal production declines.