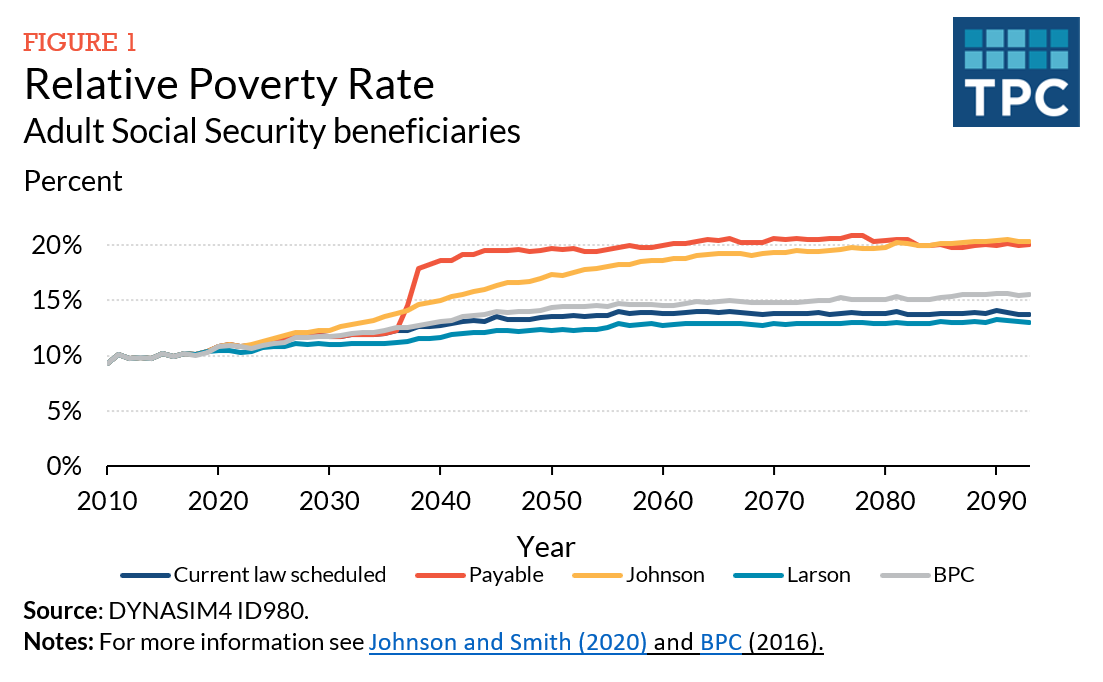

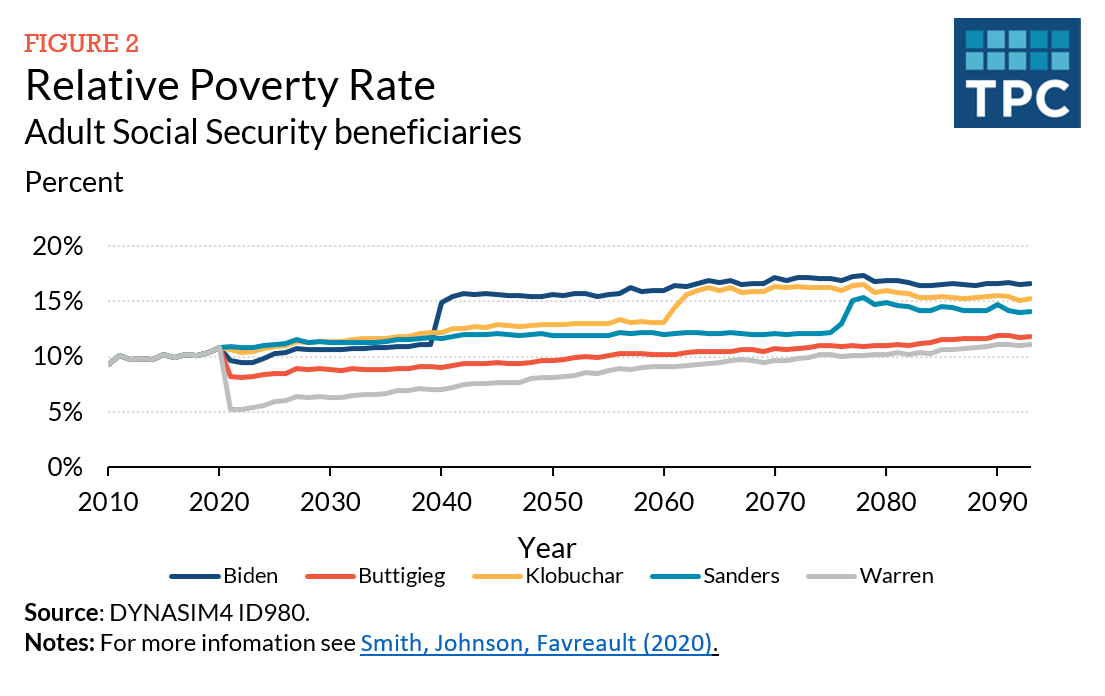

Most Social Security reform proposals have focused on one goal: restoring the program’s long-run fiscal balance. Yet under all recent proposed restructurings we have examined—whether by Democrats or Republicans in Congress, in the presidential campaign, or by a bipartisan commission—the share of older adults and younger people with disabilities who live in relative poverty would rise in the future (see figures 1 and 2).

This is upside down: given the substantial increase in benefits scheduled for future retirees under every one of these reforms, policymakers should first seize the opportunity to look at how Social Security reforms can alleviate poverty and, next, how to provide adequate protections for moderate income workers. Then, they can fight over whether to make the system solvent by raising taxes or slowing the growth in promised benefits for everyone else.

In a recent paper, we examined how a basic minimum benefit could essentially eliminate poverty among older adults and people with disabilities. We assessed various effects of a minimum or floor benefit for almost all elderly and disabled individuals equal to the poverty level for a single individual, which equates to a bit less than 25 percent of the average wage in the economy. We also indexed it so, like other Social Security benefits, it would grow at the same rate as average wages.

To show how such a reform might work, we added it to three prominent Social Security proposals that sought long-term solvency—Representative John Larson’s (D-CT) that achieves solvency almost entirely through tax increases; former representative Sam Johnson’s (R-TX) that depends almost entirely on reducing the rate of benefit growth; and the Bipartisan Policy Center’s that proposes a mix of tax increases and benefit cuts—all of which, like current law, would allow relative poverty to rise.

We find that the additional cost of a minimum benefit is sufficiently moderate that any of these proposals could reduce poverty, be solvent, and still provide significantly higher real benefits across the board for future generations.

When President Franklin Roosevelt signed the Social Security Act in 1935, he was explicit about his goal: "We tried to frame a law that will give some measure of protection to the average citizen...against poverty-ridden old age."

Social Security also attempts to pursue individual equity by partially imitating private retirement plans, where a worker’s accrued benefits rise with accrued contributions. Social Security does this mainly by providing those with higher earnings a higher benefit on average.

But the current system achieves neither progressivity nor individual equity very effectively. Some benefits are unrelated to either contributions or need. For example, the survivors and spouses who benefit most from current spousal rules are nonworkers who contribute nothing themselves but marry very high earners. Their working spouses also contribute nothing for this extra protection, either directly or indirectly through an adjustment in their own benefits, as they would with a private annuity.

By contrast, a minimum benefit targets need far more effectively, rather than subsidizing individuals based on some characteristic that only loosely correlates with need. It achieves a degree of progressivity, as well as gender and racial equity, that many believe Social Security provides but does not.

Social Security currently provides a special minimum benefit, but the indexing provisions of this benefit have reduced its value to almost zero for all new retirees, leaving many individuals with low lifetime earnings with benefits below poverty.

Our study examines a minimum benefit both to Social Security beneficiaries and to Supplemental Security Income (SSI) recipients who do not qualify for Social Security because they have made less than ten years of contributions to Social Security. It leaves open whether the SSI extension should be financed through general revenues or Social Security trust funds. It warns, however, that past jurisdictional line-drawing between Social Security and SSI has led to neglect of many of the neediest elderly and disabled individuals, as many reform efforts throw up their hands and imply that that problem is someone else’s to solve.

Congress will soon have to address Social Security’s coming insolvency to ensure that existing retirees can maintain their current benefits. Major Social Security reform, which sets standards for decades to come, is an ideal time to address poverty among older adults and younger people with disabilities.

Although lifetime Social Security and Medicare benefits are scheduled to increase unsustainably from about $1 million for a typical Baby Boom couple to $2 million for a typical millennial couple, economic growth still provides the ability to increase benefits substantially for future retirees under almost any reform. As a result, Congress could eliminate poverty among Social Security recipients while still allowing future retirees at all income levels to receive hundreds of thousands of dollars more in lifetime benefits than today’s retirees.

Social Security reform won’t be easy, but it can’t be dodged much longer. Policymakers who soon must decide how to allocate trillions of dollars in higher future benefits have a unique opportunity at last to eliminate poverty for the elderly and for recipients of disability benefits.