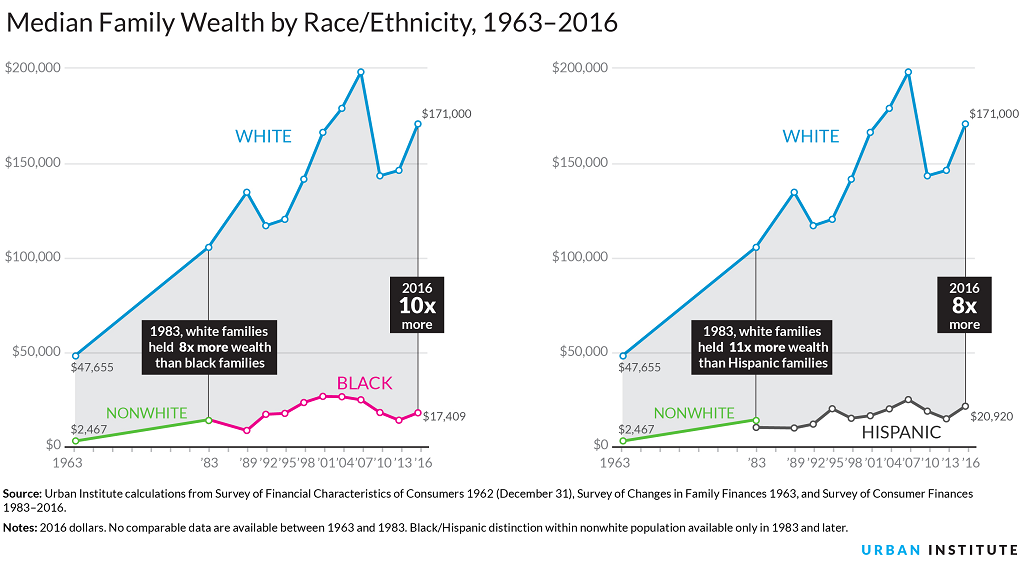

Every Democratic candidate for president has a plan to address growing inequality in America (on January 16, the Tax Policy Center sponsored a program on inequality viewable here). Yet few presidential candidates wade into what is arguably the most intractable dimension of inequality – the racial wealth gap (shown in the figure below to be increasing over time). Logically, these candidates’ solutions focus on the role of federal level policy. However, reducing overall inequality must recognize that the nature of wealth differs by geography. Thus, state and local governments have a role to play, and arguably have different tools than the federal government to address the racial wealth gap.

In a 2013 paper, researchers tracked wealth accumulation over a 25-year period, and they found that the major drivers of the wealth gap were: home ownership (27% of the gap), wage inequality and unemployment (combined for 29%), college education (5%) and inheritance (5%). In each of these areas, state and local governments have actionable tax policy tools at their disposal.

Home equity. An important step to lessening wealth inequality across racial groups is to increase home ownership by people of color, an area in which federal policy can and does play a significant role. However, even if the rates of home ownership are equalized, the home value appreciation gap would still impair the wealth creation for households of color. And local governments can play a role in closing that gap.

These governments can significantly impact the wealth accumulation of home owners through the investments they make in black and brown communities through outlays of resources and through tax expenditures. And although a significant gap in home values remains even when similar amenities are available, investments can decrease that gap within a metro area. And more importantly, the absence of these investments (such as transportation and community spaces) all but ensures that these communities will remain in a state of comparative disadvantage. Judicious use of tax incentives can increase economic activity by as much as 20 percent within metropolitan areas. In Franklin County, Ohio for example, targeted tax incentives served to boost growth, increase property values, and decrease property taxes for historically disadvantaged Community Reinvestment Areas and Enterprise Zones .

Wage inequality. Deindustrialization, manufacturing decline, and historical discrimination in labor markets all have had a disproportionately negative impact on the financial stability and wealth-accruing potential of black and brown communities. And recent research by the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland argues that the racial income gap is an even larger contributor to the racial wealth gap than previously known.

State and local tax policy is one of the many factors that can drive the growth of high-wage jobs with wealth-building potential. While the use of tax expenditures for economic development and job growth is common among virtually all states, they are not typically designed to effectively deliver on the promise of quality jobs to the communities that need them most.

However, cities like Austin TX are improving access to quality jobs for disadvantaged citizens by

incentivizing companies (though tax breaks) to provide employment pathways to children out of poverty into jobs that pay an average of $100,000. This approach reflects a commitment to a model of economic development that restructures tax incentives to address community goals like reversing historically rooted disinvestment patterns.

College Education: Lower family wealth means that minorities are more likely to rely on debt to finance higher education, and greater debt exacerbates the racial wealth gap. Minority students have higher student loan debt, higher interest rates, and higher loan default rates. Federal and state expenditures go hand in hand to address the three phases of postsecondary education financing (savings, lowering expenses, and debt). For instance, increased public support for higher education can reduce the cost of attendance.

State tax policy can play a role, too. For example, thirty-four states offer tax credits or deductions for higher-education savings plan contributions. For most states, the value of these benefits to families is minimal. Indiana’s credit is one of the largest, and it provides a maximum benefit of $1,000 per taxpayer per year. Some states also allow taxpayers to deduct student loan interest or tuition and fees in computing taxable income. But deductions often don’t benefit low-income families. Refundable tax credits like South Carolina’s $1500 credit, for tuition and fees paid, have a greater potential to benefit lower- and middle-income families.

Inheritance. There is a robust conversation occurring nationally concerning federal wealth taxes and the racial wealth gap. But at the state and local level this conversation is limited to just a few locations. Even the 17 states with inheritance taxes do not have demonstrably lower racial wealth gaps. Some would argue that this evidence supports the claim that wealth taxes aren’t a good tool for addressing inequality. But the seeming ineffectiveness could also be a function of the flawed design of the taxes, the depth of the challenge, and what some deem as a failure to target state revenues towards strategies aimed specifically and directly at addressing historically rooted and institutionally reinforced structural inequities (e.g. human capital and infrastructure).

These structural factors can impede wealth accumulation, and these factors are reinforced by policy decisions at various levels of government. But directly addressing these inequities does not have to be a zero-sum game. Research suggest that reducing the wealth gap could increase US GDP by 6 percent by 2028. In every state and locality, what’s needed is an evidence-based conversation around these areas and a willingness by communities to embrace policy innovations and dispel fears like residential flight and the fear of losing out on the next firm location decision to neighboring communities. Reducing racial wealth inequality won’t be easy, but in these ways, we can begin to make some progress.