As the first day of school approaches, remember that the quality of a child’s education is largely determined by where their public school is located. And in many cases, the roots of educational inequities lie within state and local tax policy.

While school districts get revenues from multiple sources, state and local money is most important. Each state has its own complex web of rules and formulas that determine this funding. But nowhere is it more complex than in my home state of Colorado. Tax limits and workarounds to them have especially hurt school districts that serve rural and high-poverty areas and pushed some to adopt a four-day school week.

Tax limits constrain education funding

The fiscal equation is especially complex in Colorado because of tax limitations and mandates on how state funds are distributed. The 1992 Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights (TABOR) requires voter approval for tax hikes and caps annual tax revenue growth. Many states have some type of tax limit, but TABOR is one of the most restrictive in the country.

Another Colorado tax restriction, called the Gallagher Amendment, limited the ability of school districts to raise property taxes. Until its repeal in 2020, it fixed the relationship between the assessed value of residential and commercial property. As residential property values rose faster than commercial property values, the Gallagher Amendment forced the state to lower the residential assessment rate.

In 2000, partially in response to declines in public school funding that resulted from tax limits, Colorado voters passed Amendment 23 that required the state to increase education spending every year. However, during the Great Recession, a revenue shortfall prevented state lawmakers from achieving that goal, and ever since, they have used a tool called the “Budget Stabilization Factor” to cut state aid to all school districts below the amount deemed necessary by the state funding formula. The result: Districts have to use local property taxes to make up the difference.

Colorado voters can override local property tax limits. However, it has not been easy to win voter approval for tax hikes, especially in communities with larger funding disparities. For example, voters in the rural Trinidad School District No. 1, where over 29 percent of children are estimated to be living in poverty, rejected a proposed property tax override in 2016 while Denver voters approved an increase that raised an additional $798 per student.

Tax limit workarounds can have disparate effects

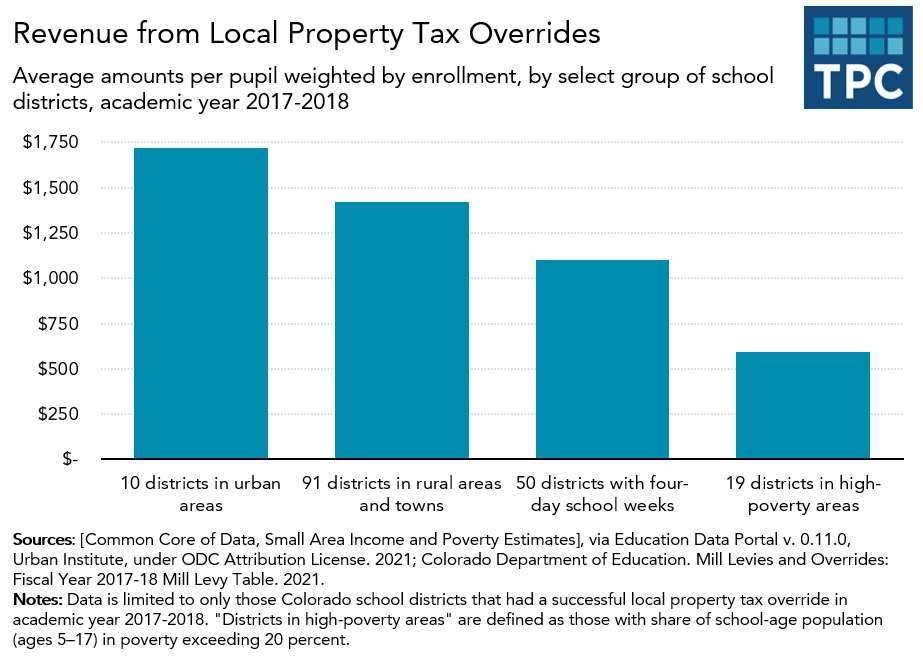

The Urban Institute and the Colorado Department of Education found that in academic year 2017-2018, one-in-three Colorado school districts did not raise any revenue from voter-approved overrides to local property tax limits.

Since the funds from a property tax override may not be used for capital construction or renovation, the money often is earmarked to promote equity. For example, in 2018, Jefferson County voters approved a $33 million tax hike to expand early childhood education and improve career and technical training. The absence of property tax overrides may slow progress toward educational equity.

Overall, 15 percent of Colorado’s K-12 students attend school districts in rural areas, and 7 percent live in high-poverty school districts. But among students attending school districts where voters did not approve property tax increases, 43 percent live in rural areas and 41 percent in high-poverty areas.

Even with the same property tax rates, districts serving rural or high-poverty areas often are unable to raise as much revenue as urban or wealthier communities. For example, levying one additional mill (0.1 percent) during the 2017-2018 academic year raised $190 per student in Denver Public Schools but just $19 per student in rural Fountain-Fort Carson.

Colorado is not alone. For example, Measure 5 in Oregon limited local property taxes while increasing reliance on more erratic state aid from income taxes. Similarly, Proposition 13 in California shifted the burden of school funding toward the state, but most school districts saw per-pupil revenue decline over time. Yet previous research shows that school funding can be a crucial determinant of student achievement outcomes. Coloradans started addressing this disparity when voters abolished the Gallagher Amendment and lawmakers agreed to reevaluate the state’s 25-year-old school funding formula. These changes could help school districts maintain their property tax bases and redirect larger shares of state aid to where it is most needed.

As many children return to the classroom for the first time in over a year, policymakers in Colorado and beyond should reexamine their complex webs of tax rules. They should restructure their education funding models to achieve the goals of adequate and equitable school funding.