In fiscal year 2020, Georgia will spend nearly $500 million in film and television tax credits in return for the promise of new jobs and economic growth. The familiar “Georgia peach” that you may have noticed in the closing credits of a feature film is just one small example of how states use tax expenditures, or forgone tax revenues, to benefit specific activities or taxpayers. Called tax expenditures because many serve the same function as direct spending while being delivered through the tax system, these subsidies are a significant source of fiscal intervention for both the federal government and states. But they are often overlooked because they are administered through a state’s tax code.

In a new research brief, we use three states—California, Massachusetts, and Minnesota—and the District of Columbia (that we treat as a state) to show how tax expenditures work at the state level.

Among these four states, individual and business tax expenditures range in size from 51 percent of total income tax revenues in California to 61 percent in Minnesota in fiscal year 2020. Roughly three-quarters of the lost revenue comes from federal income tax provisions that are retained by most states that conform their tax codes to federal tax law. However, states also subsidize activities through their own tax expenditure provisions.

Conformity and Federal Linkages

State tax codes are connected to federal law because many start their tax calculations with the same measure of income as reported on federal tax returns. California, the District of Columbia, and Minnesota use federal adjusted gross income as their income base and thus automatically incorporate all major federal exclusions, exemptions, and adjustments to income. Massachusetts starts with gross income instead, but allows some of the same adjustments as the federal income tax.

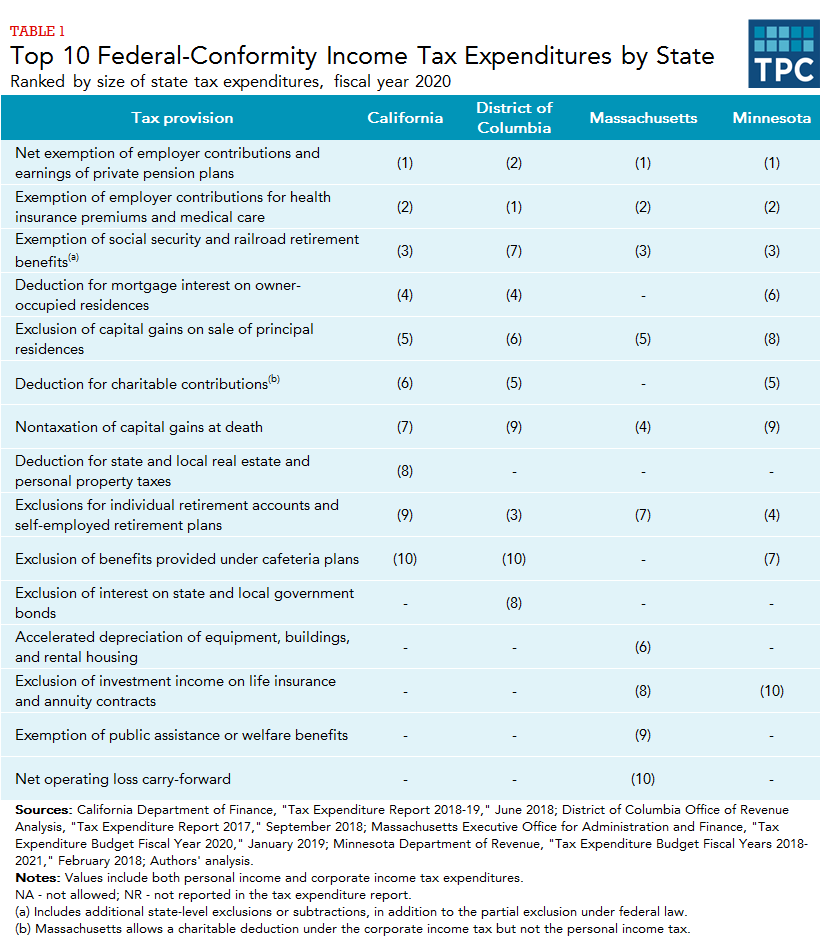

As a result, the largest state tax expenditures closely resemble major federal preferences. For example, exclusions for employer contributions to employee retirement and health insurance plans are the two largest in each of our four sample states. Overall, we find that federal tax provisions followed by state law constitute 70 percent to 85 percent of the total cost of combined individual and business income tax expenditures in these states.

State-Specific Provisions

States also have considerable latitude to implement their own tax expenditures to encourage certain taxpayer behavior. These include provisions that subsidize business costs for certain industries and that promote other public goals, such as income support, healthcare, or housing.

These often include state versions of the federal earned income tax credit (EITC), or similar tax credits for low-income working families. EITCs are the largest state-specific tax expenditure in the District of Columbia (costing an estimated $79 million in FY 2020) and Minnesota ($270 million), and the fourth largest in California ($370 million) and Massachusetts ($280 million).

Economic development subsidies such as Georgia’s film tax credits are also common, but the type of incentives and target industries can vary widely. For example, tax credits for qualified business research costs an estimated $1.7 billion in California, $284 million in Massachusetts, and $77 million in Minnesota. Massachusetts also offers further tax incentives for the life sciences industry, costing about $18 million. By contrast, the District of Columbia does not have research credits, but offers $33 million for a suite of tax preferences that benefit qualified high-technology businesses.

Reporting and Monitoring

Reporting of tax expenditures also varies because each state has its own tax system, with its own set of federal conformity rules and definitions of what counts as a “special” provision. For example, California considers head-of-household and qualifying widow filing status as tax expenditures because they offer lower tax rates than rates for single filers with the same incomes. But other states consider tax rate schedules by filing status an integral part of the basic income tax base structure.

This discretion, along with spotty accountability metrics, can make monitoring of state tax expenditures particularly challenging.

But there have been improvements in recent years. Some states are giving extra scrutiny to economic development programs such as film tax credits or other tax incentives intended to attract and retain businesses. And, in addition to reporting on costs, states like Colorado and Rhode Island are adding more rigorous audits to determine how well these incentives influence business behavior, their economic trade-offs and indirect effects, and whether their objectives match their outcomes.

State tax expenditures can be costly, but may also benefit important societal goals such as economic development, affordable housing, and income security. If ill-considered or poorly designed, however, they can provide unwarranted special benefits to certain industries or individuals. Therefore, states should report on both their federally-derived and own tax expenditures regularly and carefully evaluate each provision.

Tax expenditures are an important fiscal tool for state governments. They deserve more attention, and our new research brief is an effort to increase transparency.