Thanks to surging tax revenues and an unprecedented infusion of federal aid, many states cut taxes over the past two years by lowering individual income tax rates, expanding tax credits, or sending one-time checks to residents. But there is another way states can use these funds: help local governments reduce or eliminate some criminal legal fines and fees.

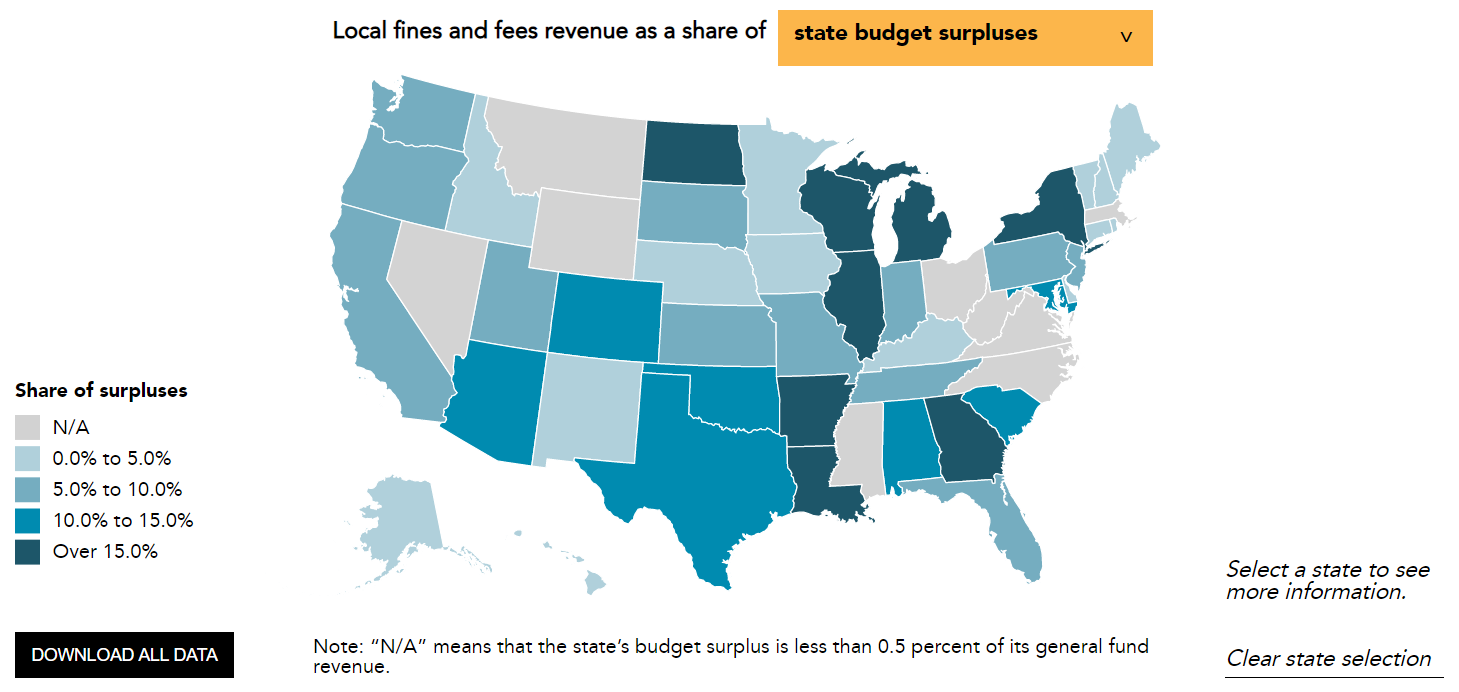

The Tax Policy Center has developed a new interactive data feature that shows what it would cost for states to use their surpluses to replace revenues collected through criminal legal processes.

Fines and fees make up a small share of state and local revenue overall, but can be devastating for low-income residents, especially Black, Latine, and Native American households, who are disproportionately affected by criminal legal systems. These penalties, such as traffic tickets and court costs, also create harmful incentives for police departments and courts to pursue revenue generation, which can undermine trust and negatively impact public safety.

In 2019, state and local governments raised $14.8 billion from fines and fees, less than 0.5 percent of their combined general revenues. States raised $5.6 billion, and localities raised $9.2 billion. Of course, states flush with budget surpluses and federal fiscal recovery funds could use their resources to reform their own fines and fees. But cities and towns tend to rely more on these revenues than states, and, critically, many local governments have few other revenue options, making reforms challenging.

Our research shows what it would cost for states and localities to wipe away all local fines and fees for just one year and backfill that lost revenue with state funds. Such reforms could take a heavy burden off some residents and give local policymakers and administrators resources and time to explore more equitable and reliable revenue sources.

We recognize that few jurisdictions will eliminate their entire slate of criminal legal penalties. But aggregate data help us understand the magnitude of the state-by-state costs needed to suspend local fines and fees. In practice, policymakers would face lower costs if they target specific fines or fees they deem worth eliminating.

For example, we show it would take less than 1 percent of all states’ combined 2022 general fund revenue to help localities wipe out fines and fees and replace them with state funds for one year. For 20 states, including Connecticut, Hawaii, and Kentucky, it would require just 0.5 percent of their respective general fund revenues.

Similarly, it would take less than 5 percent of fiscal year 2022 budget surpluses to replace local revenue from fines and fees in 14 states, or a similar share of unallocated Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds in eight states.

Local fines and fees do not generate a large share of local revenue overall, but some places come to rely on them. Georgia, Louisiana, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Texas each have more than 50 local governments that collect more than 10 percent of their general revenue from fines and fees. And in each of those states, a handful of small towns rely on fines and fees for over half their budgets. One recent example: Brookside, Alabama.

Further, not all fines and fees assessed are collected. The amount of uncollected court debt across the nation totals tens of billions of dollars. Those with an outstanding bill can face late fees and interest, license suspensions, loss of voting rights, and incarceration. And, some local governments spend more to enforce collections than they raise.

Some states already are taking steps to reform their criminal legal systems. California’s Families over Fees Act and subsequent legislation permanently repealed 40 administrative fees, backfilled $65 million in lost local revenues, and discharged about $16 billion in debts that were considered largely uncollectible. Colorado, Louisiana, Texas, and other states have scrapped many juvenile fines and fees.

Our new interactive data feature can help state and local leaders begin to understand what it would cost to repeal fines and fees. After two years of state revenue growth, these targeted and equitable reforms could improve fiscal management and help ease financial burdens on those struggling the most.