All states with an income tax link to the federal tax system to some degree. This system of federal-state conformity helps taxpayers by standardizing the rules of our various income tax systems and helps states by simplifying tax administration and compliance. Yet there is a downside: conformity can put state income tax revenues at the mercy of federal policies.

The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) is a good example. A year and a half after the law’s passage, states still are dealing with the way the TCJA automatically changed their tax systems.

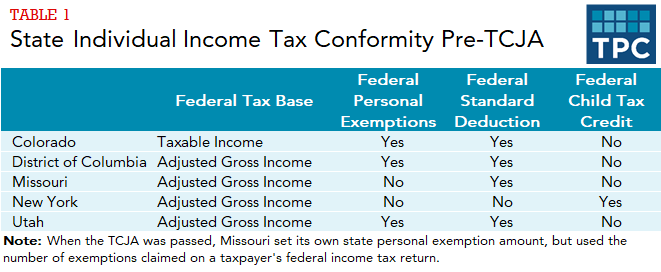

To measure how these changes might have affected the states, my colleagues at the State and Local Finance Initiative and I explored how state income tax revenue would have changed if all the automatic changes prompted by the TCJA flowed through to state tax systems unaddressed. We chose five jurisdictions that link to the federal tax code differently: Colorado, the District of Columbia, Missouri, New York, and Utah (table 1).

Of course, many states changed their rules in response to the TCJA, but it is instructive to look at how the law would have affected state income taxes if states had not adapted. At a minimum, our analysis illustrates the scale of the impact.

What we did

We modeled four TCJA individual income tax provisions that are particularly important to state income tax systems:

- The increase in the federal standard deduction

- The elimination of the federal personal exemption

- The expansion of the child tax credit (CTC)

- Changes to federal itemized deductions

What we found

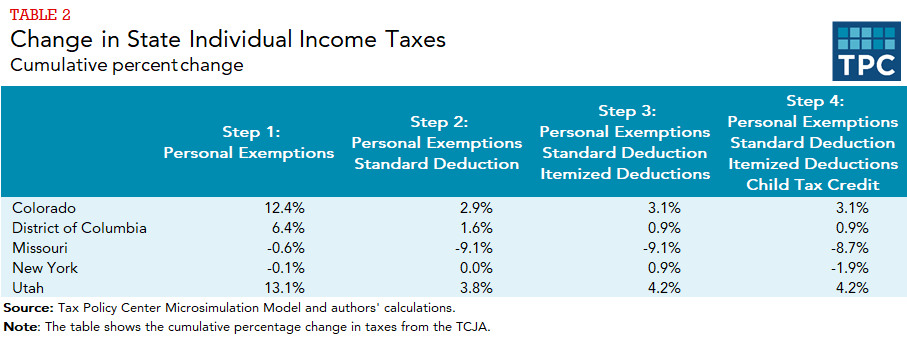

At the federal level, the increase in the standard deduction roughly offsets the elimination of personal exemptions for taxpayers (though not for their dependents), and states that conform to both the standard deduction and the personal exemption experience a similar offset. This is evident in Colorado, the District of Columbia, and Utah, which conform to both provisions and do not offer a federally-linked child tax credit. The effect of eliminating personal and dependent exemptions, so we estimated that taxpayers in these three jurisdictions would have paid slightly more post-TCJA (table 2).

By contrast, we estimated New Yorkers would have paid slightly less in state income taxes. New York is one of the few states with its own child tax credit. And, because it is based on the size of the federal child tax credit, the New York credit would have increased automatically as a result of the TCJA. We estimated that the state’s revenue loss from the expanded child tax credit would exceed the tax increase from changes to the federal schedule of itemized deductions, cutting net state income taxes by 1.9 percent.

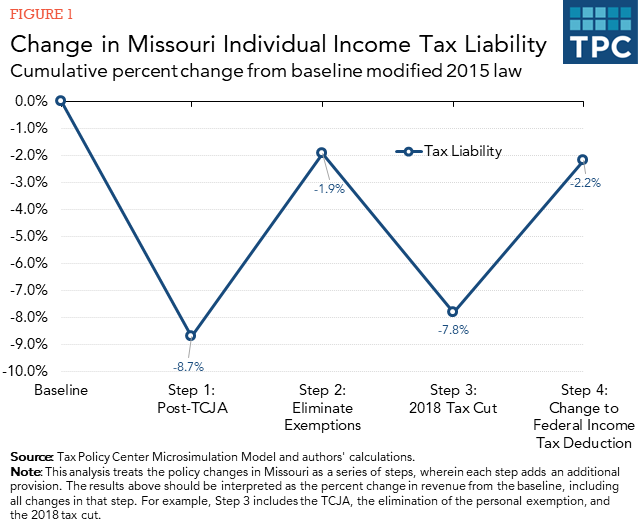

We saw the largest potential effect in Missouri, which we believed to be in the unique position of conforming to the newly-doubled federal standard deduction but not to the newly-eliminated federal personal exemption. Conforming to one provision but not the other means losing the offsetting effect present at the federal level and in the other states we modeled. We estimated that if Missouri were to roughly double its standard deductions while keeping personal exemptions at the pre-TCJA level, taxpayers would have received an average income tax cut of nearly nine percent. Of course, that would have resulted in a significant drop in to state income tax revenues.

How states have responded

Now, a year and a half after the passage of the TCJA, we can see how states responded to the pressures created by the federal law change.

Missouri interpreted the federal change as disallowing personal exemptions for tax year 2018. Later that summer, the state passed a tax reform package that included language that explicitly disallows state personal exemptions when the federal exemption is zero. That change alone reduced the decline in income tax liability to 1.9 percent (figure 1, step 2).

New York changed its itemized deduction schedule in 2018 to mitigate the effects of the $10,000 annual federal cap on state and local tax (SALT) deductions.

Utah also responded to the TCJA quickly, perhaps because the elimination of personal exemptions disproportionately affects large families and Utah has the largest average household size of any state. The state decoupled its income tax from the federal personal exemption and passed a child tax credit in July of 2018. The legislature also approved a modest tax cut.

Before Congress passed the TCJA, the District of Columbia had fully conformed to the federal standard deduction and personal exemption for tax year 2018. Since then, the district has not revised its conformity laws. However, it has expanded the earned income tax credit and is debating a plan to introduce a permanent child tax credit, which would alleviate the loss of personal exemptions for families with multiple children.

Colorado continues to use federal taxable income to calculate state taxable income. By doing so, the state implicitly accepted all the provisions of the TCJA we studied, as well as its new deduction for pass-through business income that also reduces state tax collections.

Conformity with the federal tax code has real benefits for both taxpayers and states. But states need to be aware that major changes to federal law like the TCJA can have big implications for state coffers and constituents.