Capitalism produces a dizzying array of products and, in the process, generates an enormous amount of wealth. But capitalism creates a problem in that the gains from economic activity have become increasingly concentrated in a sliver of the population. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, half of the population had seen little increase in real wages for decades.

In a new paper in the National Tax Journal, I describe a straightforward solution to capitalism’s failure to equitably distribute the gains from economic growth. The main feature of this proposed solution is a large universal wage subsidy. It would operate as a refundable tax credit that increases in size as the economy grows—guaranteeing that the benefits of capitalism are broadly shared.

In the main version of my proposal, someone earning wages of $15,000 per year would receive $25,000 when combined with the wage credit. Someone with $50,000 in wages would earn $60,000 including the credit.

All in, after accounting for new taxes to pay for the credits, after-tax income would rise for about 100 million low- and middle-income households.

This universal earned income tax credit (UEITC) would match earnings up to a maximum amount. One option for the UEITC includes a 100 percent credit on earnings up to $10,000 plus a $2,500 fully refundable child tax credit (CTC).

The second version of the proposed UEITC adds a form of universal basic income (UBI) such as the one championed by Democratic presidential contender Andrew Yang. This version combines a 50 percent tax credit on earnings up to $14,000 plus a fully refundable annual cash grant of $2,000 per person (adults and children) that would provide meaningful assistance for those who do not or cannot work.

The UEITC is different from the current Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) in two main ways. First, the UEITC and UBI would be available to all, not just those with low incomes. And the net amount of support would be much larger for low-income households, especially those without children.

Universality makes the proposal more expensive than targeted alternatives such as the EITC, but it’s worth the cost. People would be less likely to see the UEITC as welfare because everyone with earnings would be eligible, much as with Social Security. And because the UEITC depends only on an individual’s earnings, it would be much simpler for the IRS to administer than the current EITC, which is based on earnings, household income, and the presence of a qualifying child. The UEITC also would eliminate current-law EITC marriage penalties, which can be quite large for low-income working couples.

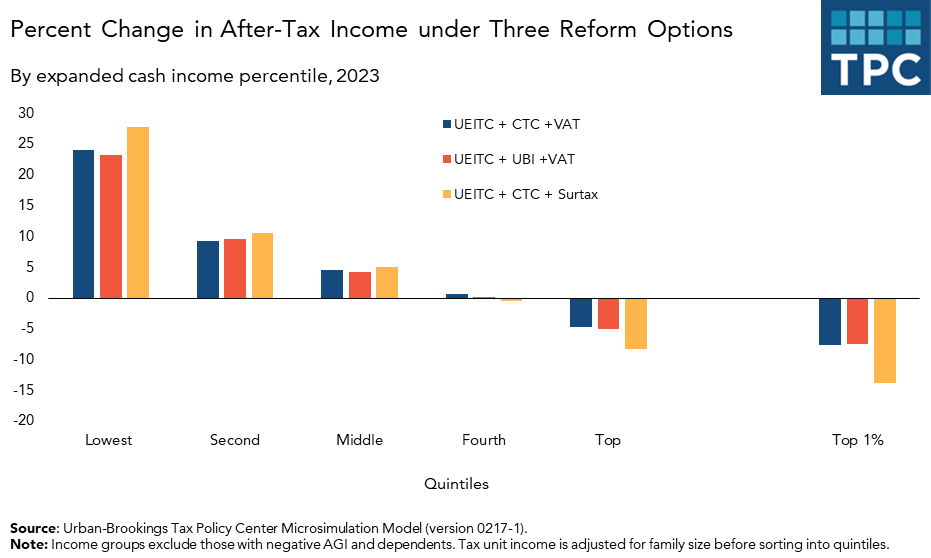

The distribution of who receives a net tax benefit and who pays more depends on how the new credits are financed. For instance, the UEITC could be funded with an 11 percent value-add tax (VAT) or a 12 percent surtax based on taxable income. Even when paired with the more regressive VAT, the proposed UEITC options are quite progressive overall. Recall that Social Security is funded with a a regressive wage tax that is capped at about $138,000. Progressive benefits paired with a regressive tax can result in a policy that is quite progressive overall.

And the UEITC proposal would be much more progressive than Social Security. Low- and middle-income workers would receive far more in tax credits each year than they would pay in additional taxes. In 2023, when fully phased in, the UEITC proposals would cut average tax bills for people making less than $172,500. The net benefit for the lowest income 20 percent of households would average between about $3,800 and $4,500 (23.2 to 27.8 percent of after-tax income), depending on the option. Middle income households would come out ahead by an average of $2,600 to $3,100 (4.2 to 5.1 percent of after-tax income). High-income people would pay more because the burden of the funding source – whether the VAT or the surtax – both increase with income. The highest income 20 percent would pay an average tax increase of $12,000 to $22,000 (4.7 to 8.0 percent of after-tax income). The top one percent would pay an average of $128,000 to $235,000 more, or 7.5 to 13.8 percent of their after-tax income).

Distribution tables may understate the well-being of credit recipients because they don’t account for behavioral responses. Some individuals would respond to the UEITC by entering the work force or working more hours, thus raising their annual incomes and increasing their credit amounts. Over the long run, these individuals would develop job skills that would increase their productivity and wages. Raising the income of low-income parents also benefits their children, who would do better in school, stay healthier, and have higher lifetime incomes. The UEITC would not discourage marriage. And encouraging more noncustodial parents to work in the above-ground economy could reduce incarceration rates and increase the likelihood that those parents pay child support. That would allow them to stay connected with their kids, which also boosts child lifetime outcomes, especially for boys.

The UEITC proposals outlined above also could be modified to help support unpaid caregivers, seniors, and those in worker training programs. The plan would be especially important if increased use of technology limits future cash wages for less skilled workers. As my TPC colleague Nikki Airi recently discussed the pandemic is likely to lead to even more mechanization and downward pressure on wages.

President-elect Biden whispered after the passage of the Affordable Care Act that it was a “big *** deal.” The UEITC could be a big deal too, finally guaranteeing that the economy worked for all, not just those at the top.