For years, tax reformers have advocated reducing marginal tax rates, broadening the tax base, and eliminating provisions that provide special benefits to select forms of investment and consumption and select groups of taxpayers. They claimed this would promote fairness, simplicity, and efficiency. For example, in introducing the Treasury Department’s tax reform proposals that formed the basis for the 1986 Tax Reform Act, Treasury Secretary Donald Regan included among goals of the proposal “lower marginal tax rates, reduced interference with private economic decisions, simplicity, and equal treatment for all sources and uses of income.”

The Office of Management and Budget defines tax expenditures as “revenue losses attributable to provisions of the Federal tax laws which allow a special exclusion, exemption, or deduction from gross income or which provide a special credit, a preferential rate of tax, or a deferral of tax liability.” This definition suggests that how a tax bill affects tax expenditures is one way to gauge how much it meets tax reformers’ goals. Based on reported Treasury estimates of tax expenditures, I calculated that the Tax Reform Act of 1986 reduced tax expenditures from about 8 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 1985 to about 5.5 percent of GDP in 1990. The reduction in tax expenditures came in roughly equal measure from two sources: the elimination and modification of specific tax breaks (for example, the investment tax credit, accelerated depreciation, and special rates for income from capital gains) and lower marginal rates, which reduced the benefit of many of the retained preferences (such as most itemized deductions and excluding from income tax employer contributions for health insurance benefits).

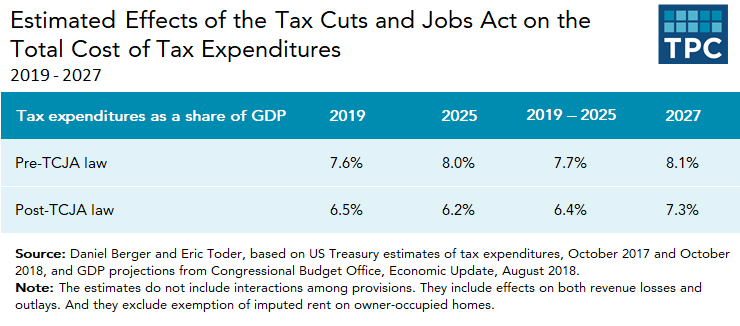

A recent paper I coauthored with my former colleague Daniel Berger finds that the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) also reduced tax expenditures but by a much smaller share of GDP than the 1986 act. Comparing Treasury tax expenditure projections before and after TCJA, we calculate that projected tax expenditures between fiscal years 2019 and 2025 declined from 7.7 percent of GDP before TCJA to 6.4 percent of GDP after TCJA (Figure 1). In 2027, after most of the individual tax provisions expire, projected tax expenditures declined from 8.1 percent of GDP before TCJA to 7.3 percent of GDP after TCJA.

The largest reductions in tax expenditures between 2019 and 2025 were for five provisions: deductibility of nonbusiness state and local taxes ($1.188 trillion), the preferential treatment of active foreign-source income of controlled foreign corporations ($740 billion), the deductibility of mortgage interest on owner-occupied homes ($424 billion), the exclusion of employer contributions for medical insurance premiums and medical care ($361 billion), and the deductibility of charitable contributions ($171 billion). These were offset in part by increases in some existing tax expenditures and the enactment of some new ones. The largest tax expenditure increases were for the expansion of the child credit ($506 billion), the new 20-percent deduction for income from pass-through businesses ($454 billion), and bonus depreciation ($295 billion).

As in 1986, reduced tax expenditures reflect both explicit cuts in tax expenditures and indirect effects on their costs of other provisions. The biggest explicit cut was the $10,000 cap on the deduction for nonbusiness state and local income, sales, and property taxes. The other major tax expenditure declines mostly reflect other provisions in the tax law. The cut in the state and local tax deduction, the increase in the standard deduction, and the decline in marginal tax rates all reduced the cost of deductions for mortgage interest and charitable contributions by reducing the number of taxpayers who itemize and reducing the value of deductions for those who still itemize.

Lower marginal rates also reduced the value of the health insurance exclusion. TCJA changed preferences for corporate foreign-source income from deferral of profits accrued in foreign affiliates to exemption of some of those profits and a reduced rate on others. But the main source of the decline in the cost of tax expenditures for foreign-source income was the lower corporate income tax rate.

Changes in tax expenditures are a rough way of gauging reform, but tax reform and tax expenditure reduction are not the same thing. Some tax expenditures promote worthy goals that society may wish to encourage, either through tax offsets or direct spending. And while shifting subsidies from the tax code to direct spending may improve transparency in measuring the size of government and make the tax system simpler, overall costs of compliance and administration may be lower with a tax break than a spending program.

Finally, tax expenditure cuts do not always reflect budgetary savings. For example, increasing the standard deduction and lower marginal rates reduce measured tax expenditures but also reduce revenue.

The TCJA did reduce the net cost of tax expenditures. But its combination of cuts and increases in tax preferences did not reflect the traditional tax reform paradigm of broadening the base and lowering rates to reduce how much the tax system interferes with private economic decisions.

A version of this blog post was originally posted as part of the AEI blog series, “Trump’s tax reform happened, now what?"