Imagine a husband or wife near retirement age. Their tax rates go up. What do they do? I’ve published a new study, along with Kevin Pierce of the IRS and my Tax Policy Center colleagues John Iselin and Philip Stallworth, that finds wives, or spouses with lower-lifetime earnings (whether husband or wife), are more likely to be nudged into retirement by tax changes than their husbands, or spouses with higher lifetime earnings. But only in some cases: wives and lower-earning spouses more strongly responded to higher tax rates and stopped working if their spouse was also not working.

To study this question, we used data derived from a panel of anonymized tax returns filed between 1999 and 2010 of married couples where at least one spouse was age 50 or older. The responses are small in any given year: We estimate that a 10 percentage point increase in effective tax rates increases the probability of wives and lower-earning spouses (whether husband or wife) quitting by less than 2 percentage points. In contrast, neither husbands nor those with higher lifetime incomes appear to react to those same tax increases.

While women continue working at an older age than previously, Harvard economist Nicole Maestas has recently shown that wives typically retire earlier in life than their husbands. They do this even though they have longer life expectancies and the returns to additional years of work are higher for married women than married men. One reason for their early retirement is that while women tend to marry older men, couples often retire at the same time.

But because wives have historically earned less than their husbands, we suspected that their early retirement might also be influenced by a subtle feature of the tax code: tax rates are determined by the joint income of a couple, so a person’s tax rate depends on the earnings of the spouse. In a progressive tax system such as ours, this can lead to cases in which the lower earner can actually face both a higher marginal and a higher average tax rate, discouraging secondary earners from staying in the labor force.

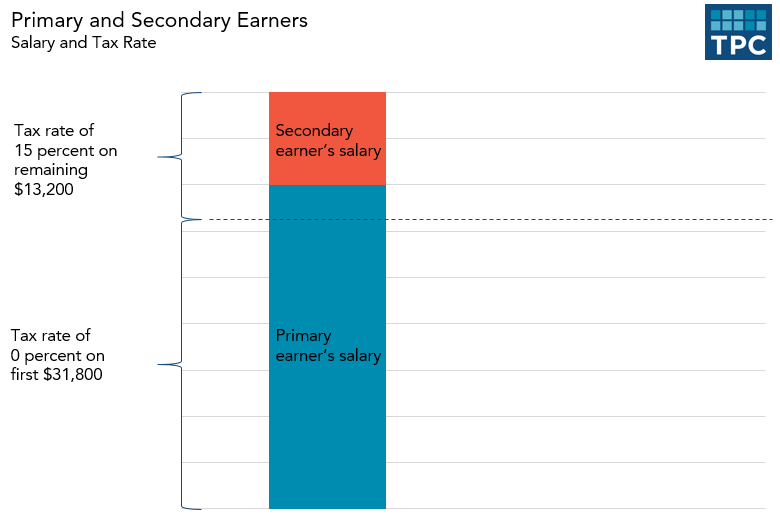

Consider a married couple back in 2010, in which the primary earner had a salary of $35,000 and the secondary earner had a potential salary of $10,000. Assume the couple claimed two personal exemptions, used the standard deduction, and had no other income, deductions, or credits. In 2010, most of this earner’s income would have been untaxed and the remainder would have faced a federal income tax rate of 15 percent. If the secondary earner decides to also work, all of that additional income would be taxed at a flat 15 percent rate (this example is illustrated in Figure below). The primary earner’s average income tax rate is 1.4 percent, while the secondary earner’s average income tax rate is 15 percent.

Traditionally, research on the effect of taxes on work decisions separately examines the responses of husbands and wives. But over the past few decades, women have entered the labor force in ever-larger numbers. Their earnings have increased and they now are the primary earner in more than one in three marriages. Because the tax code can discourage secondary earners rather than wives, it is important to investigate how taxes can affect their retirement decisions, rather than focusing on the effect on wives. In our work, we considered the reaction of secondary earners in a given year, but also the reaction of spouses who have lower incomes over the long run.

We found that taxes affect retirement decisions, but not the way we originally thought. When both members of a couple work, tax rates didn’t seem to affect retirement decisions. Once the primary earner of a couple retires, higher tax rates encourage the remaining worker to follow suit. Our results are consistent with Maestas’s, but we show that taxes can also contribute to early retirement decisions. In addition, the effect isn’t limited to wives; those with lower-lifetime earnings are affected too. Hopefully, future research on taxation and labor supply decisions will focus more on the relative earnings of each member of a couple and stop measuring the effects based solely on each member’s sex.