Next week, voters in our township will decide whether to renew a share of our property tax that funds school repairs, renovations, and construction. Homeowners have been paying this share since 2004, and its proceeds go into what Michigan calls a “sinking fund,” basically a savings account to tap for non-routine expenses.

These funds pay for building renovations, systems repair and replacement, and, if renewed next week, safety, security, or technology. The district stands to lose $2.5 million in 2018 if voters don’t renew the current 0.7165 property tax rate that is devoted to the sinking fund. The owner of a home assessed at $300,000 pays about $215 a year. Without sinking fund revenue, the school district would need to tap its general operating fund to repair or renovate schools.

Our township’s homeowners could vote to renew the current rate, or they could give themselves a little tax relief. Consider that only about 27 percent of our township's households have school-age children. Will others choose to pay a property tax that gives them few direct benefits, but offers indirect benefits like higher property values, improved quality of life, and increased attractiveness to businesses and house-hunting families?

The upcoming vote has me thinking about how and why our property tax dollars fund public education. It’s a tricky thing, asking taxpayers to pay for something they don’t feel they use every day. After all, some see education as a public good that serves the overall economy and community (or that served their family in the past). But others… don’t. That tension exists in my tiny township. And the issue of school financing has generated national headlines over the past few months as a half dozen red states debate the trade-off between recent tax cuts and adequately funding public education.

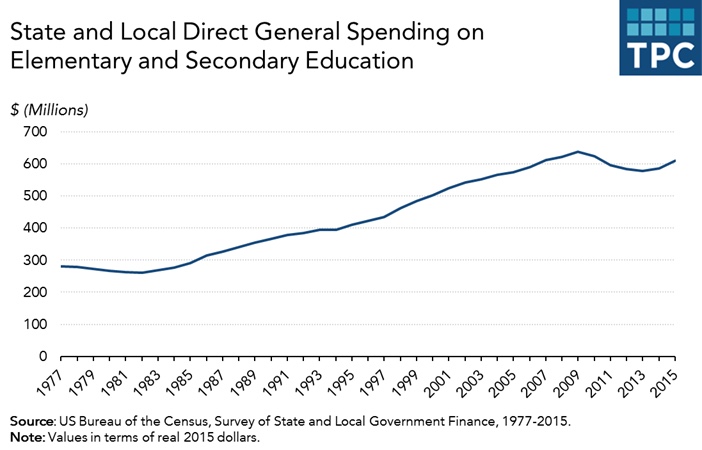

For state and local governments, public education has been the single largest use of direct general spending in every year since 1977, consistently accounting for over 20 percent of all direct general expenditures. Spending on education as a share of total spending has declined a bit over the past 40 years, from 26 percent in 1977 to 22 percent in 2015. But aggregate education spending in real dollars has trended upward, reaching $611 billion in 2015.

A large share of that amount, more than a third according to the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, comes from local property taxes. And today’s homeowners can thank colonial Massachusetts for introducing the property tax as a major source of education finance in the United States.

Writing for The Atlantic, Alana Semuels explains that the Massachusetts School Law of 1642 first required parents to make sure their children could read and write. The Massachusetts General School Law of 1647 then required every town with at least 50 households to hire a teacher—funded by an annual property tax. With the Massachusetts law as precedent, property taxes became the backbone of public education finance, accounting for well over half of spending on public education by the late 19th century and peaking at 78.8 percent in 1930.

But beginning about fifty years ago, parents and school districts began to challenge in court the fairness of financing schools through local property taxes, since some school districts are property rich and many others are not. States responded with funding equalization formulas across school districts and increased state funding for local schools. The financing trend continued, and education spending rose steadily from the early 1980s until 2008—as you’ll see in this figure my TPC colleague Erin Huffer put together.

Then, after housing values plummeted in the Great Recession, state and local tax revenues took a major hit and some jurisdictions responded by cutting spending. As Center on Budget and Policy Priorities’ Michael Leachman explains, states disproportionately relied on spending cuts, rather than a mix of cuts and revenue measures, to close budget gaps across the board, and for several years school spending didn’t keep up with inflation.

That imbalance isn’t terribly surprising. Tax increases are often politically untenable, especially when states are suffering and then recovering from a recession. And promises of “property tax relief” are music to many gubernatorial candidates’—and homeowners’—ears.

In addition, the share of the US population that is school age is falling, while the percentage over age 65 is growing. TPC’s Kim Rueben and research colleagues Sheila Murray and Carol Rosenberg concluded in 2008 that these demographic changes could lead to reduced political support for schools in the future.

And that may have been the case in many jurisdictions. But look what’s happening now in Republican-leaning states that had been spending less on public education while cutting taxes. Tens of thousands of teachers have walked out of classrooms in West Virginia, Oklahoma, Kentucky, Colorado and now, Arizona, all saying that states cut school spending too deeply in recent years. Just this week a coalition of teachers, parents, and education advocates in Arizona proposed a ballot initiative to raise the income tax rate on the wealthy to help fund K-12 public education, including teacher salaries and general operations.

Back home in our township: Will my neighbors see a benefit in renewing a share of their property tax? I don’t know. But I do know that our voting day, Tuesday, May 8, happens to be Teacher Appreciation Day.

Maybe that’s just a coincidence.

The Tax Hound, publishing the first Wednesday of every month, helps make sense of tax policy for those outside the tax world and connects tax issues to everyday concerns. Need help or have an idea? Post a comment, or send Renu an email.