A year ago, the Supreme Court legalized one of America’s favorite illegal pastimes: sports betting. After decades of only being legal in Nevada, you can now wager on sports in seven states, and sportsbooks will open in five more and the District of Columbia shortly. And while the resulting tax revenue will never be the boon some politicians promised, if done prudently, taxing sports wagers can be a winner for states.

In a new brief, I describe how sports betting became an important state finance issue in 2018, which states allow legal sports gambling (both online and in-person), how they tax it , and how much revenue states stand to gain from these taxes.

Here are three take-aways from the first year:

1. States are still learning how to win at sports betting.

All seven states with operating sportsbooks passed legislation before the Supreme Court decision: Nevada legalized sports gambling in the 1940s (and had an exemption from the federal ban) and six others (Delaware, Mississippi, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and West Virginia) made early bets that the federal law would change. Since the decision, Arkansas, the District of Columbia, Indiana, Iowa, Montana, and Tennessee have approved sports betting. However, all these states are still setting up their sports gambling systems. Indeed, the latter four states approved legislation in just the past few weeks, at the very end of their legislative sessions.

What’s stopping other states from joining the field? Some were slowed by procedural hurdles. For example, Maryland needs to wait for a 2020 ballot initiative. Meanwhile, others face opposition from tribal organizations that fear losing their gambling monopolies or residents who object to all forms of gambling. However, some tribal organizations support sports betting because they see it as a way to get gamblers into their casinos, and gambling opposition ultimately did not stop legislation in several conservative states.

States also are still figuring out tax rates. Advocates for sports gambling emphasize that setting the rates too high may encourage illegal betting and thus depress state tax revenue. A 2017 Oxford Economics study set the “high” tax rate scenario at 15 percent. Yet Delaware, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Tennessee have tax rates at 20 percent or higher. States may alter future sports betting tax rates as more states approve sports betting and compete for gamblers, though.

2. States can collect millions of dollars in tax revenue from legal sports betting, but that tax revenue will always be relatively small and volatile.

This isn’t much of a lesson, given that my colleague Howard Gleckman said as much mere days after the Supreme Court’s decision. However, both the expectations and the resulting backlash are now being blown out of proportion.

Yes, some politicians—including those in the District of Columbia, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, West Virginia—set the tax revenue bar absurdly high despite cautious state revenue projections. As a result, multiple media reports have flagged “underwhelming” tax revenue from sports betting.

That fairly describes the experience in Mississippi and Rhode Island, where tax revenue is well below estimates. Rhode Island demonstrated how fickle the game is when its casinos lost money on sports betting in February because too many New Englanders bet on the Super-Bowl winning Patriots.

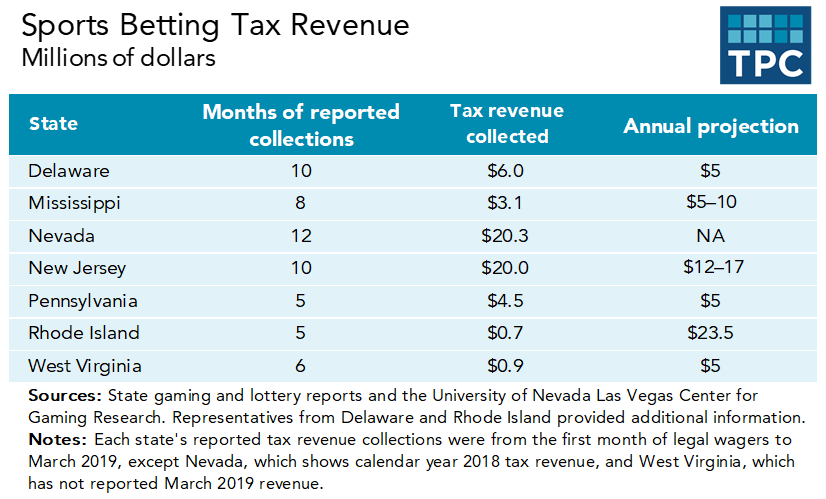

However, sports betting tax revenues are meeting or exceeding expectations in Delaware, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. And while these revenues are well below 1 percent of state general revenue, an extra $20 million, or even $5 million, in your general fund is not nothing.

3. If states want to increase tax revenue from sports betting, they should allow online wagers.

Nevada and New Jersey were the only states that raised $20 million from taxes on sports betting over the past year. They also were the only states that offered widespread online betting.

In fact, New Jersey collected more than three times as much tax revenue from online wagers ($13.8 million) than it did from in-person bets ($4.2 million), even though in-person betting had a two-month head start. (The state collected another $2 million from a special tax on both types of gambling that sends revenue to Atlantic City). In March, the state collected six times more revenue from online operators than from in-person operators.

In search of similar payoffs, the District of Columbia, Indiana, Iowa, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and West Virginia have approved widespread online sports betting, although none of their systems are up and running yet.

Still, it’s important to note that increasing the accessibility of gambling also exacerbates its costs—both personal and societal. Policymakers should fully understand that by offering mobile gambling, they are increasing their state’s revenue because more of their constituents are losing money on sports wagers.

In this game, the states are a bit like the gamblers: It’s fine for them to play as long as they know what they are doing and don’t wager too much on the promise of big returns.