Change can be good, right? Maybe or maybe not. But if you are the Internal Revenue Service, “no change” audits never are good. And, for big corporations, they are becoming more frequent.

A “no change” audit happens when taxpayers substantiate the income, deductions, and credits they claimed on their tax returns. Since the IRS spends money to conduct the audit and receives no additional payments, those audits generate a zero return on investment (ROI) for the government.

Even for taxpayers who prevail, those audits are no picnic. They must spend money (maybe lots) to keep their dough and many individuals may suffer lots of sleepless nights.

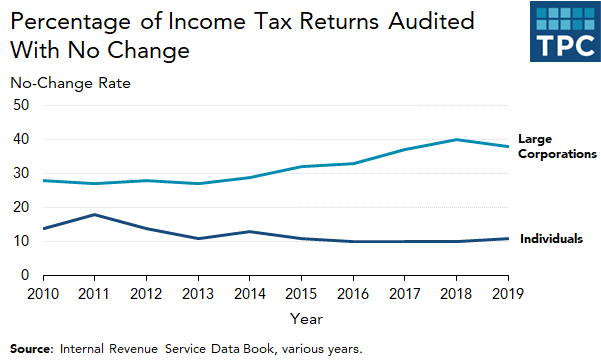

How bad is the problem? It’s bad, with a 38 percent no-change rate, on average, for audits of all large corporations (those with over $10 million in assets) in 2019. It was 16 percent for the very largest—those with over $20 billion in assets.

Compare that to the average no-change rate of 11 percent for individual income taxpayers. Doesn’t seem fair, does it?

The No-Change Rate Anomaly

From 2010 through 2021, the IRS’s budget for tax enforcement—the largest of the IRS’s appropriations accounts—fell by 25 percent, after accounting for inflation.

The conventional wisdom is that when the IRS has less money for enforcement, it goes after the lowest-hanging fruit—the audits that yield a relatively high ROI. But that’s not what the data suggest: Across the board, the no-change rate for large corporations rose from 28 percent in 2010.

That’s consistent with what Jamie McGuire, a Senior Economist at the Joint Committee on Taxation, and I found when we compared the return on audits conducted in 2010 and 2017: Among field audits—the most complicated examinations—the ROI fell from $3.2 to $2.7 for $1 of investment in enforcement activities.

But why the big change in the no-change rate for big business?

I posed that question to a panel of tax experts at the recent Donald C. Lubick Symposium, hosted each year by the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center in honor of Don, who served as a senior tax adviser to Democratic presidents from Kennedy through Obama.

IRS Deputy Commissioner Doug O’Donnell said the IRS surveyed staff to try to determine why the no-change rate rose as enforcement funding declined. Lots of theories but no definitive answer.

Though there’s no consensus within the IRS on why the no-change rate is high, the agency is trying to drive it down by using more data analytics, giving greater weight to risk factors, and updating its detection models.

To outside tax experts, the reason for the high rate of no-change audits is obvious. Sharon Katz-Pearlman, Global Head of Tax Dispute Resolution and Controversy at KMPG; University of North Carolina professor Jeff Hoopes; and University of Georgia professor Erin Towery agreed that the IRS, with its constrained budget and reductions in staff, can’t compete with the big accounting firms and the high-priced law firms that bring sophisticated models and highly-paid tax professionals to the battle.

The result? Firms successfully characterize very aggressive positions as legal tax avoidance and avoid the IRS’s initial charges of illegal tax evasion.

Our panel didn’t talk about lower-income taxpayers. But the IRS’s John Guyton and his co-authors have found that in recent years the IRS denied about 90 percent of disputed earned income tax credits (EITC) after audits. Very often those denials occurred when taxpayers did not respond to requests for more documentation to substantiate their EITC claims. We don’t know, however, whether the EITC claimants didn’t respond because they weren’t compliant, lacked the resources to fight back, feared the IRS, or moved without leaving a forwarding address.

What does this mean for IRS funding?

Amazingly, lawmakers appear ready to boost funding for the perennially unpopular IRS. Just this month, the Biden Administration proposed increasing the IRS’s enforcement budget by $900 million over three years, largely for oversight of the wealthy and corporations.

Representative Ro Khanna (D-CA) has introduced the “Stop CHEATERS Act” that would add $100 billion in additional funding over a decade, with 70 percent going to enforcement. Khanna would set explicit targets for audit rates of the richest taxpayers and the biggest corporations.

The outside experts at the Lubick event applauded more money for the IRS but questioned audit targets. Instead, they agreed the IRS should have more flexibility to determine how to best hire and train examiners and to develop more sophisticated models to catch up with the tools used by corporate tax advisers.

Or simply put, this isn’t just about increasing audits. It’s about increasing productive audits and lowering that no-change rate.