The $10,000 annual limit on the state and local tax (SALT) deduction was one of the most contentious provisions of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA). Since the day it was enacted, lawmakers from the most affected jurisdictions have sought to repeal the provision, which they insist unfairly burdens taxpayers in high-tax states such as New York, Maryland, and California. This week, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) proposed scrapping the cap for two years.

However, merely repealing the cap would add about $76 billion to the federal budget deficit in 2020 and primarily benefit high-income households.

In a new report, the Tax Policy Center analyzes the revenue, distributional, and incentive effects of five ways to replace the SALT deduction cap. Four of the options would impose broad limits on itemized deductions. The fifth would raise individual income tax rates in the four highest tax brackets. The options analyzed are:

- Reduce all itemized deductions by 35 percent (haircut)

- Limit total itemized deductions to $84,000 for married taxpayers filing a joint return and $42,000 for other taxpayers (dollar cap)

- Limit the tax benefit from all itemized deductions to 2 percent of Adjusted Gross Income (AGI limit)

- Limit the tax rate that applies to all itemized deductions to 14 percent (tax rate limit)

- Increase each of the top four income tax rates by four percentage points (raise top rates)

All are designed to generate about the same revenue as the $10,000 limit on the SALT deduction in 2020. Note that our estimates are based on an economic forecast that excludes the economic disruption caused by COVID-19 or legislative relief enacted this year.

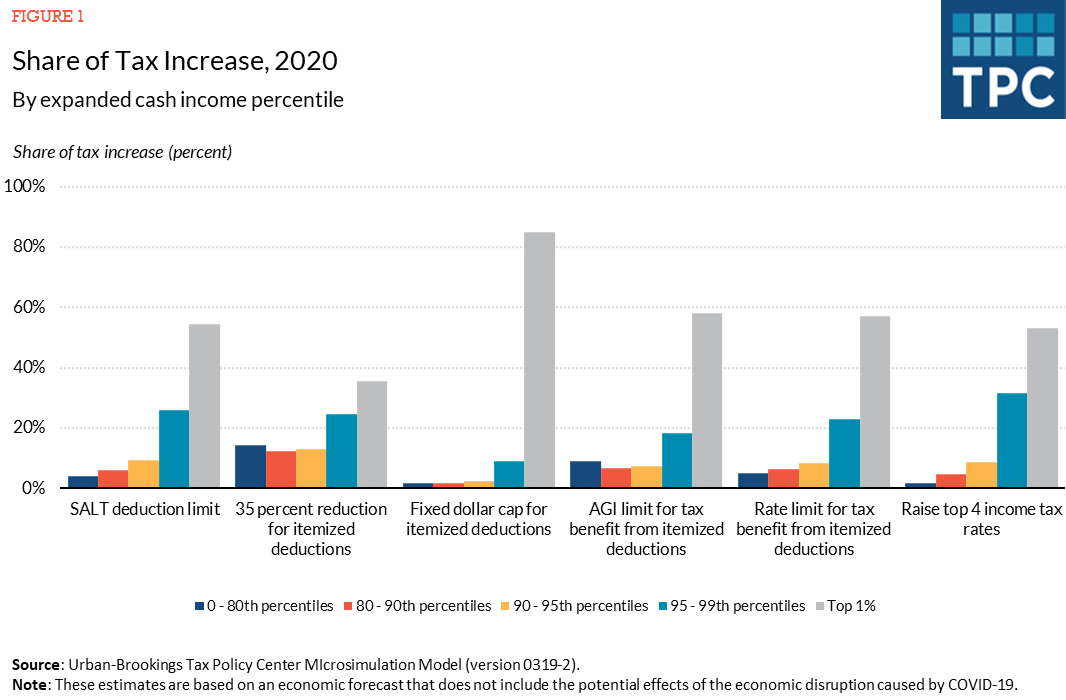

Most of the options would place a similar tax burden on the 20 percent of households with the highest incomes, though each would have somewhat different effects on the very highest income households.

For example, compared to the current $10,000 SALT deduction limit, a fixed dollar cap on all itemized deductions would shift more of the tax burden to the highest-income 1 percent of households. By contrast, a 35 percent haircut for all itemized deductions would transfer some of the tax burden from taxpayers in the top 1 percent to other households.

If Congress raised income tax rates for the top four brackets, the highest income 20 percent of households would pay about 98 percent of the increase, very close to their share under the SALT deduction limit. The income tax rate increase would be less progressive than the itemized deductions dollar cap but would spread the tax increase over a greater number of high-income taxpayers.

The options would have different effects on the marginal tax benefits from itemized deductions. Any of the deduction limits would reduce the value of itemized deductions such as those for home mortgage interest and charitable contributions for some households. The fixed dollar cap and the percentage of AGI limit would nearly eliminate the tax subsidy for additional charitable contributions for taxpayers in the top 1 percent, while the 35 percent haircut would preserve more of the tax incentive for charitable giving for those households. Raising the top marginal tax rates, however, would increase the value of itemized deductions for affected households.

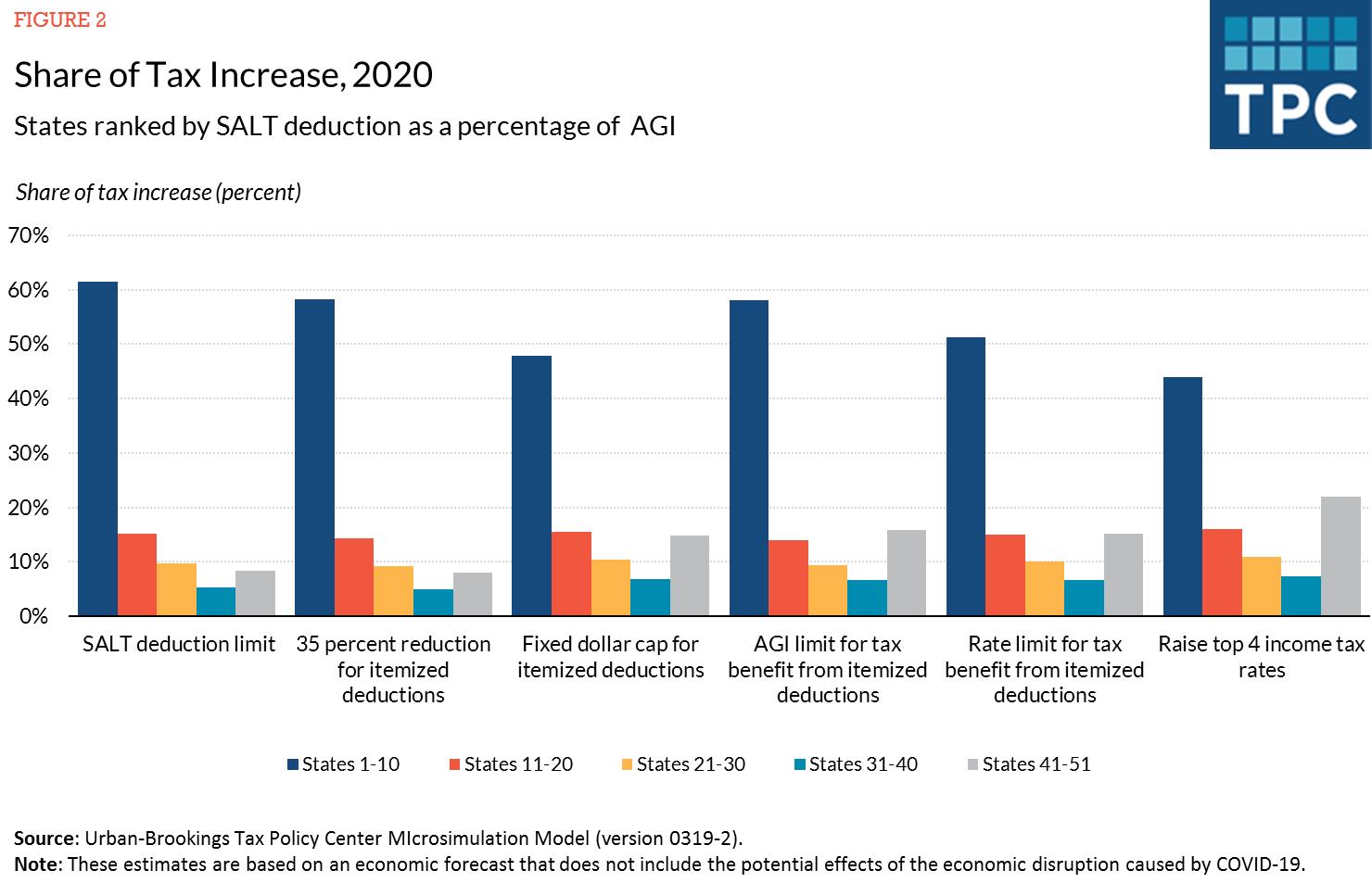

The options also would affect states differently. To show these effects, we rank each of the 50 states and the District of Columbia by their ratio of pre-TCJA SALT deductions to federal AGI in their state, and then divide them into 5 groups. States in the first group, states 1-10, have the largest ratios and can be thought of as “high-tax” states. Details and results for each state are in our supplemental tables.

The options all would shift at least some of the tax burden from residents in higher-tax states to those in lower-tax states, generally by shifting the burden from one group of high-income taxpayers to another.

Taxpayers in high-tax states still would pay about 50 to 60 percent of the tax increase from any of the options to limit deductions. Their share of the tax increase from the 35 percent haircut and the AGI limit would be just below their share of the increase from the SALT deduction limit. However, they’d pay about 44 percent of the tax increase from raising the top four income tax rates because this option would shift the burden to all high-income taxpayers, regardless of their state of residence.

Taxpayers in most other states would pay about the same share of the tax increase from any of the options as their share of the tax increase from the $10,000 SALT deduction limit. But for all options except the 35 percent haircut, taxpayers in the lowest tax states would pay a higher share of the tax increase than their share of the increase from the SALT deduction cap.

Right now, state and local governments are on the front lines of the fight against COVID-19 and in need of financial assistance. Removing the SALT deduction limit would not be the most expeditious way for the federal government to provide fast and flexible support to address state and local fiscal challenges. However, in the longer run, policymakers may revisit the SALT deduction’s role in the fiscal relationship between the federal government and states and localities. When they do, they’ll see that the SALT deduction limit can be replaced in ways that do not add to the federal budget deficit.