On Monday, the U.S. Treasury Department released much-anticipated guidance for the American Recovery Plan’s (ARP) $350 billion in direct state and local aid, including details on how it will implement the law’s restriction on using ARP funds for state tax cuts.

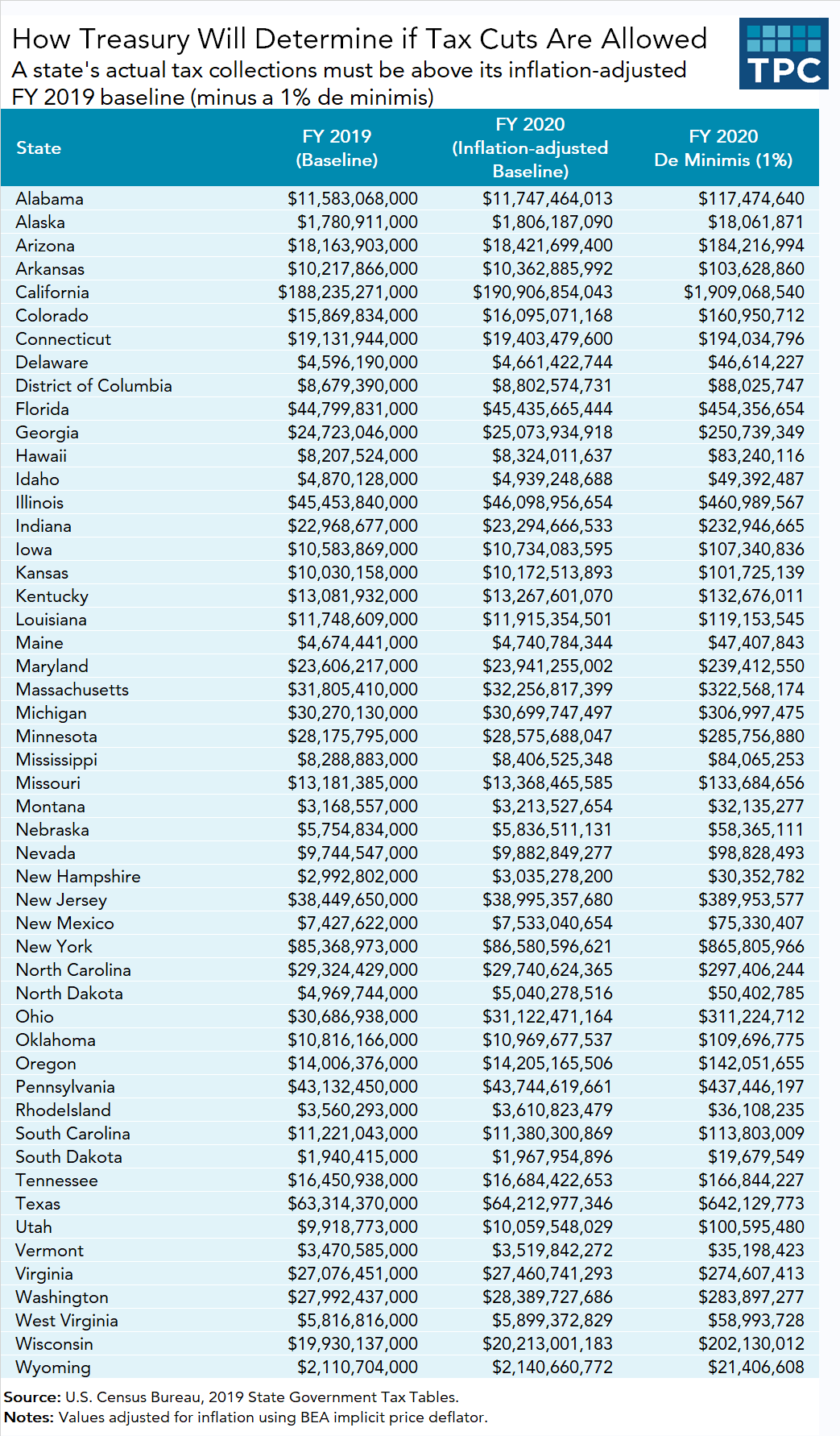

Treasury’s rules give states plenty of flexibility. But there are limits, and until states spend all their ARP funds, they need to focus on two numbers: Their inflation-adjusted fiscal year 2019 tax revenue and 1 percent.

The ARP’s legislative language was fairly broad: States “shall not use [ARP] funds … to either directly or indirectly offset a reduction in net tax revenue … or delay the imposition of any tax or tax increase.” Further, the rule applied to any “change in law, regulation, or administrative interpretation.” And it came with teeth: Treasury will clawback any ARP money used for such tax cuts.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen assured state policymakers that she would not treat this as a blanket ban on state tax cuts, as some Republican state attorneys general asserted when they sued the Biden administration over it, but no one knew how Treasury would thread that needle. The answer: imagine if the pandemic didn’t happen.

Treasury will compare each state’s fiscal year tax revenue during the ARP years (March 2021 to December 2024 or whenever a state exhaust its ARP funds) to its fiscal year 2019 tax revenue—as reported by the Census Bureau and adjusted for inflation. In other words, Treasury will assume that if a state’s tax collections in, say, 2022, are above its real 2019 level, any tax cuts passed that year were paid for with economic growth and not ARP funds.

But, if that state passed significant tax cuts and its 2022 revenue was below its real 2019 baseline, it has a problem. In that case, the state must document how it managed to pass tax cuts without ARP funds. In short, the state needs to show what offsetting taxes were raised or what spending was cut—but critically it cannot make cuts to a department, agency, or authority that used ARP funds. (If you’re so inclined, check out all 151 pages of the interim final rule.)

Treasury also provides states something of a safe harbor. Each state gets a 1 percent de minimis exemption to account for “the inherent challenges and uncertainties that recipient governments face.” Basically, if a state passes an estimated revenue-neutral tax change that turns into a small revenue loser, and that loss pushes the state less than 1 percent below its baseline, that’s okay. The guidance also says states can use the de minimis to pass small tax cuts, with a specific plug for expanding state earned income tax credits (EITC).

To understand how the guidance works let’s look at FY 2020 data. Keep in mind, tax changes in FY 2020 are not affected by the ARP rule, but it’s the most recent year for which we have data. (See the table below for each state’s numbers.)

In FY 2019, Idaho collected $4.87 billion in tax revenue, so its inflation-adjusted baseline for FY 2020 is $4.94 billion. Idaho actually collected $5.28 billion that year, so Idaho could have passed tax cuts and still kept all of its ARP funds because its collections surpassed its baseline.

Meanwhile, Nevada’s FY 2020 inflation-adjusted baseline was $9.88 but it actually collected $9.45 billion that year. Hypothetically, if ARP was in effect and Nevada had passed tax cuts, Nevada would be in danger of losing ARP funding equal to the amount of its tax cuts.

It’s worth noting that Idaho and Nevada’s tax collections diverged in FY 2020 because of the pandemic and not policy. In short, pandemic winners (like Idaho) will have a far easier time passing tax cuts than pandemic losers (like Nevada). But to Treasury that’s a feature not a bug: If a state desperately needs federal help, its ARP dollars better be going toward spending.

Or look at actual tax cuts that fall under the ARP rules. In late March 2021, Georgia increased its standard deductions at an expected cost of $140 million. That’s a tax cut but it’s lower than Georgia’s de minimis ($250 million in FY 2020 and likely higher in FY 2021) so it’s okay. In contrast, West Virginia flirted with $150 million in tax cuts (or more) earlier this year—way above its de minimis ($58 million in FY 2020). Those efforts failed, but if they had succeeded, West Virginia could have lost out on some of its ARP funds.

Treasury’s rules also make exceptions certain tax cuts. Tax cuts resulting from federal-state tax conformity are perfectly fine. For example, the ARP increased the federal EITC for filers without children, and if a state loses revenue because its state EITC conforms with the federal EITC, that won’t count against its tax cut total. States may also refill unemployment insurance trust funds and thus avoid unemployment payroll tax hikes without a penalty.

These details will not stop the GOP lawsuits (because those are as much about politics as policy), but they will give states the guidance they need to craft budgets and, yes, even cut taxes. Think of the ARP as a bar and these rules as the bouncer. All states are allowed in and they can even have a drink too many. But if they overdo it, Treasury reserves the right to cut them off and throw them out.