In a new analysis, the Tax Policy Center’s State and Local Finance Initiative compared governors’ fiscal year (FY) 2022 budget proposals with their state’s enacted FY 2021 budgets and their pre-pandemic executive fiscal plans. The picture is clear: Most states are still a long way from digging out of their COVID-19 budget holes.

The argument that state finances are “better than expected” is often driven by comparisons with the first post-pandemic revenue estimates or states’ most recently enacted budgets, but neither is a good baseline. Those truly catastrophic first estimates were made before we knew that this economic downturn is different from previous slumps: This time, lower-income workers are hurting while high-income workers are thriving. And FY 2021 budgets (passed in calendar year 2020) already included pandemic-related budget cuts that states made to fulfill their balanced budget requirements. Thus, both lower the bar for ostensible fiscal improvement.

Instead, the best way to understand the current state fiscal environment—and its effects on the overall economy—is to examine what states thought the year would look like before the pandemic. With this baseline, the fiscal situation looks worse in more states.

Let’s examine the 23 states that use annual budgets and that we have general fund spending data for both before and after the pandemic. Among these 23 states, eight governors are proposing either FY 2022 spending freezes or cuts compared to what their legislatures enacted for FY 2021. That is, a third of these states and nearly a fifth of all states are clearly worse off because of the pandemic. And this is a geographically and politically diverse group: Alaska, Illinois, Kansas, Massachusetts, Mississippi, New Mexico, New York, and West Virginia.

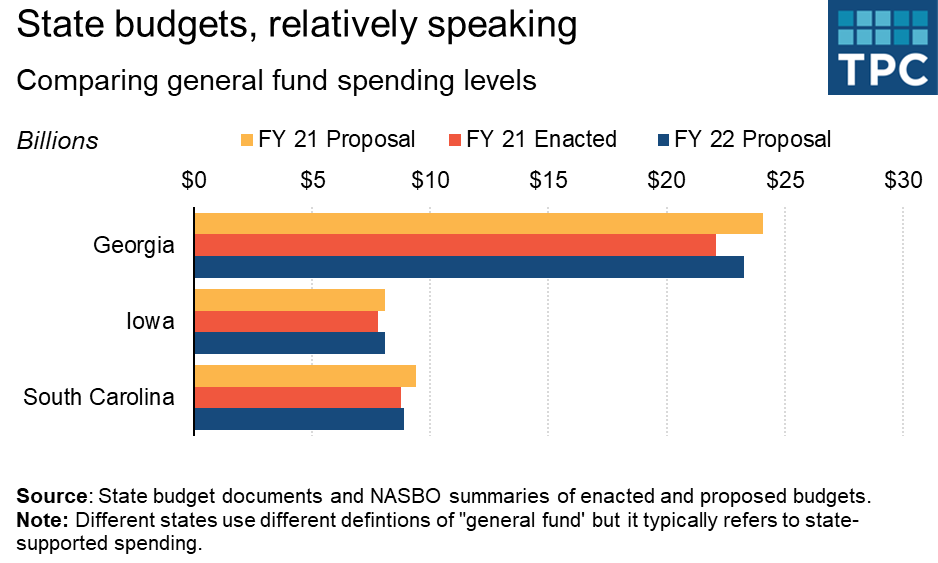

But this does not mean those other 15 states are doing well. In fact, in the governors of Georgia, Iowa, and South Carolina are all proposing more general fund spending in FY 2022 than their legislatures enacted in FY 2021, but less than or equal to what they proposed before the pandemic.

Further, while 11 governors in these 23 states are requesting at least a 3 percent increase in general fund spending compared with their FY 2021 enacted budgets, only six are requesting at least a 3 percent increase compared with the pre-pandemic proposal. For example, while Alabama’s governor would increase general fund spending for FY 2022 by 7 percent over the state’s enacted FY 2021 budget, her fiscal plan is only 2 percent higher than her FY 2021 proposal.

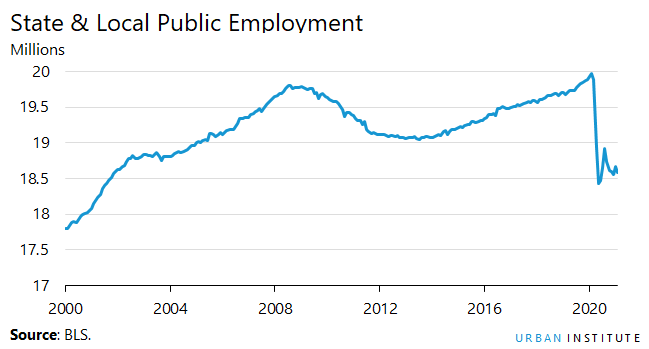

While these numbers can seem abstract, remember that state (and local) governments provide labor-intensive services like education, so much of their spending goes to payroll. The budget cuts and relatively lower spending growth are reflected in the loss of 1.4 million (or 6.8 percent) state and local public employment jobs since January 2020.

Some governors have also canceled planned pay increases for state employees, delayed infrastructure and economic development projects, and punted plans for education improvements. Deferring these initiatives, which governors promoted as economic growth strategies just before the pandemic, would slow the economic recovery.

Of course, the pandemic and economic downturn has played out very differently across different places and populations, so in some states the budget situation is healthier. Utah’s FY 2022 general fund spending proposal is up nearly 5 percent compared with last year’s enacted spending and over 8 percent compared with the governor’s pre-pandemic proposal. The booming stock market and California’s highly progressive income tax system rocketed that state from budget cuts to surpluses almost overnight. South Dakota did not see much change in its spending largely because it was a low-spending state before the pandemic and it remains one now. However, as with state tax revenue collections, the bad overall still far outweighs the good.

And keep in mind that these data only reflect state budgets simply because it is a lot easier to analyze 50 states than thousands of localities. But everything we know about how major cities collect revenue (hotels, parking, events, and restaurants and bars) tells us the situation is probably worse at the local level.

Looking at where states and localities wanted to be in last January and where they ended up this year sheds new light on the $350 billion in unrestricted fiscal support for state and local governments that Congress is close to approving. Getting state and local governments back to where we they were before the pandemic—restoring a year’s worth of lost plans and progress—can help them and the national economic recovery.