In recent years, businesses have been able to fully deduct expenses related to research and development (R&D) in the year the investment was made (often called “expensing”). Since January 2022, though, they have had to spread out (amortize) deductions for R&D expenses over a period of five years, making the tax break less valuable.

Business groups are pushing for the more generous R&D deduction to be reinstated, arguing that the existing law will lower investment in R&D and make the United States less competitive. Although restoring the pre-2022 R&D tax break was included in the American Jobs and Families Act that passed the House Ways & Means Committee last week, the fate of that bill is unclear. However, the preferential treatment of R&D has a long history of bipartisan support, and extending the pre-2022 R&D tax break was part of the Build Back Better Act of 2021.

Is subsidizing R&D even a good idea? One reason to subsidize research is positive spillover effects. Total public benefits from R&D often exceed the private returns a business receives.

The other large-scale federal tax incentive supporting innovation is the research and experimentation (R&E) tax credit. The R&E credit provides an incentive for marginal or additional spending on R&D above a base amount to avoid subsidizing research that would have occurred absent the credit.

The US still contributes a significant fraction of its GDP to R&D, on par with other large, developed economies. However, implied average tax subsidies are low compared to other countries and have declined since the introduction of capitalization. Re-introducing expensing would lower the overall cost of R&D. To spur research spending, Congress could also consider a targeted and slightly more expensive approach by increasing the R&E credit or making it refundable.

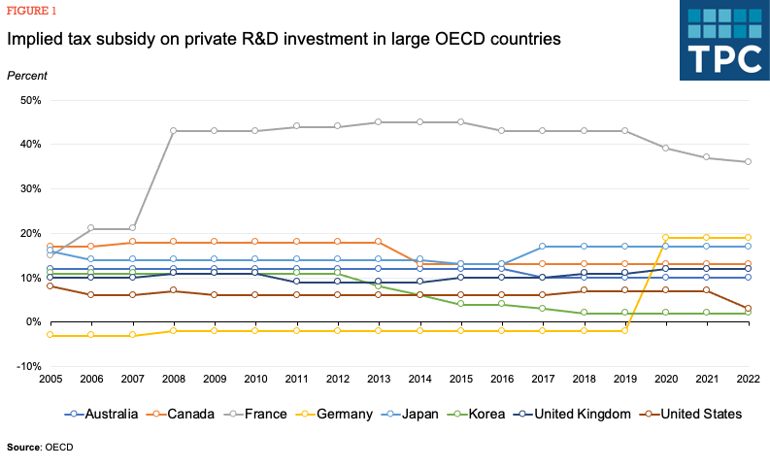

How does the US taxation of R&D compare with other countries?

Other countries support R&D with policies that lower taxable profits derived from intangible property (IP), such as “patent boxes.” IP. Patent boxes can lead to higher investment in R&D as they lower the tax liability on profits from successful innovations. However, they only benefit successful R&D that reaps high enough returns, and they are largely designed to prevent multinational corporations from shifting existing IP to more tax-friendly jurisdictions, or to repatriate existing IP from tax havens.

Just because other countries subsidize R&D heavily does not necessarily imply the US should do the same. Spillovers may happen across countries, in which case the optimal policy in a country may be less than its neighbors. The optimal R&D policy may also depend on other economic factors and investment incentives. However, mapping trends in R&D subsidies between developed economies can provide important insights.

The Organisation for the Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) measures total government spending on both public and private R&D, with the latter including direct support to businesses and tax incentives. In 2019, the latest year available, the United States spent a total of 0.82 percent of its GDP on R&D policies. It ranked 14th out of the 35 OECD members, and the US spent more than the 0.67 percent of GDP average.

However, a large fraction of US government support for R&D is in the public sector, such as research occurring as part of defense spending. Government assistance to private R&D made up only 0.14 percent of US GDP in 2019, mostly through tax subsidies, which amounted to 0.12 percent of GDP, up from 0.07 percent in 2000.

But looking at government spending as a fraction of GDP only tells part of the story. Using data on private R&D spending and tax policies, the OECD estimated the average implied subsidy rate on total R&D spending for a large profitable firm. A 5 percent subsidy implies that a company that spends $1 on R&D must generate 95 cents for the investment to break even.

Before 2022, the implied subsidy rate in the United States was 7 percent. In 2022, it dropped to 3 percent. In the same year, the average implied tax subsidy rate on R&D among OECD countries was slightly over 20 percent, and the US ranked 31st of 36 OECD countries.

While tax subsidies for R&D have decreased in several countries (Australia, Canada, Korea) since 2005, they remain much higher than in the US in all large OECD economies except for Korea (figure 1). However, Korea was also the country with the highest GDP share of direct support to private R&D in 2019.

R&D Tax Break Reforms

Business spending on research must meet more stringent requirements to qualify for the R&E credit than it did for expensing. Using IRS data, we estimate that the average effective rate of the credit (actual R&E credits divided by total qualified research expenditures) is around 6 percent.

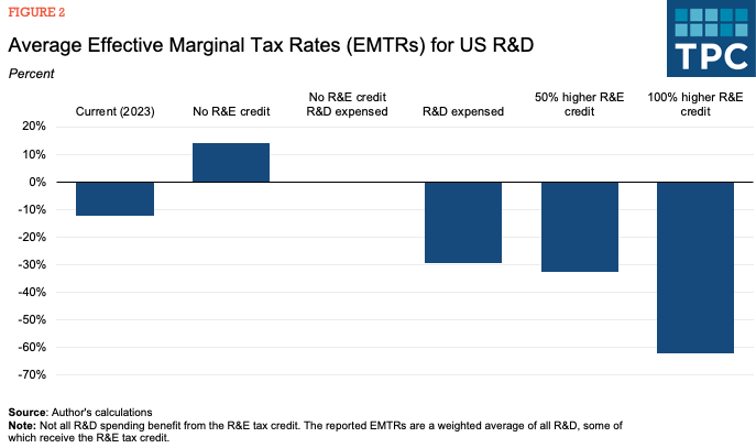

To capture marginal incentives for investment, we estimate the effective marginal tax rate (EMTR) on eligible R&D spending under different scenarios. EMTRs measure the difference between pre-tax and after-tax return for an investment that just breaks even as a percentage of the pre-tax return. A negative EMTR indicates an economic activity is subsidized, and that businesses will invest more than they would have absent taxes.

The current average EMTR for R&D in the US is about -12 percent; it would be about 14 percent absent the R&E tax credit – a 26 percentage point difference. Without tax credits but with R&D expensing, the EMTR is zero, which means the tax system would not impact marginal investment decisions.

Importantly, expensing is worth more in combination with the R&E credit. This is because the impact of both policies combined is larger than each individually added up. Allowing R&D expensing, with the R&E credit left unchanged would bring the average EMTR down to about -29 percent.

Academic research suggests firms respond strongly to the R&E credit. But the credit is costly. The Joint Committee on Taxation estimated the credit cost $13 billion in 2020, compared to slightly less than $3 billion for expensing. The R&D capitalization and amortization requirement was originally expected to raise over $100 billion to help offset the cost of the TCJA, but most of this gain comes from shifting future tax revenues to earlier years.

This suggests increasing the credit by 50 percent would be more expensive than R&D expensing. But, because it focuses on marginal investment, the R&E credit would be more targeted to activities the government wants to encourage and could have a larger impact on total research expenditures.

An important drawback of both the R&E credit and expensing provisions is that only profitable corporations can take advantage of them right away. Businesses can carry forward unused credits, but they must wait to have enough tax liability to use them. Companies that fail never actually benefit from the provisions.

This distorts competition: large and profitable firms can reap the credit and face a lower R&D cost than smaller, growing companies. Making the R&E credit partially or fully refundable would overcome that issue.

Subsidizing R&D through the tax code can create powerful incentives to invest. But the US should rethink the current design of both the R&D deduction and R&E tax credit to better incentivize innovation and ensure these tax breaks work as intended.