As the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) celebrated its two-year anniversary on March 11, some applauded a law that sped an economic recovery while others argued it helped fuel inflation. Specifically, critics pointed to the $350 billion in unrestricted funds for state and local governments as poorly targeted. That debate won’t be settled for years, if ever, but today it’s worth remembering the state and local debates we had a mere decade ago.

During the Great Recession, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act sent state and local governments nearly $290 billion in aid. But unlike the pandemic, there was no second or third recovery bill. As a result, state and local governments spent nearly a decade engaging in fiscal austerity that proved a drag on the national economic recovery.

In contrast, Congress funneled roughly $900 billion to these governments in pandemic-related aid, helping state and local governments respond to the pandemic, replace revenue lost during the downturn, and boost new investments in infrastructure, housing, and economic development.

It may have been flawed. But ARPA aid did help states and localities recover faster and leave them in a better position to face the long-term economic and fiscal challenges on the horizon.

The Great Recession was a disaster for state and local governments

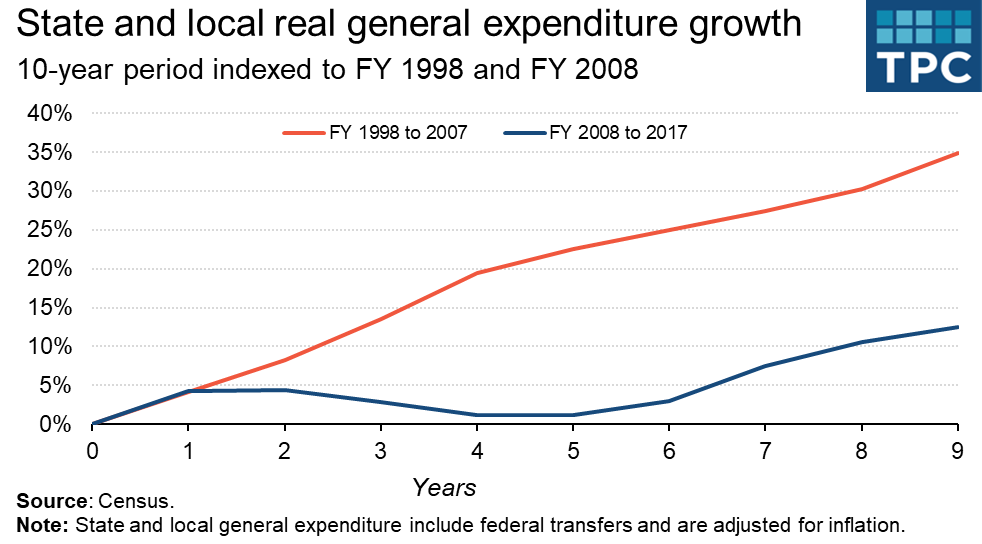

In inflation-adjusted dollars, state and local general expenditures (including federal transfers) grew 4 percent in fiscal year 2009 but then stagnated without sustained support. In fiscal year 2017, a decade after the start of the Great Recession, general expenditures were only 12 percent higher than they were in 2008.

For context, the previous 10-year period saw state and local general expenditures grow 35 percent. While myriad factors contributed to these totals, the simple story is that the federal government did not do enough to jumpstart the economy and assist state and local governments.

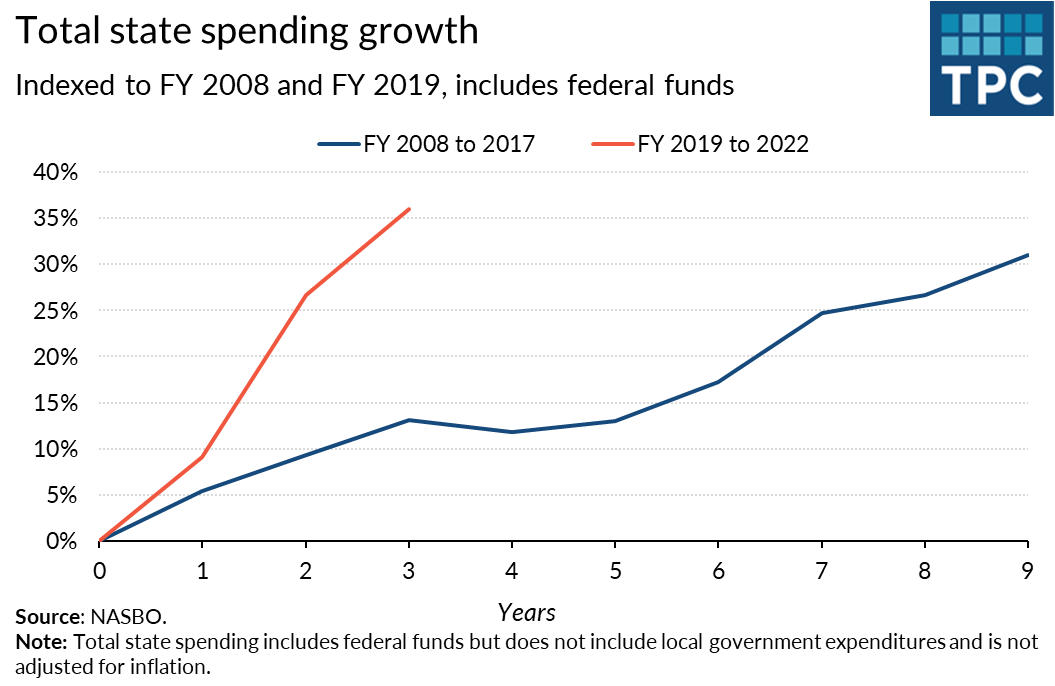

We do not yet have comparable combined state and local expenditure data for the pandemic, but data from the National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO) show a completely different story. Nominal state expenditures (including federal funds) grew more from fiscal year 2019 to 2022 (36 percent) than they did during the entire decade after FY 2008 (31 percent). Notably, fiscal year 2012 remains the only year NASBO has ever recorded a decline in nominal state spending.

And it’s important to remember that state and local spending is not merely a number on a spreadsheet. Most spending equals jobs for people that provide public goods and services to businesses and residents.

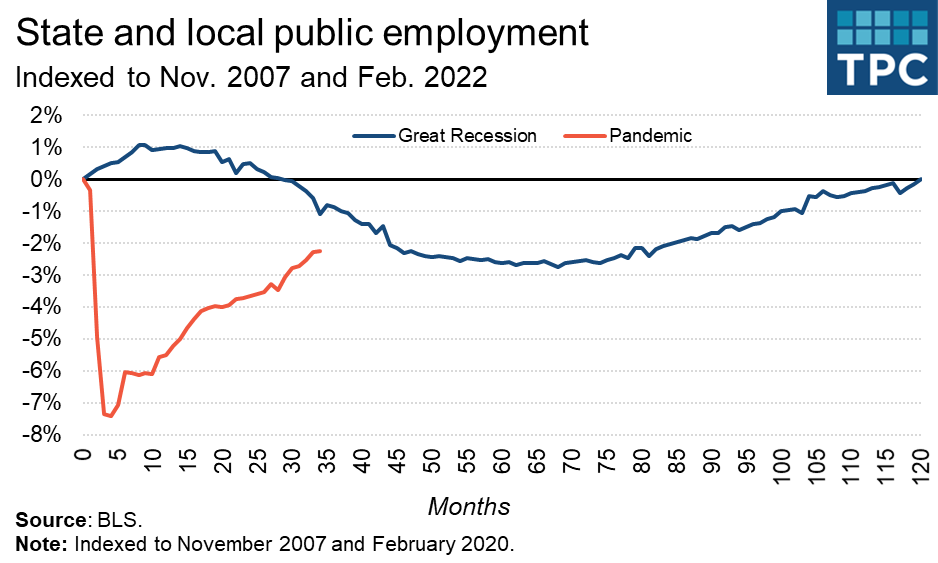

During the Great Recession, state and local employment initially increased but then significantly declined as federal aid ran out and governments cut budgets. It took a full 10 years for state and local government employment to return to its November 2007 levels. This not only harmed government services but contributed to the stubbornly slow national jobs recovery.

While state and local employment has not yet returned to its February 2022 levels, it is on a far better trajectory, and numerous states – from Arkansas to Pennsylvania – are spending money on increased teacher pay and other incentives to compete for and hire government workers.

What about all those state tax cuts?

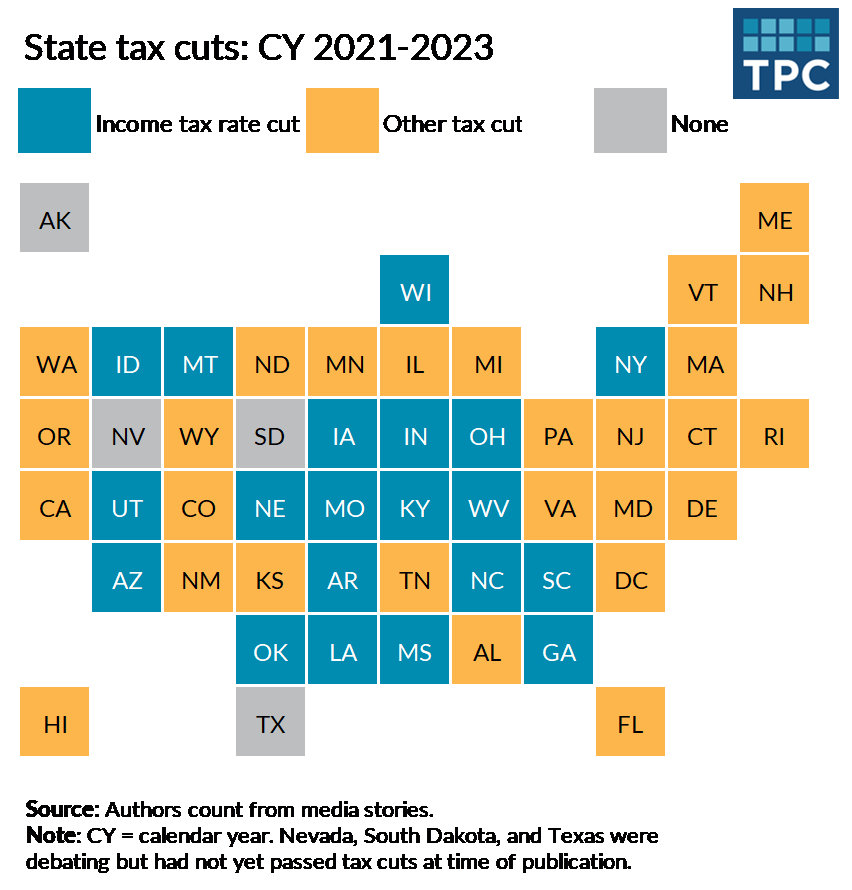

Some hold up the avalanche of state tax cuts since the pandemic as evidence of the ARPA’s excess. Indeed, nearly every state passed a significant tax cut in calendar year 2021, 2022, or the first weeks of 2023. Some of these were permanent individual income tax rate cuts – including sizeable cuts in Arizona, Idaho, Iowa, and Mississippi, but others were one-time tax rebates or smaller, targeted tax credits in line with the broader goals of the ARPA.

Regardless, it’s worth keeping two things in mind when considering these tax cuts. One, many states passed big tax cuts in the wake of the Great Recession in a completely different fiscal environment because tax cuts are a policy choice. Two, it is hard to disentangle the effects of direct federal transfers from the larger national economic recovery.

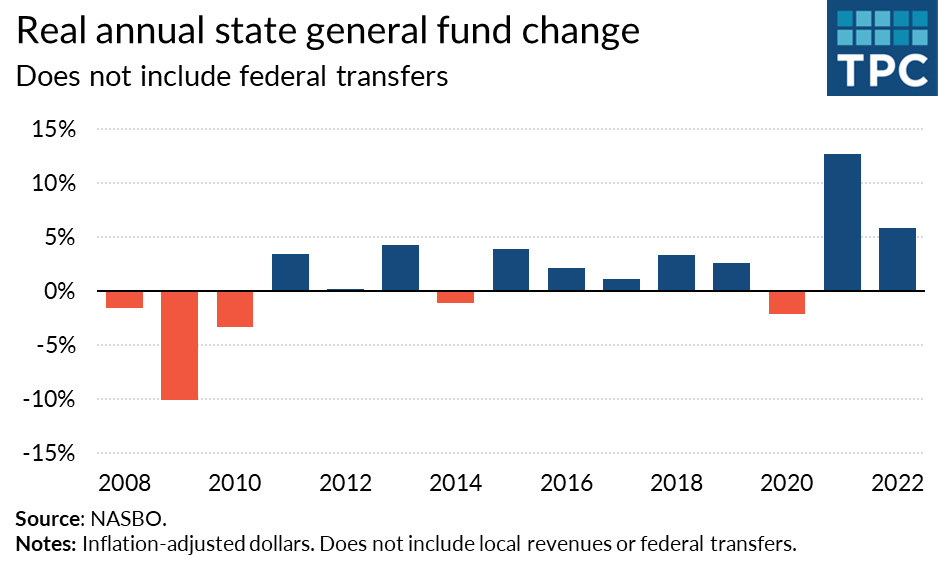

That economic boom is why NASBO reports real, own-source state revenue increased roughly 13 percent in FY 2021 and 6 percent in FY 2022. In sharp contrast, it declined in all three years immediately after the Great Recession. That is, direct federal aid was helpful, but so was unemployment returning to pre-pandemic levels in 34 months (instead of 108 months following the Great Recession) and tax collections filling state tax coffers.

We can still do better next time

There is obviously still room for improvement in our response to an economic crisis. Congress could proactively prepare for the next recession by creating state and local aid mechanisms tied to economic indicators. Such a program could ensure money flows during a dangerous downturn but slows as a recovery builds momentum. It could also ensure aid is primarily delivered to the states that need it most, which is politically challenging when you need 50 senators to immediately pass a plan during a crisis.

Regardless, I’d still argue the ARPA achieved its goals despite the flaws. For the past two years, states have debated tax relief instead of tax increases and how to invest in teachers, transportation, broadband, and health care instead of what projects to cut and who to fire. It’s not perfect but it’s a welcome change from the last time we were here.