Has the $10,000 cap on the state and local tax (SALT) deduction included in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act produced a mass migration from high tax states to low tax states? Despite some recent claims that it has, the data available support the view that “We don’t have any idea.”

When Congress enacted the annual $10,000 federal individual income tax cap on SALT deductions, governors of some high income tax states predicted disaster. For example, New York’s Democratic Governor Cuomo called the cap “an economic civil war” and warned that the “SALT [cap] encourages high-income New Yorkers to move to other states.”

Given the contentiousness of this issue, it’s only natural that researchers would be eager to find answers. But some recent reports may have misinterpreted the available data. Bank of America Global Research issued a report based on IRS data showing taxpayer movements from before the TCJA took effect. Bloomberg Tax used that analysis for a story that it had to withdraw.

The Wall Street Journal [paywall] used estimated data for the first six months of 2018 to attribute migration from California to Nevada to the TCJA. The problems: Decisions to relocate between states often take months to execute, and even then, six months of data is not sufficient to show a trend. And the Journal report failed to acknowledge that Californians had been fleeing to Nevada for years before the TCJA, in part to escape high housing prices.

Still, state officials have good reasons to watch migration patterns. The loss of a single very high-income taxpayer can poke a hole in a state budget. For example, in 2016 hedge-fund billionaire David Tepper, New Jersey’s richest resident, moved his residency to no-income tax Florida, leaving the Garden State’s legislative budget office worried about losing substantial tax revenue. Last fall Donald Trump announced he was moving out of New York, also to Florida.

Are these trends or anecdotes?

Are these merely high-profile anecdotes or evidence of a trend? We won’t know until we see the post-TCJA 2018 tax data—which we expect the IRS to release next December.

We do know that California, Connecticut, Maryland, New Jersey, and New York--states with the highest SALT deduction as a share of total AGI in 2017--were already losing tax-filers between tax years 2013 and 2017, long before the SALT cap was enacted into law.

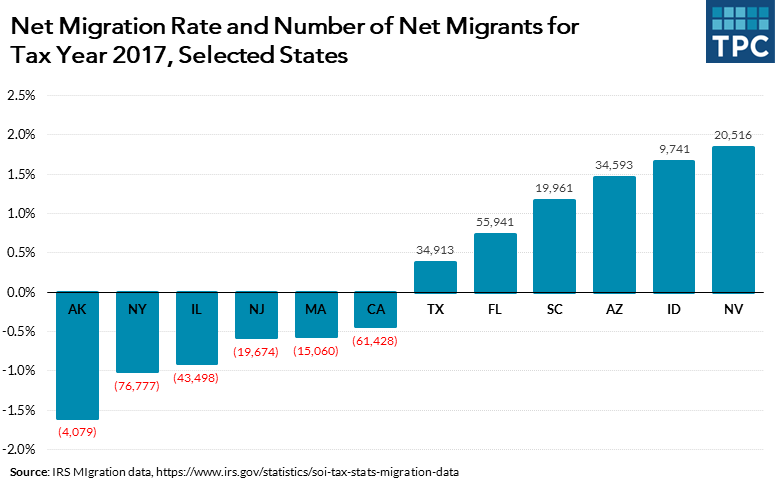

And our data show that high-SALT states of California, Connecticut, Illinois, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New York lost the largest number of taxpayers between tax years 2016 and 2017. But this is a measure of numbers of tax filer-migrants, not their share of a state’s total tax filers, so large population states may top this list merely due to their size. For instance, New York lost on net nearly 77,000 tax-filers during the period, more than any other state. But the state with the largest outmigration rate as a share of total taxpayers was Alaska, a state with no personal income tax or general sales tax. Obviously, tax liability is not the only reason people move.

At the same time, large states without income taxes, such as Florida and Texas, gained the largest number of tax-filers from 2016-2017. As a share of total tax filers, no-income tax Nevada had the highest rate of new migrants. But the top five also included Idaho and South Carolina, both of which have relatively high income tax rates.

People also migrate between high-SALT states: New Yorkers decamp for California in droves, for example. But often, people simply move to neighboring states. New Yorkers often move to Connecticut or New Jersey, both high-tax states. And this indicates that migration is a complex decision, where taxes may play a part, but probably not the decisive role.

Why do people move?

We know that factors such as job opportunities, retirement, and lifestyle drive migration, as a recent Moody’s report [paywall] indicates. Self-reported data collected by the United Van Lines indicate that job opportunities are the primary reason people move.

About half of all states have suffered a net loss of tax-filers in recent years. But it’s too soon to tell if the SALT cap is driving this migration.