At a recent forum on infrastructure, Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden and former candidates Pete Buttigieg, Amy Klobuchar, and Tom Steyer discussed their proposals to bolster spending on roads, bridges, transit and other surface transportation—in part to address threats posed by global climate change.

However, no one said what they’d do about the dwindling federal Highway Trust Fund (HTF). That’s too bad, because the HTF is a key part of how we fund our national transportation infrastructure system, including public transit programs.

The Highway Trust Fund

The HTF gets its revenues primarily from federal taxes on gasoline and diesel fuels, but fuel taxes are not generating adequate revenues to meet transportation needs. People are driving more than before, but the average fuel efficiency of their cars is also rising. Meanwhile, federal motor fuel tax rates have been stuck at 18.4 cents per gallon for gasoline and 24.4 cents per gallon for diesel since 1993. If the federal gas tax had kept pace with inflation, it would be 33 cents per gallon today. Both facts mean that the revenue streams from these taxes are able to support less infrastucture investment than in the past.

But Congress continues to appropriate money for transportation projects. The result: HTF funds will be insufficient to cover planned spending starting in 2021. At that point, Congress will likely transfer general revenues to the HTF, as it has done many times since 2008.

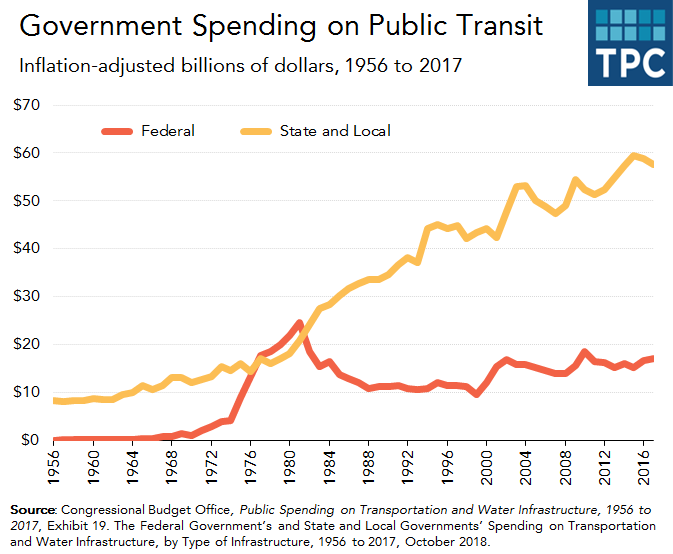

Weaker dedicated revenues for transportation not only shorts bridges and highways, it also cuts federal assistance for local rail and bus services.

Funding Public Transit

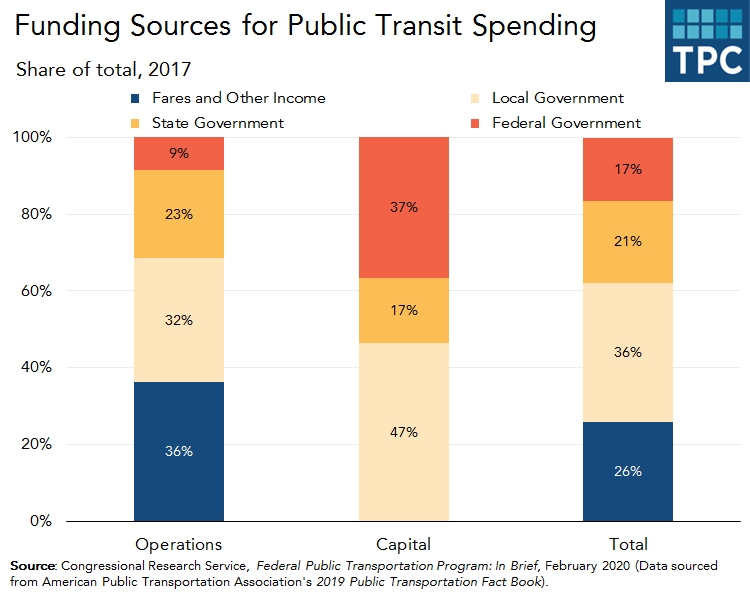

Public transit ridership has grown since the 1990s. Despite a decline in recent years, nearly 10 billion trips or more were taken on public transit each year since 2005. More ridership means more money from fares, but user fares only cover about a quarter of all transit costs.

Most of the rest—a growing share, as federal funding remains flat in real terms—comes from state and local governments.

If the federal government desired to increase its share of transit funding, using revenue generated by an increase in the taxes on gasoline and diesel fuel is a possible source.

The problem is that relatively few voters back a gas tax hike. A multi-year, data-rich national survey by the Mineta Transportation Institute provides interesting insights into public opinion about gas taxes and public transit.

Most respondents overestimated how much they pay in gas taxes, but about 36 percent still supported raising the federal gas tax in 2017. That’s far less than half, but it has trended upward from 23 percent in 2010. Phasing in an increase over five years or earmarking revenues for road maintenance made a prospective hike seem much more popular (58 percent). But overall, respondents preferred cutting other government spending to fund transportation over raising fares or the gas tax.

More than two-thirds of respondents said some gas tax revenues should be spent on public transit. Not surprisingly, those who took transit recently or had transit services nearby were most likely to support that approach.

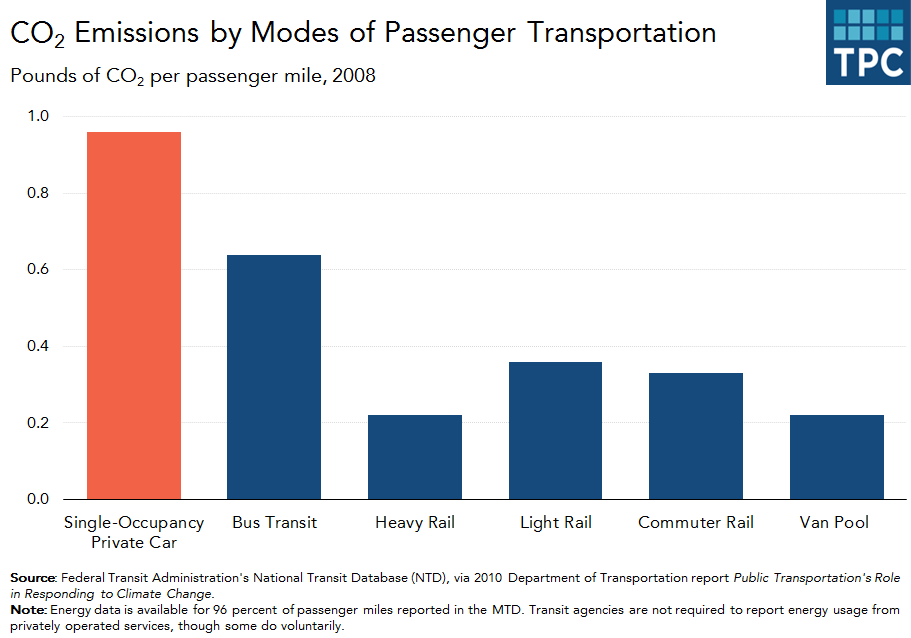

Carbon emissions and transit needs

There is a two-pronged environmental argument for using federal gasoline and diesel tax revenue to fund public transit. First, taxing motor fuels increases the implicit price of carbon, reducing usage and CO2 emissions. Second, directing the revenue to public transit subsidizes an environmentally-friendly alternative to driving. According to the Department of Transportation, all forms of public transit produce fewer greenhouse gas emissions per passenger mile than private vehicles. Furthermore, the total amount of real estate devoted to cars, in terms of both highways and parking lots, raises serious questions of land-use efficiency. The Mineta survey showed that using gas tax revenue to fight global warming and air pollution makes a gas tax hike more popular among respondents.

There is also an economic equity argument to raising fuel taxes for public transit. Motor fuels taxes impose a relatively greater burden on lower-income households than on those with higher-incomes. But using more fuel tax revenues for public transit systems provides a relatively higher benefit to lower-income Americans. These households are more likely to regularly use public transit, commute more than 90 minutes to work, and be negatively affected when local transit options are disrupted by maintenance or budget cuts. Moreover, lack of transportation options can stifle employment and inhibit economic mobility over generations.

Infrastructure often comes up as a topic of discussion among legislators, but there hasn’t been much to show for it in terms of additional dedicated funding. Rising carbon emissions and reliance on public transit will be important features of future debates about the fate of the Highway Trust Fund and infrastructure spending.