Inflation last year reached its highest level in the United States since 1981. As a result, the IRS announced the largest inflation adjustment for individual taxes in decades: 7.1 percent for tax year 2023.

To help people understand where inflation-related tax adjustments might be headed in 2024, I authored a new brief explaining why the inflation adjustment was enacted, how it works, and how the change from using so-called headline consumer price index (CPI) to chained CPI has affected inflation adjustments.

Parts of the tax code were indexed for inflation during the early 1980s, when annual inflation peaked at 13 percent. This led to worries about “bracket creep,” as incomes increased to match inflation but tax brackets, deductions, and exemption amounts were set at fixed dollar levels. For example, in December 1981 the 30 percent bracket for a single taxpayer began at $15,000, the same as in January 1979, even though inflation was more than 37 percent during that time. So, pay increases that kept up with inflation often resulted in taxpayers facing higher marginal tax rates and larger tax bills. All of this meant that federal revenue increased without Congress having to explicitly vote for tax increases. For this reason, inflation was known as a “hidden tax”. The Economic Recovery and Tax Act of 1981, passed in August of that year, addressed the problem by adjusting tax provisions using headline CPI, otherwise known as the CPI-U.

In the mid-1990’s some feared the opposite problem: that tax provisions were being over-indexed, rather than unindexed. If true, it would mean that federal revenues were lower than they should have been. Economists at the Bureau of Labor Statistics published several articles suggesting that headline CPI may be overestimating inflation, prompting Congress to form the Boskin Commission. That commission made several recommendations, including that the BLS turn the headline index into a chained index. The chained index more accurately reflects changes in the cost of living because it measures how spending reacts to changes in prices. However, rather than replacing the CPI-U, The BLS created the chained CPI as an additional index.

Since then, policy analysts suggested from time-to-time that portions of the tax code be indexed with the chained CPI rather than the headline CPI. That finally happened in December 2017, with the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. The use of the chained CPI was expected to help pay for revenue reductions elsewhere in the legislation. One of the disadvantages of the chained CPI is that the inflation adjustment must be made using some initial and intermediate values, because when the adjustment is made, all of the final values are not yet available. As I described in a previous blog, the chained CPI typically rises more slowly than the headline CPI, but the recent surge in inflation saw it rise more quickly.

Twice in the last 15 years annual inflation as calculated by the chained CPI was higher than headline CPI. Although there are no data to explore why this happened in 2008, it happened during the pandemic as initial shutdown tanked demand and prices fell. As a result, the inflation adjustment for tax year 2022 would have been smaller if headline CPI had been used for indexing.

While all the causes for the current worldwide burst of inflation aren’t agreed on, one leading suspect in the United States is the large amount of stimulus spending. Meant to counteract the negative economic effects of the pandemic, the spending increased the deficit by over $5 trillion in a two-year period.

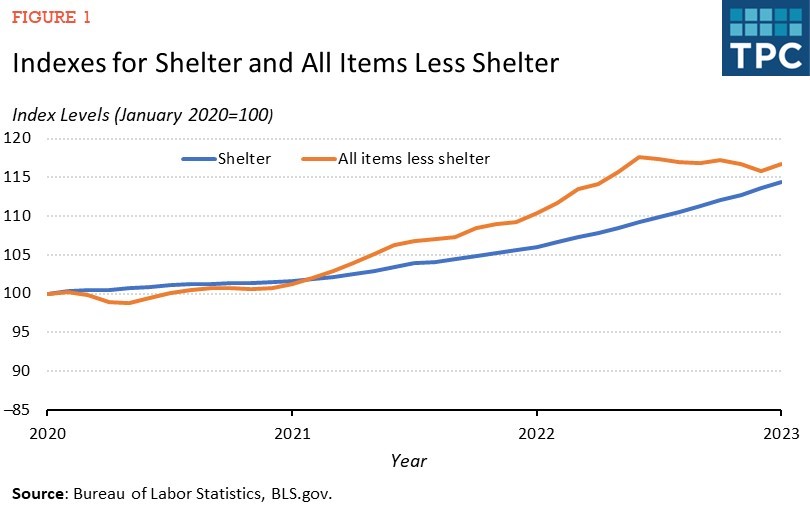

In response to increased inflation, the Federal Reserve Board has raised interest rates significantly. That and stabilizing energy prices has slowed price growth in the CPI. This can be seen in Figure 1 by splitting the CPI market basket into shelter (which is mostly rent of a primary dwelling) and non-shelter services and goods. Other than shelter, since June overall price increases have been moderate.

The recent burst of inflation led to a very large inflation adjustment of individual tax provisions. Whether the adjustment for tax year 2024 is also large will depend on whether inflation over the year is moderate. The most recent CPI release showed an uptick on overall prices. Although it’s too soon to know, if that was an aberration and prices continue to remain stable, then the adjustment will be smaller than that of 2023.