The House Republicans’ proposal for a border-adjustable tax (BAT)—a levy that would apply to imports but not exports—is causing a lot of consternation among retailers who fear that it could jack up prices on foreign goods. Some advocates have argued that importers shouldn’t worry because the dollar would strengthen so much (about 25 percent) that the real after-tax cost of imports would be largely unchanged. Yet, currency markets are telling us that traders think the BAT has little chance of becoming law or that exchange rates will not adjust very quickly.

There are good economic arguments for supporting a well-designed BAT, at least in theory. It would remove taxes from business decisions about where to locate income-producing facilities or other economic activity. The BAT would also remove the incentive to move corporate residence overseas to avoid U.S. corporate income tax (a corporate inversion).

Instead of taxing income generated by production, the BAT would tax consumption. Goods and services would be taxable in the place where they are consumed, regardless of where they are produced. This means that, for example, a car would be subject to the same U.S. tax regardless of where it is assembled or where its parts come from.

However, the BAT faces formidable political hurdles, including strong opposition from retailers and others who think their costs of imported goods will skyrocket.

Here’s the math that so worries them: First, assume a corporate tax rate of 20 percent, which is what the House GOP has proposed. Then, think about a US Mercedes dealer that pays the German manufacturer $50,000 for a car. Without the BAT, the dealer could take a 20 percent deduction from its $50,000 wholesale cost, reducing its after-tax cost to $40,000.

However, under the BAT, its after-tax cost would rise by 25 percent, from $40,000 to $50,000. That $10,000 in additional taxes could easily exceed the dealer’s profit margin. While this feature has importers up in arms, it is also what some politicians find so appealing. As Howard Gleckman noted, they think it would penalize imports and boost exports thereby creating domestic jobs.

This analysis assumes that the dollar cost of imports is fixed. But the value of U.S. currency relative to other currencies is not set in stone. Instead, it responds to supply and demand. And a rise in import prices and parallel decline in export prices would reduce demand for foreign currency and increase demand for dollars. Eventually the value of the dollar would rise by 25 percent. For example, that $50,000 Mercedes costs €47,500 at the current exchange rate of 0.95 euro per dollar. If the value of the dollar appreciated by 25 percent relative to the euro, a dollar would be equivalent to 1.1875 euro. The cost of the car in dollars would fall from $50,000 to $40,000, and the car dealer would be no better or worse off than without the BAT.

However, for reasons that are not well understood, it can take a long time for exchange rates to return to their equilibrium levels after they get out of kilter. A summary of the literature concluded that markets only close 15 percent of the gap between current prices and equilibrium levels per year. Economists Caroline Freund and Joe Gagnon found evidence based on the introduction of VATs, which are also border adjustable, that exchange rates adjust more quickly—with perhaps half of the exchange rate response happening in the first year. But Freund also warned of “lots of complications about the exchange rate adjustment that will happen with BAT that aren't necessarily there with the VAT.” Similarly, Federal Reserve Board chair Janet Yellen cautioned at a House hearing that “It’s very difficult to know just what would happen” to exchange rates.

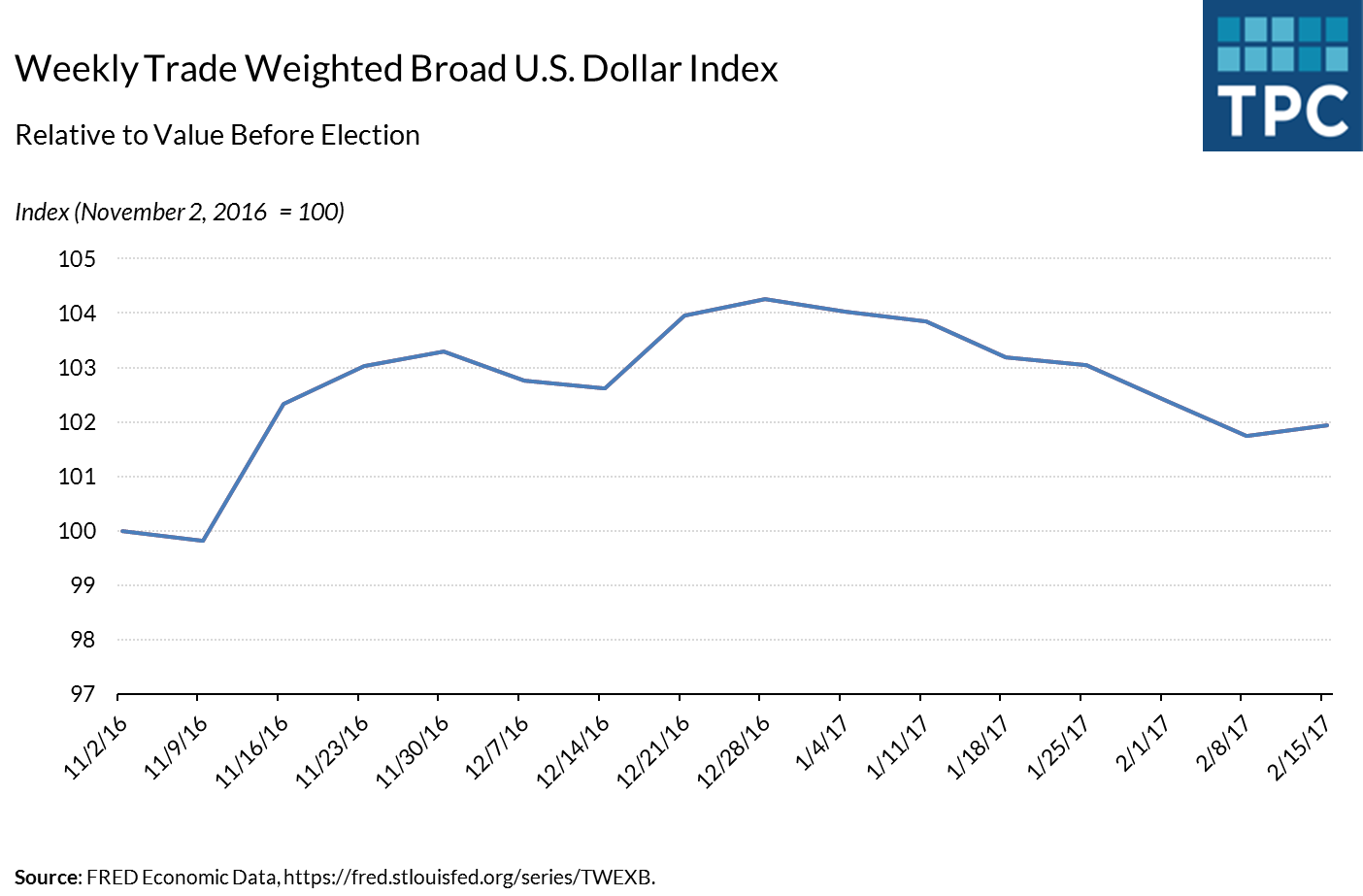

Currency markets may provide a clue to what traders think is going to happen. If they thought that the dollar was going to appreciate significantly in six months, they’d be dumping foreign currency and buying dollars until the price was close to where they expect it to be. If prospects are uncertain, you’d still expect to see a bump in the value of the dollar—just not as much.

Yet, the value of the dollar has barely budged from its pre-election level, when few expected the House GOP plan would become law. Given that other features of the Trump’s fiscal agenda would likely also boost the dollar—in particular, the probability of growing deficits—it is fair to describe the market’s response to this potentially dramatic change as, “meh.”

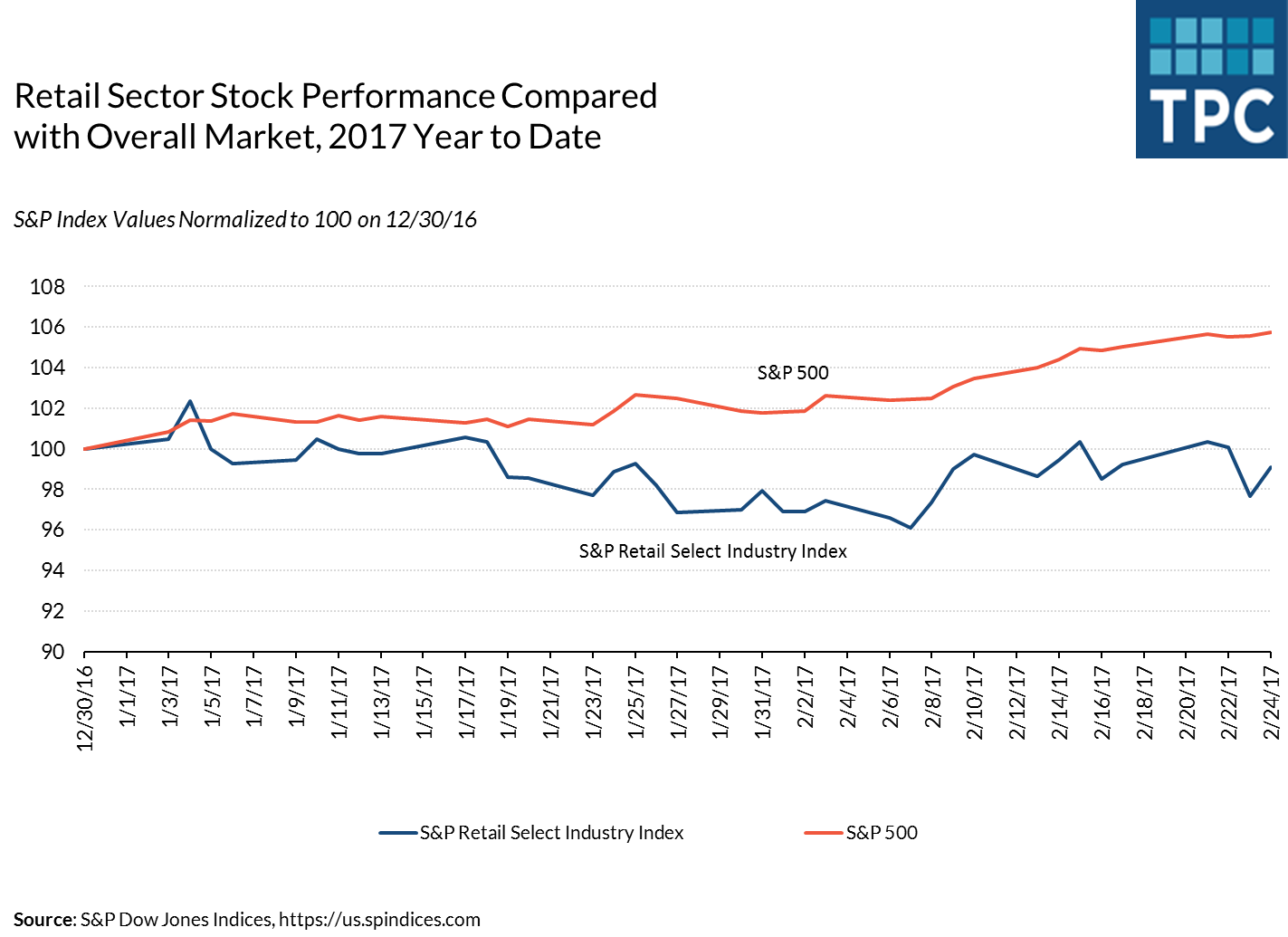

One other bit of suggestive evidence: the S&P index of retailers has significantly underperformed the broader market since January. Lots of things can move equity prices, but one possibility is that markets think the BAT is happening and exchange rates will not fully adjust.

My own view is that a BAT is very unlikely to be enacted because (1) importers hate it, (2) it would entail big annual tax refunds to exporters—in excess of taxes paid—that opponents could portray as “corporate welfare,” and (3) it’s probably illegal under WTO rules. And that might be what currency markets are telling us.