The District of Columbia has created the nation’s most generous state earned income tax credit (EITC) and it will deliver the benefits monthly. The 50 states should take note.

Bigger State EITCs Are Simple, Affordable, and Effective

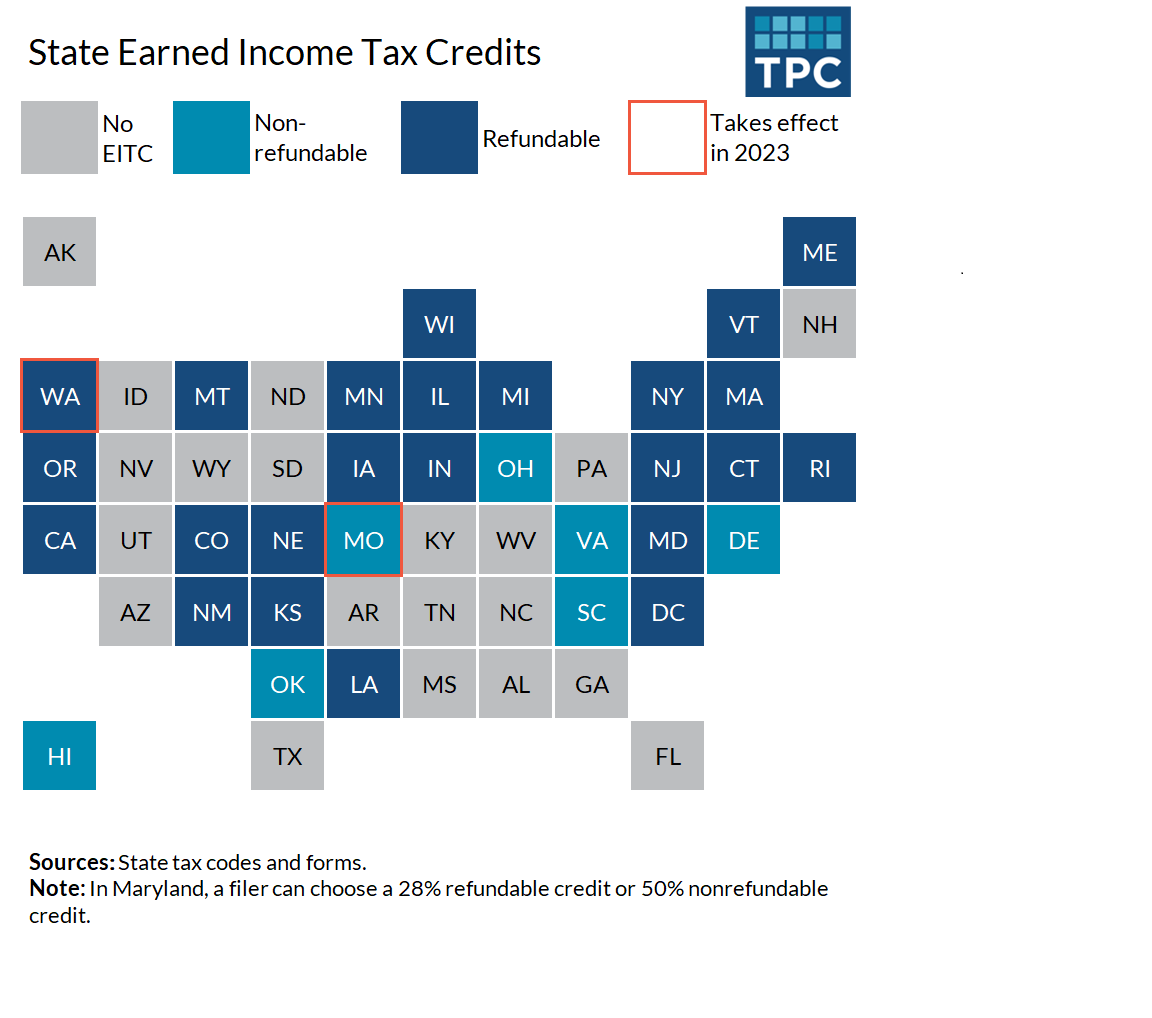

Currently, 28 states and the District of Columbia offer a state EITC. (Missouri and Washington will join the list in 2023.) Most calculate their state credit as a percentage of the federal EITC and thus piggyback on the poverty-fighting design of the federal credit. For example, the District’s EITC is currently 40 percent of the federal credit—tied with New Jersey for the highest match in the nation.

In early August, the DC Council unanimously passed a new budget that bumps that match to 70 percent in tax year 2022 and 100 percent starting in 2026. If the mayor approves the budget (or the DC Council overrides her veto), that District’s generosity will tower above most other states: Of the 19 states that offer an EITC as a simple percentage match of the federal credit and provide a refundable credit, 13 provided matches of less than 20 percent.

This year, the maximum federal EITC for an eligible filer with three or more children is $6,728. The District’s current 40 percent match produces a $2,692 DC EITC, but a 70 percent match would increase the payment to $4,710 and a 100 percent match would double the federal credit for a combined EITC of $13,456.

Getting $6,728 instead of $2,692 from the District is a huge benefit for the filer, but the cost won’t break the District’s budget. The District estimates that raising its match to 100 percent (when compared with the current 40 percent baseline) will reduce tax revenue by roughly $65 million annually—a fraction of the city’s $17.5 billion budget.

A 60-percentage point hike might not be in most states’ plans, but it’s worth underlining the relative affordability of an EITC boost. For example, according to the Tax Policy Center’s state tax model, a 10-percentage-point EITC increase would cost Montana roughly $20 million, Kansas $50 million, Michigan $200 million, and New York State about $400 million—less than 1 percent of each state’s total tax revenue.

That’s important because the Treasury Department says states can cut taxes and use American Rescue Plan (ARP) funds if the tax cut is less than 1 percent of total tax revenue. In fact, Treasury explicitly cited EITC expansion as an allowable tax cut because it directly helps the low-income workers most harmed by the pandemic. More generally, the EITC disproportionally helps women of color.

Additionally, the seven states with nonrefundable credits should make them refundable (which allows filers to receiving credits exceeding tax liability as payments), and the 20 states without a credit should enact them (Washington proved a state without an income tax can do this).

That said, relying on a one-time federal payment to create a permanent state tax cut is risky. Indeed, the District paid for its expansion by raising taxes on high-income residents. But if a state is thinking tax cuts because of the combination of economic growth and ARP dollars then the EITC should be at the top of its list.

But States Should Think Through EITC Reforms

States may want to give more thought to the District’s plan for making EITC benefits monthly, though. Under the new legislation, the District will give an EITC beneficiary 40 percent of her DC credit when she files and the remainder (if it’s more than $1,200) in monthly payments.

That is, the District will delay tax refunds for EITC recipients. No other filers—low- or high income, individual or business— must wait 12 months for their full refund.

The District did this to avoid the messy administrative problems created by advance payments, especially the risk of having to clawback overpayments if a filer’s income or family situation changes during the year. Indeed, the federal government is dealing with this very issue with its advanced child tax credit payments. But delaying refunds still is a significant tradeoff.

Thankfully, there are other, more proven EITC reforms available to states, such as significantly expanding the credit for childless workers (the District was a leader on that, too) and making childless workers ages 18 to 24 and filers without a Social Security number eligible for the state EITC even though both groups are generally ineligible for the federal EITC.

As state policymakers map out a recovery from the pandemic, they should remember there is a simple and cost-effective poverty-fighting tool in their tax policy toolkit. They can tweak it if they like, but all they really have to do is crank up their match as high as possible and let the federal formula do the work.